Features - January 26, 2000

Dangerous Words

Professor of Bioethics Peter Singer and his views on life and death have

challenged the university and the world at large

Faculty appointments seldom create an uproar. But when Princeton hired

Australian philosopher Peter Singer away from Monash University in Melbourne

and appointed him as DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at the university's Center

for Human Values, his controversial views on infant euthanasia became more

widely known in this country, and the press, some alumni, and certain special-interest

groups reacted loudly. Disabled rights and pro-life activists protested

his first day of class. And the university has taken precautions to protect

his safety, routinely stationing security guards at his public speeches

on campus and putting packages with unfamiliar return addresses through

an airport-style scanner before he opens them.

Faculty appointments seldom create an uproar. But when Princeton hired

Australian philosopher Peter Singer away from Monash University in Melbourne

and appointed him as DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at the university's Center

for Human Values, his controversial views on infant euthanasia became more

widely known in this country, and the press, some alumni, and certain special-interest

groups reacted loudly. Disabled rights and pro-life activists protested

his first day of class. And the university has taken precautions to protect

his safety, routinely stationing security guards at his public speeches

on campus and putting packages with unfamiliar return addresses through

an airport-style scanner before he opens them.

One of the most influential philosophers alive, Singer, 53, is a utilitarian

specializing in applied ethics; he studies issues relating to health care,

animal suffering, the poor, and the environment, and is the author or coauthor

of more than a dozen books. Singer, who gives 20 percent of his income to

famine-relief agencies, tries to live what he preaches. In an essay in The

New York Times Magazine, he argued that the ordinary American who has the

money to spare on luxuries is obliged to give most of it away to help people

suffering from poverty. He recently spoke with PAW's staff writer, Kathryn

Federici Greenwood, to elucidate his views.

Were you surprised by the tumult over your appointment?

Were you surprised by the tumult over your appointment?

I expected some. I guess it was slightly more than I expected, and particularly

the media response to it was larger than I expected.

Why have your views received so much attention?

It's the issues I discuss. It's the fact that I discuss them in clear

and plain language-I don't try to dress it up in jargon. And it's the protesters.

You might ask why did the protesters pick on me? That relates to the plain

language-they can easily pull sentences out of books and then think they

understand the meaning. The sentences may be out of context and people may

not understand the quotes, but the words look clear enough.

How did you become interested in issues about disabled infants?

When I learned that it was common practice for doctors to take infants

with serious disabilities and deal with them by withholding life-prolonging

treatment but not doing anything to actually hasten their deaths. The upshot

was that, depending on the nature of the condition, the infants might live

for weeks or months or even years, not being treated but not dying either,

sort of in a halfway state. That seemed to me to be just a pointless prolonging

of suffering. I came to the conclusion that it would not be right to try

to prolong the life of every child. So it must be justifiable, in some cases

at least, to end the child's life swiftly and painlessly.

Are you trying to make the point that doctors already are determining

what lives are worth living and when it's time to let people die?

Yes. People sometimes say you shouldn't judge the quality of life. To

which I respond, well, doctors already do that every day in every major

intensive care unit when they make decisions about what treatment to give

or not to give. We're already well down this road. It's not a question of

whether to go down it or not. So let's do it openly. Let's talk about where

we are, where we're going, and what's the best way to ensure that we don't

go where we don't want to go.

What are the range of views you cover in the seminar you are teaching

on Questions of Life and Death?

The views that the students are asked to read range from mine to those

of Germain Grisez and Joseph Boyle [in their book Life and Death with Liberty

and Justice], who present a viewpoint that is consistent with that of the

Roman Catholic Church. What I want students to go away with is a sharper

sense of what the issues are and what the arguments for and against different

viewpoints are in the areas we're discussing.

Clarify for me when you believe a baby becomes a person, as you define

"person," and therefore has a right to life?

Babies become persons when they develop some kind of awareness of themselves

as existing over time. That is, when they can grasp that they are the same

being who existed previously and who may exist in the future. As for saying

exactly when that happens, I can't. I don't think anyone can. Though I would

say it happens sometime during the first year of life but not in the first

month of life. That's why I've suggested putting a clear boundary on the

time within which it is justifiable to kill a severely disabled infant.

At one point I suggested a 28-day boundary. But I no longer think that that

will work. It's too arbitrary. I don't think you would get people to recognize

that there's a big difference in the wrongfulness of killing a being at

27 or 29 days. So what do you do? I think you need to look at it on a case-by-case

basis given the seriousness of the problems and balance that against the

age of the child.

