|

October 10, 2007: Notebook

The Class of 2011 arrives

Freshmen make their mark as Princeton’s biggest, most diverse class

Princeton takes on a Second Life

Whitman ’77: Creating a new ‘icon’

BREAKING GROUND - Near Eastern

studies

A digital look at medieval texts

Freshman receive cheers and applause as they walk through FitzRandolph Gate onto campus during the annual Pre-rade. (Beverly Schaefer) The Class of 2011 Applicants: 18,942* Students admitted: 1,838 (9.7%, including 47 from the waitlist) Students enrolled: 1,246* Yield: 67.8% Students on financial aid: 54% Men: 52.2% Women: 47.8% States represented: 47 (plus Washington, D.C.) Countries represented: 44 U.S. minority students: 37.2%* Varsity athletic prospects: 16.9% Sons/daughters of alumni: 14.7% International students: 11.2%* Entering graduate students Doctoral-degree students: 412 Master’s-degree students: 165 Applicants: 8,776 Students admitted: 13% Men: 61% Women: 39% International students: 40% U.S. minority students: 15% Humanities and social sciences: 50% Sciences and engineering: 45% Architecture: 5% * Denotes record number Sources: Office of Admission; Office of the Dean of the Graduate School. Figures are for the preregistration period. |

The

Class of 2011 arrives

Freshmen make their mark as Princeton’s biggest, most

diverse class

Normally, during the week of orientation before classes start, it’s easy to spot the freshmen. They’re the ones traveling in groups of seven or more, staying 10 feet away from their parents at all times, and — one of the most telltale signs — looking starry-eyed at their new surroundings.

But this year, the older students shared this sense of adjusting to the unknown: Like the incoming Class of 2011, the sophomores, juniors, and seniors also were unacquainted with the Princeton they settled into during the second week of September. With the inauguration of the four-year residential college system and the opening of the 250,000-square-foot Whitman College, the Princeton to which students returned this fall was a different one than they had left in June.

As the biggest, most diverse, and most international class in Princeton’s history, the Class of 2011 represented one of these changes to campus life. Of the 1,246 freshmen, 139 students (11.2 percent of the class) hail from 43 other nations and 463 (37.2 percent) are of minority backgrounds.

Lauren Kustner ’11 looked forward to being a part of such a varied group of individuals. “Being with everyone at once made me realize I was part of a bigger group of people all here to do different things for different reasons, and I’m excited to be part of that,” Kustner said.

In her address to the Class of 2011 at Opening Exercises, President Tilghman celebrated such encounters with things unfamiliar and expressed her hope that the incoming students would find their next four years full of the unexpected.

“The best part of an adventure of learning and discovery is that it often leads to surprises,” she said, pointing to the work of Princeton professors across numerous disciplines whose research had led them to unanticipated conclusions. “We ask you to be open to new ideas, however surprising; to shun the superficial trends of popular culture in favor of careful analysis; and to recognize propaganda, ignorance, and baseless revisionism when you see it. That is the essence of a Princeton education.”

During Freshman Week, a grueling schedule of orientation activities kept the new Tigers running among departmental open houses, faculty panels, placement exams, scavenger hunts, and arch sings, among other events.

Many freshmen saw the start of classes as a welcome relief from this hectic calendar. “I’m excited to have structure in my life again,” said Bianca Mathabane ’11. “With all the events this week, everything was really crazy and frazzled with the things I needed to get done, the things I should go to, and the things I wanted to do for fun.”

At the freshman assembly lecture at McCarter Theatre, molecular biology

professor Bonnie Bassler encouraged students not to fear biology, but

stressed the “fun and mystery” of the field. “Anyone

can do science. People are taught to be afraid of science, that it is

a hard, horrifying thing only a few people can do,” said Bassler.

