|

February 14, 2007: Perspective

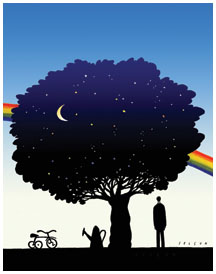

(Illustration by Selçuk Demirel) |

In

God’s antechamber

A relentless illness, viewed through clear eyes

By Charles McPhee ’85

Charles McPhee ’85 hosted a syndicated radio show about dreams, The Dream Doctor, until Oct. 20, 2006, and is the author of Ask the Dream Doctor and Stop Sleeping Through Your Dreams.

The morning of Aug. 20, 2006, I awoke from an unsettling dream; I dreamed that I was blind. In a familiar twist of dream logic, I could also see very plainly that I was blind. In the dream I was having difficulty seeing out of my right eye, so I walked over to a mirror to examine myself better. When I looked, I saw that both my eyes were a green and brown color. They were not full of mucus and covered with cataracts like a person blind from glaucoma; rather, my irises were long vertically, like cats’ eyes. My last thought before I woke was that my vision was definitely impaired.

Moments later, I lay in bed and replayed the sequences of the dream in my mind. I knew from my research and from my long years hosting a nationally syndicated radio program about dreams, The Dream Doctor, that difficulty seeing in dreams is a common metaphor when you’re experiencing difficulty seeing an issue clearly in your waking life. Many people, for example, dream about losing their glasses, or of finding them cracked and damaged, when dealing with challenging events in their waking lives: Should I switch careers? Is my spouse cheating on me? Others may dream of trying to fit contact lenses the size of dinner plates into their eyes. Overwhelmed, these people are trying to see the “big picture,” but they just can’t wrap their eyes around it. My dream’s specificity — the fact that my right eye was impaired, as opposed to my left — was another familiar metaphor, as in, “Can’t get it right,” or, “Wish I knew the right thing to do.” I recalled a caller to my radio show who had dreamed he was hopelessly lost in his car, taking right turn after right turn as he tried to find his way. It turned out that problems in his career were affecting his marriage. He felt lost, and he wanted to know the right way to turn.

Next I concentrated on my feelings, those uneasy emotions that seeing yourself dead or injured in a dream always provoke. I didn’t like seeing myself blind, but I’d learned not to hide from disturbing feelings years ago. Emotional avoidance was a topic I had covered at length in my first book, Stop Sleeping Through Your Dreams. Instead, I held onto the feeling so it wouldn’t run away, until, through insight, it became my friend. This dream wasn’t so hard to understand.

The previous night I had returned from a weeklong holiday on Nantucket Island. But this was a different kind of holiday. The family was flying in, gathering to lend support after learning that my initial diagnosis of Lou Gehrig’s disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), in June, now had been confirmed for the third time by a world-class specialist, Dr. William Graves, at UCLA. I had broken the news to my radio audience that same night, Aug. 3, finally answering listeners’ long speculation about what was happening to my voice. For months I had struggled with recurring hoarseness and the occasional slurring of words when I combined particular consonants. “Is Charles drunk?” concerned listeners would ask my call-screener. “If he is, I know someone who can help.”

With my wife and daughter asleep in their beds, I had stayed up late reading e-mails from well-wishers that had accumulated while I was away. Many shared stories about people who had ALS. “My uncle Bob was diagnosed in June 2003. He died April 2004.” “Cousin Sarah. Diagnosed January 2001. Died July 2002.” “Loving spouse Robert. Diagnosed October 2004. Died November 2005.”

As I read the e-mails, I realized that only two well-wishers knew someone with ALS who was still alive. I also gathered that the median life span after diagnosis, from this sample, was 1.5 years. Lying in bed, thinking about the mail I had read before sleep, I now understood why I had dreamed I was blind. It was still the early stage of my illness, and I felt fabulously healthy. I was swimming and bodysurfing five days a week in the cool ocean waters off southern California. If you saw me on the beach, you would have assumed, correctly, that I was an athlete. My illness was very hard to see — even for me. But the e-mails were a wake-up call. ALS is an unrelentingly aggressive disease.

Anybody with ALS can tell you the date, the time, and what the weather was like on the day he or she was diagnosed. My date was June 23, 2006, at 5 in the afternoon. It was a hot, sunny day without a cloud in the California sky. I was diagnosed by Dr. Yuri Bronstein at the Kaiser Medical Center in Woodland Hills, Calif. For support, I had brought along my radio syndicator, George Oliva III ’77. I remember that I kept waiting for Yuri to get to the treatment part of his explanation. But Yuri sat silent, mostly looking at the floor.

Twenty minutes passed after he delivered the news of my diagnosis — an eternity in the life of a modern doctor. I wondered: Does he just have a bad bedside manner? Is he uninformed about ALS? Eventually Yuri picked up a phone and called a social worker — someone trained in crisis management — to provide me with immediate counseling.

“Have you had thoughts of suicide?” she asked. “Yes,” I replied honestly. I had only been diagnosed for 30 minutes, but my mind had raced quickly forward to ways of killing myself if it all grew too overwhelming. The saddest thought was that my daughter, Celia, all one-and-a-half years of her ebullient self, would not get to grow up with her father — nor I with her.

Five months have passed now since my diagnosis. My voice is much weaker, as my particular type of ALS — bulbar — attacks the motor neurons that feed and control the muscles in my mouth, neck, and shoulders. Speech, intelligible at least, soon will be a thing of the past, as the tongue will grow too thick and dense with lack of coordination to twist and bend itself into the gentle folds needed for elocution. Soon after, it will grow too weak to aid with chewing and swallowing food. Other muscles in the neck required to get food from the back of the mouth to the stomach also will fail. Eventually, as nerve and muscle damage inexorably spread together, breathing will become impossible without a respirator. This is the point when most ALS patients allow their lives to expire.

Despite this grim prognosis, the tidal waves of emotion and panic that

first accompanied my diagnosis have retreated. Today I am buoyed along

in the currents of a quick-moving river; as they say, you’re never

more alive than when you’re standing next to death. I realize I

have entered a new community — the vast legions of people living

with illness, cancer and other bad diagnoses — and I am hardly alone.

Most dramatic is my liberation from the illusion of time — that

there always will be more time to see a friend, to repair a marriage,

to spend with a child, to develop a hobby, or to concentrate on one’s

spiritual life. There will not always be more time, even for those who

are healthy. I have learned that in death’s mirror, the magic and

beauty of life truly are illuminated. My days are rich and full, spent

with family, friends, and colleagues. I am still working, but yesterday

I bought my daughter a training tricycle a few months early. Her long

legs can’t touch the pedals yet, but they will soon. It feels good

not to be blind. ![]()

Charles McPhee ’85 wrote this essay in late October. He currently is undergoing an experimental treatment of his ALS with long-term antibiotics, in an effort to slow its progression.