Have you ever received letters from parents of children born with

severe disabilities who had to make difficult decisions about their care?

I've had letters from people who were worried about whether they did

the right thing. I've also received letters, including some just recently,

from parents who have read my work and are now more angry than they were

before at what the doctors did in keeping their children alive. Some parents

said the doctors basically had given them no choice about whether to operate

on their child. The parents used langauge like "They got to play with

their toys," meaning their medical equipment, "and left us with

a child who has a terrible life."

You have said that the U.S. seems to be a less caring society than

every other economically developed society in the world. Why do you think

that?

It may be that the American tradition makes people think in terms of

their rights rather than their responsibilities or obligations to others.

And that makes the community a more individualistic one. The clearest figures

are the foreign aid figures where the U.S. is at the absolute bottom of

economically developed countries in terms of what it gives as a percentage

of gross national product.

In terms of the lack of care for American citizens, the figures are a

little harder to pick out. I guess I'm aware of two things: Most obviously,

that there is no national health insurance, and that you see more homeless

people sleeping rough in New York City than you do in any Australian city,

for example. So something is going on here.

What are your observations about people in the U.S. and our treatment

of animals?

America is really falling behind the rest of the civilized world in its

care of animals. Europe is now moving forward in eliminating the most confining

forms of factory farming. They're phasing out the battery cages for hens,

which means that European hens will be able to stretch their wings, to walk

around freely, to lay their eggs in a nest. American hens will still be

trapped in little wire cages, unable even to stretch their wings.

Why do you think we are behind the mark on the care of animals?

The American political system is unresponsive to concerns like this that

do not have a lot of money behind them and that face politically influential

groups such as agribusiness that have billion-dollar corporations with millions

of dollars to spend on congressional lobbyists.

Would you like to clarify any of your views that you feel have been

misrepresented?

There was a letter in a recent Princeton Alumni Weekly that again quoted

this line about "defective infants." It's the emphasis on defective

that I find really unfair because the letter writer is quoting from a book

published in 1979. If the writer bothered to look at the 1993 edition of

Practical Ethics, he would find the langauge has changed to "disabled."

It's a little like accusing someone of having a negative attitude to African-Americans

because they used "Negro," quoting a speech from the 1950s. Martin

Luther King, Jr., used that word. The fashions change in terms of the language

you use.

Another important point is that people sometimes say that I have more

compassion for animals than I do for humans. I have an essentially unified

position: I am opposed to unnecessary suffering whether it's a human or

an animal. A lot of the suffering we inflict on nonhuman animals is unnecessary

and in some cases pointless. And I want to put a stop to that. The same

is true in regard to human beings.

Have you ever been faced with making a life and death decision for

a loved one?

My mother has Alzheimer's. I guess it's reaching the point where I have

to think about what treatment I would provide for her if she were to become

physically ill and in need of life support.

Do you see any conflict between your spending considerable money on

the care of your mother and your principle of spreading out wealth to help

the most people?

Yes. In a sense, my spending money on my mother's care is in conflict

with that principle. But so is the fact that I flew back to Australia to

visit my daughters at Christmas. That money could also be better spent elsewhere.

I've never claimed that I live my life perfectly in accordance with those

principles of sharing my money as much as I should.

What role do you see yourself playing in society?

I see the philosopher's role as one of challenging society to think clearly

about some things it might take for granted. In that way philosophers are

gadflies. Like Socrates, they run the risk of being condemned for it. Their

role is to get people to question things that they might not otherwise have

questioned.

What changes do you hope to effect?

I would like to see concrete progress in the U.S. of the kind that is

happening in Europe in terms of recognizing that farm animals ought not

to be deprived of the ability to move around or stretch their limbs. In

the area of bioethics, I would like to help develop alternative approaches

to some of these end-of-life decisions. Generally, I would like to stimulate

some reexamination of the idea of the sanctity of human life so that people

are not locked into particular positions but can look at cases in a more

flexible way that will lead to better outcomes.

Do you think religion affects people's ethical reasoning?

Religion has a major impact-basically in stopping people from thinking.

This is not true of every religion; it's a generalization, but there are

some religions, some ways of interpreting religions, that give you the sense

that you know the answers. You've got them laid down as dogma or revelation

or what your minister or priest or guru tells you, and you stop thinking.

That's a bad thing.