“Even if you’re an artist or philosopher-writer, I want to

try to convince you that science is equally creative — only instead

of the written word or paint, our medium is nature.” ![]()

By Bianca Bosker ’08

Persis Trilling, the avatar of Educational Technologies Center director Janet Temos ’82 *01, poses in front of the Second Life version of Nassau Hall.

Forseti Svarog (Giff Constable ’94) develops software for the virtual world. (Princeton university on second life: images courtesy Janet Temos ’82 *01; Giff Constable ’94) |

Princeton takes on a Second Life

Reaching the Nassau Hall bell tower has never been so easy. At Princeton’s campus in Second Life, a Web-based virtual world, users navigate with avatars, or digital versions of themselves, that fly with a click of the mouse. Digital visitors can launch from the sidewalk and reach into the recesses of the tower in a matter of seconds. But would-be pranksters likely will be disappointed: In Second Life, as in real life, there is no clapper to steal.

In September, the University launched its Second Life campus, a set of eight contiguous “islands” featuring remarkably accurate re-creations of Nassau Hall, Chancellor Green, and Alexander Hall, as well as a virtual art museum and a “sand- box” space — aptly named Alexander Beach — where users can experiment with Second Life’s construction tools. (For more information, visit etc.princeton.edu/sl.)

Janet Temos ’82 *01 (avatar name: Persis Trilling), director of the Educational Technologies Center (ETC), said the University aims to draw faculty, students, and alumni to the space, but how they will use it remains unclear. The voice-enabled platform could become a virtual classroom or lab, an art exhibition space, or a meeting place. The University also hopes to broadcast real-world events like lectures on video screens in the virtual campus’s amphitheater. One thing virtual Princeton will not be: a red-light district. The islands have a PG rating, Temos said.

Princeton, one of a handful of colleges that have campuses on Second Life, does not plan to use the virtual world for recruiting undergraduates, at least in the near term. Users who are under 18 use a separate teen grid, where traffic is relatively light compared with the regular grid, which is home to about 9 million avatars.

To own real estate in the virtual world, users must buy server space from Second Life’s creator, Linden Research. Educational institutions receive a discounted rate, Temos said, so Princeton paid a total of $6,700 for its eight islands, plus about $1,200 per month for maintenance. ETC employees developed parts of the campus, but the University hired a Second Life freelance architect (avatar name: Scope Cleaver) to complete the most detailed buildings.

Giff Constable ’94 (avatar name: Forseti Svarog), general manager of software for the Electric Sheep Company, said he was excited to see Princeton building a presence in the rapidly growing but “not quite mainstream” world of Second Life.

Virtual worlds, Constable said, offer a real-time, face-to-face connection

that does not necessarily exist on social networking sites like Facebook

and MySpace. “It has the potential to make the world a smaller place,”

he said. ![]()

By B.T. (avatar name: Bach Nikolaidis)

Meg Whitman ’77, lead donor for Whitman College, shares a word with architect Demetri Porphyrios *80 and President Tilghman before the Sept. 27 dedication ceremonies for the 500-student residential college, the largest construction project in the University’s history. Tilghman described the Whitman family’s $30 million gift as “a magnificent contribution transforming not only Princeton’s campus, but its future.” (Frank Wojciechowski) |

Whitman ’77: Creating a new ‘icon’

When Princeton’s board of trustees debated the style of architecture that would be appropriate for a new residential college, Meg Whitman ’77 recalls, it was the young alumni trustees who were the strongest supporters of the collegiate gothic style.

“The reason they were so passionate is the permanence and tradition,” Whitman, the president and CEO of eBay and a former Princeton trustee, said in a Sept. 17 interview with PAW. “They wanted it to be an icon of what Princeton really stood for. It looks like Princeton.”

A $30 million gift to Princeton in 2002 by Whitman and her family became the cornerstone for what would become the largest single construction project in University history. Whitman College, a 500-student residential college built at a cost of $136 million, opened its doors this fall and was dedicated Sept. 27 — the key to an 11 percent expansion in undergraduate enrollment and the launching of the four-year residential college system.