Do you think your being an atheist affects your philosophy?

It probably does, although there are some theists who would reach the

same conclusions. But it's certainly easier to reach them if you are not

religious. And probably people who are strongly committed to the traditional

religions like Christianity would not be likely to come up with the same

views that I hold.

...............

We are all murderers

from Practical Ethics (Cambridge University Press, 1993)

We cannot avoid concluding that by not giving more than we do, people

in rich countries are allowing those in poor countries to suffer from absolute

poverty, with consequent malnutrition, ill health, and death. This is not

a conclusion that applies only to governments. It applies to each absolutely

affluent individual, for each of us has the opportunity to do something

about the situation; for instance, to give our time or money to voluntary

organisations like Oxfam, Care, War on Want, Freedom from Hunger, Community

Aid Abroad, and so on. If, then, allowing someone to die is not intrinsically

different from killing someone, it would seem that we are all murderers.

. . . The uncontroversial appearance of the principle that we ought to prevent

what is bad when we can do so without sacrificing anything of comparable

moral significance is deceptive. If it were taken seriously and acted upon,

our lives and our world would be fundamentally changed. For the principle

applies, not just to rare situations in which one can save a child from

a pond, but to the everyday situation in which we can assist those living

in absolute poverty. In saying this I assume that absolute poverty, with

its hunger and malnutrition, lack of shelter, illiteracy, disease, high

infant mortality, and low life expectancy, is a bad thing. And I assume

that it is within the power of the affluent to reduce absolute poverty,

without sacrificing anything of comparable moral significance. If these

two assumptions and the principle we have been discussing are correct, we

have an obligation to help those in absolute poverty that is no less strong

than our obligation to rescue a drowning child from a pond. Not to help

would be wrong, whether or not it is intrinsically equivalent to killing.

Helping is not, as conventionally thought, a charitable act that is praiseworthy

to do, but not wrong to omit; it is something that everyone ought to do.

Reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press.

...............

Selected books by Peter Singer

Ethics into Action: Henry Spira and the Animal Rights Movement (Rowman

and Littlefield, 1998)

How Are We to Live? Ethics in an Age of Self-Interest (Oxford University

Press, 1997)

Rethinking Life and Death: The Collapse of Our Traditional Ethics (St.

Martin's Press, 1995)

Should the Baby Live? The Problem of Handicapped Infants, with Helga

Kuhse (Oxford University Press, 1985)

The Reproduction Revolution: New Ways of Making Babies, with Deane Wells

(Oxford University Press, 1984)

Practical Ethics (Cambridge University Press, 1979, 1993)

Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals (New York

Review/Random House, 1975, 1990)

Spend the money and run

Undeterred by low poll numbers, Steve Forbes '70 runs for president

again, plowing money into his candidacy

It should have been a moment of triumph: the back door of the vast room

in which 270 news reporters were watching live video of the first major

GOP debate of New Hampshire's 2000 presidential campaign burst open. In

marched four clean-cut gents in black suits, their arms laden with advance

copies of the Manchester Union Leader's front-page endorsement of Steve

Forbes. "Head and shoulders above the others," the newspaper gushed.

"One tough, smart customer."

It should have been a moment of triumph: the back door of the vast room

in which 270 news reporters were watching live video of the first major

GOP debate of New Hampshire's 2000 presidential campaign burst open. In

marched four clean-cut gents in black suits, their arms laden with advance

copies of the Manchester Union Leader's front-page endorsement of Steve

Forbes. "Head and shoulders above the others," the newspaper gushed.

"One tough, smart customer."

But in the next morning's reports on TV and in the press, it was Bush

and McCain, Bush and McCain. Forbes and his big endorsement were throwaway

lines. And even in The Union Leader's inky kiss to Forbes, the paper noted

that "Steve Forbes is not charismatic. Some would say he looks like

a geek."

In the days to come, Forbes's standing in the New Hampshire polls would

barely budge from the 7 or 8 percent rut he'd been in for months. Which

wouldn't be quite so painful if Steve Forbes '70-third-generation publisher

of the family business magazine, mega-millionaire, and Princeton trustee-had

entered the presidential derby simply to fulfill the goals he set in his

graduation yearbook entry: "To enter the field of publishing and to

dabble in politics."

Despite two presidential campaigns into which he has pumped more than

$50 million of his own money only to remain firmly in the second tier, Forbes

insists he is no mere dabbler. "I'm in this to win," he says,

stabbing the air with his cupped left hand, flashing the smile that seems

to unnerve voters with its suddenness.