The new college, Whitman said, is “what I envisioned — it’s spectacular.” Asked by architect Demetri Porphyrios *80 if she liked how the college plans had been realized, Whitman said she replied: “I don’t think it could be any better: It’s an A.”

Whitman said she was very involved in the planning of the college’s high-ceilinged dining hall, donated by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar and his wife and named Community Hall in honor of eBay’s community of buyers and sellers. “I spent a lot of time on that dining hall,” she said. Her favorite spot in the college is an octagonal, semiprivate wood-paneled dining room off the main dining hall. “I’d love to have dinner there,” she said.

Whitman said she also pressed for the college to offer as many single rooms as possible and served “as a cheerleader” for Porphyrios.

Whitman, who entered Princeton as a premed student but became an economics major and played squash and lacrosse, said she “loved every minute” of her college experience. “It gave me the chance to experience things I never had a chance to experience, and self-confidence to pursue a full range of options,” she said.

But Princeton today, she said, is “stronger and better,” with more opportunities; it’s bigger and more diverse and much more global. Whitman and her husband, neurosurgeon Griffith Harsh IV, have two sons; both attend Princeton, one as a senior and one as a freshman.

Whitman said she hopes students living in Whitman College “will appreciate the value of community, and to connect with other students in ways they might not otherwise ... to really understand the power of a close-knit community” — a belief, she said, that stems from her experience with those who do business with eBay.

While visitors to Whitman College have been struck by a level of amenities

and architectural details not found at the other residential colleges,

Whitman said that shouldn’t be a concern. “If you put something

in the ground, you have to take a very long view — what will be

necessary 50 to 100 years from now,” she said. “You can’t

build what is the standard for today; you must build a standard for tomorrow.”

![]()

By W.R.O.

(Beverly Schaefer) |

Princeton fans had little to cheer about at the football team’s

32–21 loss to Lehigh Sept. 15, but on the home sideline, one face

was all smiles. The Tiger mascot debuted its new perky, plush-pawed costume

in front of more than 8,600 opening-night spectators. When the athletics

department held an online contest to name the mascot, tradition prevailed.

It will be known, simply, as “the Tiger.” ![]()

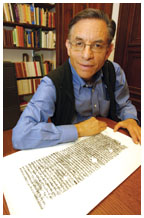

Professor Mark Cohen. (Frank Wojciechowski)

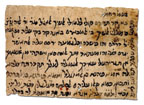

A letter about an unpaid debt, below, and its transcription from the Princeton Geniza Project’s searchable online database, above. Everyday correspondence from the Cairo Geniza provides a window into the lives of medieval Jews and Muslims, according to Courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Library, Cairo Genizah Collection (Halper 358)

|

BREAKING

GROUND - Near Eastern studies

A

digital look at medieval texts

Cairo, in the 11th and 12th centuries, was a comfortable place for Jews, who comprised a significant minority in the city. Though treated as second-class citizens under Islamic rule, Jews lived side by side with Muslims, in relative harmony, and took part in a flourishing economy, according to Mark Cohen, professor of Near Eastern studies. “Jews were heavily invested in international commerce, interacting with people of other faiths,” he says.

Cohen’s assessment is drawn largely from documents found in the Cairo Geniza, a tomb for sacred texts that was discovered at a synagogue in the late 1800s. In addition to holding religious poems and fragments of Torah scrolls, the Cairo Geniza contained thousands of mundane papers from the medieval period — letters, contracts, wills, and other legal documents — preserved in the area’s arid climate. This collection represents a unique window on daily life in Egypt from about 1000 to 1250.

For more than two decades, Cohen and his Princeton colleagues have been working to bring the ancient papers into the digital age. Their work, called the Princeton Geniza Project, has created the world’s only online, searchable-text database of the Cairo Geniza’s historical documents.