Just before an early morning news conference at which Forbes announced

The Union Leader endorsement, an aide shows the candidate a slip of paper

on which his reaction has been scripted: "I am honored! I am flattered!

I am pumped!"

But as the session unfolds, Forbes can bring himself to say only this:

"As the kids would say, I am pumped." The cynics in the room groan.

Later, Forbes's New Hampshire press secretary, Dan Robertson, says that

his man's "demeanor doesn't really change. He's just a serious guy."

It must indeed be trying for Forbes as, for the fifth time in one afternoon

of campaigning, he is on the defensive, answering questions about the very

purpose of his candidacy: "I have more substance than just about all

the other candidates put together," he says.

Even if he does have to say so himself, it's a reasonable statement.

Forbes is one of the few figures in this race who can and will field off-the-cuff

questions on anything from taxes to Timor. He is well versed in the way

that serious candidates were once assumed to be, but no longer are. And

he has certainly put his money where his mouth is; this is not a campaign

that skimps on advertising, staffing, or any other political basics. Through

October 15, Forbes had personally contributed $16.3 million of the $20.6

million his campaign had raised, according to the latest Federal Elections

Commission records.

The early results, however, have been minimal: While the departures of

Dan Quayle, Elizabeth Dole, and Lamar Alexander have given Forbes the position

of dominant conservative in the Republican race, he remains little more

than a blip in the polls and in the hearts of voters in the crucial early

primary states.

Yet the candidate shows no sign of frustration. He has, in fact, put

a new coat of paint on this year's model. In 1996, Forbes was virtually

robotic in his allegiance to his message of "Hope, Growth, and Opportunity,"

repeating his flat-tax mantra no matter what the question, no matter how

mind-numbing the experience for his staff and the reporters who followed

him. This year, Forbes will, if the stars are in the right alignment, provide

thoughtful answers to questions that dare to stray from his tripartite platform

of saving Social Security by privatizing it, junking the IRS, and murmuring

sweet nothings in the direction of social conservatives. He has a habit

of listing his social concerns by spinning out a phrase or two on the coarsening

of the culture ("There's no sense of decorum or dignity anymore"),

the evils of the "if it feels good, do it" mentality, and the

weakness of public education, which he would solve with school choice and

charters.

Then, at the end of the list, he simply says the words, "and the

life issue." One of Forbes's top aides-one of several who joined the

campaign after giving up on Pat Buchanan's long-running crusade-says he

feels certain that Forbes is sincere in his newfound opposition to abortion,

but another aide isn't so sure: "Well, it wasn't high on his list in

'96, and it's not what animates him now," the staffer says.

One new issue that has enlivened Forbes is Princeton's decision last

year to hire the controversial philosopher Peter Singer. After initially

saying that he would not withhold his contributions to the university, Forbes

reversed course in October and swore never to give another dollar to Princeton

as long as Singer-a bioethicist who has written in favor of euthanasia for

the terminally ill and infanticide for severely disabled babies-remains

on the faculty. (See preceding story.) The university will miss Forbes's

gifts-the son has been "a generous donor to the university over the

years," says Van Zandt Williams '65, Princeton's vice-president for

development, though he declined to release details of the gifts. (Forbes's

father, the late publisher Malcolm S. Forbes '41, donated $7 million to

Princeton in the early 1980s for faculty support and for the renovation

of Princeton Inn College, which was renamed in Steve Forbes's honor. Figures

published in the university's Gifts to Princeton, dating from 1986 through

1999, show that the Forbes family-including Malcolm '41, Christopher "Kip"

'72, the Forbes Foundation, and Forbes Magazine Collection-gave just over

$2 million. That number does not include the value of numerous works of

art donated to the Art Museum. Individual figures for members of the Forbes

family are not published.)

Forbes does not include the Singer controversy in his campaign speeches,

but he is quick to expound on his decision to take on the university. "These

kind of views should have gone out with Nazism," he says. "I've

long felt that eugenics and euthanasia are profoundly wrong, and I wrote

about that long before I got into the public square." Forbes reiterated

his intent to remain on the Board of Trustees "to keep working for

my principles."

Although the university declined to reveal details of Forbes's role in

the decision to hire Singer, citing the confidentiality of trustee meetings,

board sources said Forbes did vote to approve Singer's employment-which

Forbes's campaign manager, Bill Dal Col, agrees is probably what happened.