The Hebrew word “geniza” refers to both the place and the act of burying worn or damaged sacred papers, a practice that continues today. (The Jewish Theological Seminary Library in New York, Cohen says, has a wastepaper basket labeled “geniza” for discarded photocopies of sacred books.) The medieval Jews of Cairo had a broad definition of sacred. Letters that began with the phrase “in the name of God,” for instance, ended up in the geniza. While Princeton does not hold any of the original documents, the Near Eastern studies department has thousands of photos and annotated transcriptions compiled by one of Cohen’s mentors, the late S.D. Goitein, a prominent geniza scholar who lived in Princeton and worked at the Institute for Advanced Study.

In 1986, Cohen and Abraham Udovitch, a colleague in the Near Eastern studies department, proposed using Goitein’s papers to start a computerized database of geniza documents. IBM and the Near Eastern studies department supported the effort, and in the past 20 years, with help from technology upgrades and recent grants from the Friedberg Genizah Project, the database has grown to include nearly 4,000 documents (at least a quarter of the historical geniza), available online and searchable in Hebrew and Arabic script or English keywords.

The project “reaches out to the world, and not just to the Western world,” says Cohen, who notes that scholars have used geniza documents to study history and culture in the Arab world. Roxani Margariti *02, an assistant professor at Emory University, wrote her Ph.D. dissertation, recently published as a book, about commerce in Aden, a medieval port city in present-day Yemen. Archaeology, literature, and travel accounts shaped her work, but the Cairo Geniza was a “crucial source,” she says, because it provided direct information about trade routes and the region’s economy.

Many of the geniza documents are incomplete, with the tears, holes, and frayed edges that one might expect to find in papers removed from an 800-year-old trash bin. Noting those imperfections on a plain-text Web page is an imperfect science, says Ben Johnston, a database specialist at Princeton’s Office of Information Technology, so the next phase in the Princeton Geniza Project may be to add images of the original documents and enable researchers to flip back and forth between the document and its transcription.

Expanding the database will require time, money, and capable transcribers,

Cohen says, and he is dedicated to finding all three. “The technology

itself is breeding new users,” he says, “because you don’t

have to get on a plane and go to Cambridge [home of the largest collection

of geniza papers]. ... This is an amazing resource, and it’s growing

the field.” ![]()

By B.T.

Taking

the pulse of the humanities

Grafton: Princeton is a bright spot, but humanists are losing

ground nationally

If the image of the scientist in popular culture is that of the absent-minded genius, Professor Anthony Grafton says, humanities professors are often portrayed as pompous, even lecherous, bores.

Grafton, the Henry Putnam University Professor of History, assessed the state of humanities education in America at a retreat last month at the Mountain Lakes House in Princeton that attracted more than 30 faculty members. Delivering the keynote remarks, Grafton cited a loss of the sense that those who teach the humanities have a mission to speak to the general public.

Although the University’s Council of the Humanities has long promoted community across academic disciplines, the retreat was a new initiative by philosophy professor Gideon Rosen, who chairs the council, to bring scholars together off-campus to discuss not only their particular academic specialties, but also their areas of shared interest.

“Lots of people [at Princeton] will say, ‘I’ve been here for 20 years and I know X is a famous historian, but I’ve never met him,’” Rosen explained. “Our hope was that people who are not normally thrown together would be able to talk.”

If their popular image is the bad news for humanists, the good news is that the number of students in the humanities, at Princeton and at other elite private universities, seems to be holding steady. “Humanistic education is very strong at Princeton, so far as I can see,” Grafton said, “thanks to our continued commitment to undergraduate education, the excellent quality of our undergraduates, and our continuing initiatives to attract even more students with interests in the arts. ... We send a disproportionate number of young people off after Princeton to careers in the arts and in humanistic scholarship.”