But Dal Col says that as soon as Forbes realized who Singer was, "he

asked for the appointment to be rescinded."

"I think my position has already had an impact," Forbes says.

"The university is going to be more conscientious about this kind of

hiring now." He offered no evidence for that statement, and dismissed

the unusual rebuke he received from Robert H. Rawson, Jr. '66, the chairman

of the board's executive committee. Rawson publicly criticized Forbes for

being unwilling to accept the "fundamental responsibility of trusteeship"

of protecting academic freedom.

The very fact that Forbes would address an issue that falls outside his

core campaign message is a change from his 1996 approach. But to say that

Forbes seems more relaxed this time is not to say that he has become Bill

Clinton.

Forbes remains incapable of schmoozing with either reporters or voters.

His meet-and-greet appearances are painful to watch: In Amherst, New Hampshire,

he walks into the Black Forest Café and Bakery, dutifully shakes

hands with the cashiers and countermen, politely thanks a couple of button-wearing

supporters for their help, and in nine quick conversations with potential

voters, he asks not a single question, makes not a single comment about

the voters' lives, jobs, clothing, or anything else. In the three minutes

it takes Forbes to move from his bus to his lunch table, chatty John McCain

would have made six jokes and found three old military buddies; winking

George W. Bush would have made half a dozen women remember that racy football

player who'd once asked them out on a date; and concerned Al Gore would

have collected the family histories of a bunch of voters-as well as ascertaining

the mileage they get on their minivans.

Forbes's primary tools for connecting with voters are his laserlike blue

eyes, a quick but awkward smile, and a handful of rhetorical flourishes

that seem to dovetail with what many voters think, yet leave most people

still searching for a candidate to call their own.

At the Village Green Market in the picturesque center of Amherst, bread

delivery man Charles Duggan spies Forbes picking up a bunch of newspapers

and some donuts ("My wife will kill me," Forbes says cheerfully),

and grabs the candidate's forearm: "You act like a real common man,

and yet you're a very wealthy guy!" Duggan says.

"You made my day!" Forbes replies, genuinely touched.

But moments later, the candidate is back to his script, one that relies

heavily on bashing Washington ("Washington wants to dominate us,"

"take it out of the hands of Washington politicians," "typical

Washington attitude") and bemoaning the state of an overtaxed, economically

stressed nation-a portrait that doesn't always ring true in an era of full

employment and the seemingly endless bull market.

In an assembly of candidates whose proposals are strikingly similar and

decidedly unambitious, Forbes stands out as someone who wants to rock the

boat. He still wins nods and occasional cheers with his 1996 lines about

gutting the IRS, and the talk-radio crowd is enchanted with his proposal

to scrap the current Social Security system and let taxpayers invest their

cash in the market.

Forbes will probably ride out the middle primaries at the bottom of a

narrowing pack, perhaps staying in the race all the way to the convention.

After all, he's invested this much already.

And while voters rarely get a glimpse of the puckishness that Forbes's

college friends recall, the candidate has lightened up some. When a Comedy

Central TV crew followed him around to examine exactly what this "rich,

well-fed candidate" is eating on the campaign trail, Forbes initially

ignored the fresh questions. But after a couple of days, he decided to play

along: After being caught on tape consuming a large burger and fries, he

told the video satirists, "I had red meat for lunch, and I had french

fries, which to me is a health food. And I had apple pie, so maybe that

will sit well with the voters."

Irony from the ultimate straight man?

Forbes's smile broadened beyond the usual grin. That sound bite from

earlier in the day reverberated: "As the kids would say, I am pumped."

Marc Fisher '80 is special reports editor of The Washington Post and

a columnist for The Washington Post Magazine.

Campus conservative

At Princeton Steve Forbes '70 set the stage for careers in publishing

and politics

Steve Forbes had a blast at Princeton. When he arrived in the fall of

1967, he was as out of step with the political and social norms as could

be-a conservative in a radical moment, a champion of business on a campus

awash in counterculture expressions. Yet Forbes relished the role he created

for himself. With a touch of his old man's flair for theatrics, the son

of one of America's premier capitalists set the stage for a career as a

provocative journalist, detail-oriented publisher, and iconoclastic politician.

Steve Forbes had a blast at Princeton. When he arrived in the fall of

1967, he was as out of step with the political and social norms as could

be-a conservative in a radical moment, a champion of business on a campus

awash in counterculture expressions. Yet Forbes relished the role he created

for himself. With a touch of his old man's flair for theatrics, the son

of one of America's premier capitalists set the stage for a career as a

provocative journalist, detail-oriented publisher, and iconoclastic politician.

Forbes arrived at Princeton from the private Brooks School in Andover,

Massachusetts, where he worked on the school newspaper and was involved

with the debating society and the Young Republicans. He continued all three

activities in college and beyond. During his sophomore year at Princeton,

Forbes launched a quarterly magazine called Business Today, just as his

father had started his own campus periodical, the Nassau Sovereign, which

Malcolm S. Forbes '41 called "the campus Fortune."

Business Today (BT), which continues to this day, was Forbes's way of

saying that not all students were letting their hair grow and picketing

Nassau Hall to protest the Vietnam War. Indeed, while campus dress standards

fell by the wayside, BT set its own rules for its student staff: No hair

below the collar and no mutton chop sideburns. Forbes's editorials had a

knack of getting under the skin of students to his left. He slammed Senator

Eugene McCarthy's presidential campaign: "This sleeping pill has aroused

the admiration of today's youth beyond explanation. Since when has petulance

been a substitute for wit?" He praised police crackdowns on student

demonstrations, calling it "refreshing" to see cops, "clubs

a-swinging."

In retaliation, Forbes says, the leftist Students for a Democratic Society

held a magazine-burning party for BT, and Forbes found himself on the receiving

end of 3 a.m. obscene phone calls. But James "Jimmy" Tarlau '70,

then a leader of SDS and now a labor organizer for the Communication Workers

of America in Trenton, says SDS had little interest in Forbes or BT. "He

was into doing a business magazine, so no one paid much attention to him.

He was irrelevant then, just as he's irrelevant now." The class poll

at the end of senior year elected Tarlau "Biggest Revolutionary"

and dissed Forbes by calling his Business Today "Worst Magazine."

But friends say Forbes was not a significant player in the turbulent

campus politics of the late '60s. "Some people were always at the Student

Center talking politics; Steve was not in that group," says Mickey

Pohl '70, a close friend of Forbes then and now. "But if you had a

precept with him, you could just stand back because Steve had such a command

of history."

Pohl does not challenge the media image of Forbes as charisma-challenged,

but says his friend had, even as an adolescent, an unusual ability to put

people at ease, especially people who might be wary of someone born to wealth.

"He obviously does not glide into a room like a football quarterback,"

Pohl says. "He wouldn't be on anyone's short list to be a club or party

chairman, but executor of your will, guardian of your children-he's the

obvious choice, for his honesty, his dependability, his reserve, and his

intellect."

Despite putting in 40-hour weeks at the magazine-Forbes skipped so many

classes, he listed cutting as one of his proud achievements in the Nassau

Herald-he found time to write a thoughtful thesis on the battle for the

1892 Democratic presidential nomination, and he maintained an active social

life: In his senior year, he met Sabina Beekman, a rector's daughter, at

a debutante ball in New York City. After a three-week romance, they were

engaged. These days, she accompanies him on the campaign trail. Two of Forbes's

five daughters attend Princeton, Catherine '00 and Moira '01. His other

Princeton relatives are his brother Christopher "Kip" '72, his

niece Charlotte '97, and his uncle Wallace '49.

Forbes broke with many of his fellow traditional Princetonians and declined

to join an eating club. He believed that political conservatism did not

conflict with the egalitarianism and sense of fairness that drove him to

reject the club system and eat at the Woodrow Wilson Society, a university-run

dining hall for upperclassmen.

While Forbes was certainly conservative in comparison to many of his

fellow students, he was considerably less doctrinaire than he may seem today.

Business Today celebrated bankers who chose to work in the inner cities,

endorsed Ted Kennedy's call for a draft lottery, and called on President

Nixon to fire Attorney General John Mitchell for his "wholesale slaughter

of basic civil liberties." Forbes even praised Ralph Nader '55, penning

a column in which he called the consumer advocate "business's most

unsung hero."

But in his thesis, Forbes railed against "New Deal liberalism"

and embraced a more freewheeling capitalism of the kind his family magazine

has celebrated over the decades. That Steve Forbes, the one intent on giving

Americans control of their own Social Security funds and dismantling the

IRS, has changed little over the years-still enchanted by ideas, still brimming

with enthusiasm.