But at other universities, Grafton and Rosen said, the humanities are losing ground not only to the natural sciences, but to the performing arts. Viewed nationally, Grafton said, “We are genuinely shrinking, and like Alice we are not convinced that three inches high is the best way to be.”

As evidence of the diminished place of humanities education in American society, Grafton pointed out that the creation of the Council of the Humanities in 1953 was reported on the front page of The New York Times, something it is difficult to imagine happening today. The first Gauss Seminar in Criticism, in 1949, drew a number of intellectual luminaries from New York who knew each other’s works and were able to discuss them in a way that also engaged the broader public. “There was a ritual of shared reading,” Grafton said.

But engaging not only the public, but even one’s peers beyond a narrow academic subspecialty, is essential to the creation of a broader humanist, Grafton said. He decried the writing of poetry by those who do not think it important to have first read a lot of poetry, citing Edmund Wilson ’16 as a counter-example. Though Wilson was a wretched novelist, Grafton said, he was a better reviewer of fiction for having tried to write fiction himself.

In addition to Grafton’s introductory talk, the humanists had a chance to learn about each other’s academic disciplines. Professors Leigh Schmidt, chairman of the religion department; Leora Batnitzky, acting director of the Program in Judaic Studies; Stephen F. Teiser, acting director of the Program in East Asian Studies; and Robert Wuthnow, director of the Center for the Study of Religion, led a panel discussion that traced the history of religious education at Princeton and explored its continuing relevance on campus. Linguistics professor Adele Goldberg presented a paper on the existence of universal grammar. And Claudia L. Johnson, chairwoman of the English department, and associate professor Jeff Dolven read and led discussions of several short poems.

The first retreat was a success, Rosen said: “We’ll do this

again next year.” ![]()

By M.F.B.

CHARLES BERRY, a longtime economics professor and creator

of the “Berry ratio,” died of cancer Sept. 2 in Princeton.

He was 77. Berry developed his ratio, which measures profitability by

relating a company’s gross profits to its operating expenses, to

evaluate transfer payments between companies and their subsidiaries. The

tool is used in tax law in the United States and abroad. A member of the

Princeton faculty from 1966 to 1995, Berry also served as an associate

dean of the Woodrow Wilson School and as master of Rockefeller College.

![]()

Princeton’s new CAPITAL CAMPAIGN, which kicks off in November, will seek to raise $1.75 billion by Reunions 2012, officials said last month. Robert Murley ’72, campaign co-chairman, said that more than $500 million has been promised during the “quiet phase” of the campaign. In the Ivy League, Columbia and Cornell each have $4 billion campaigns under way; Yale is seeking $3 billion, Brown $1.4 billion, and Dartmouth $1.3 billion. An analysis of the University’s needs and what donors can be expected to give determined Princeton’s goal, Murley said.

| Division | Percentage of A’s | |

| 2001–04 | 2004–07 | |

| Humanities |

55.5 | 45.9 |

| Social sciences

|

43.3 | 37.6 |

| Natural sciences

|

37.2 | 35.7 |

| Engineering | 50.2 | 42.1 |

Three years into the University’s new GRADING POLICY,

the faculty has “demonstrated conclusively” that a concerted

effort can lower inflated grades, according to the Faculty Committee on

Grading. In the three academic years from 2004–07, 40.6 percent

of course grades were A’s, compared to 47 percent in 2001–04.

In April 2004 the faculty approved “grading expectations”

that A’s should account for less than 35 percent of the grades in

undergraduate coursework and less than 55 percent in junior and senior

independent work. In comparing the three-year averages, the committee

reported that all but three departments had made “significant”

progress, and those three — all in the natural sciences —

already had been grading in line with the policy. Some departments still

need to grade more rigorously, the committee said. Rob Biederman ’08,

president of the Undergraduate Student Government, said that while grade

deflation has had some positive effects, skepticism continues among students.

“It remains a monumental task to constantly reinforce the now-substantial

difference between a Harvard and a Princeton GPA,” he said. ![]()