-Marc Fisher '80 and

Jeremy Weissman '01

PAW remembers: Selections

from our first century

This year is PAW's 100th birthday. In 1900 the Princeton Alumni Weekly

succeeded The Alumni Princetonian, a weekly edition of The Daily Princetonian,

which had been in existence for six years and was unable to sell more than

500 subscriptions to the 6,000 alumni. PAW's first editor, Jesse Lynch Williams

1892, wrote in the premier issue, dated Saturday, April 7, 1900, that it

is fitting for alumni to be particularly well-informed. "This is a

duty and should be a pleasure." Over the course of the year 2000 we

will print excerpts selected from PAW's 100 years of issues that in our

opinion both inform and bring pleasure.

January 18, 1902

Smallpox scare

Smallpox has been alarming Princeton, just as it has other localities

this winter, but thus far nothing has happened to get excited about, and

the college . . . has very properly taken every known precautionary measure,

and is seeing to it that everybody is vaccinated. Two students have been

clapped into the contagious diseases annex of the Infirmary, and of these,

one had chicken-pox and is now over with it; the other's case was pronounced

at first varioloid, but later looked more like chicken-pox.

January 22, 1919

The Death of Hobey Baker '14

From Edward C. Olds '09's letter reporting the December 21, 1918, death

of airman Captain Hobey Baker '14, one of Princeton's greatest athletes

and the model for "Allenby" in F. Scott Fitzgerald '17's This

Side of Paradise: "I have just returned from Hobey Baker's funeral.

It has cast a cloud over the Second Army Air Service, where he was so very

well known and liked by officers and men. Knowing how much he has meant

in recent years to all Princetonians, I hasten to give you the facts about

his death." Baker had gone to the Toul Airdome to take a last trip

in his Spad, but instead took up the recently repaired plane of one of his

officers. "Both his officers and mechanics strongly urged him not to

do so, but he insisted. He took off, made a short turn to the right, and

was up only 150 metres over the field when the engine failed. He dropped

rapidly . . . nosed down to gain headway, started into a vrille and crashed,

being almost instantly killed."

January 27, 1941

Memorial: Scott Fitzgerald '17

Many of us of the Class of 1917 felt that a bright page of our youth

had been torn out and crumpled up when we learned of the death of Scott

Fitzgerald, who died of a heart attack in Hollywood, Calif., on December

21. Scott's whole early career is typified in his very first face to face

encounter with the authorities at Princeton. He needed extra points to be

admitted to the freshman class, and, on his unconventional plea before the

faculty committee that it was his seventeenth birthday, the members of the

committee laughed and admitted him. . . . He was aware of, and intensely

interested in, every fashion and custom, the history and background of every

undergraduate organization, and, above all, the personalities who composed

these organizations, and who later became the characters in his most popular

stories. His intense interest in every phase of the University's social

life and his eagerness to dissect it on every occasion made him a rare companion-interesting,

amusing, provocative, sometimes annoying, but never dull. . . . To his widow,

the former Zelda Sayre of Montgomery, Ala., and his daughter, Frances Scott

Fitzgerald, a junior at Vassar, the Class extends its sincere sympathy.

January 23, 1973

Princeton Club Liberated

As a postscript to our article on the Princeton Club of New York (PAW,

Nov. 21), we can report that there have been some changes made. Women-yes,

women, are now being freely admitted into the former "Men's Grill."

As they enter the room, they walk resolutely over the notorious and now

impotent stone inscription, "Where women cease from troubling, and

the wicked are at rest."

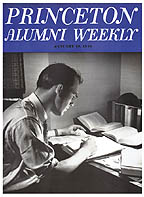

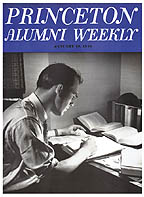

January 19, 1940

This week's cover picture, by Frank Kane, we

think amply conveys the message that mid-years are here again. The earnest

student is Henry M. Zeiss '40 (son of Carl H. Zeiss '07), and he was hard

at work preparing for his majors when we asked him to pose for a typical

student-studying-for-exams picture. He hoped that the convincing result

won't lead family or friends to expect too much from his marks. "Remember,"

he says, "it was posed."

This week's cover picture, by Frank Kane, we

think amply conveys the message that mid-years are here again. The earnest

student is Henry M. Zeiss '40 (son of Carl H. Zeiss '07), and he was hard

at work preparing for his majors when we asked him to pose for a typical

student-studying-for-exams picture. He hoped that the convincing result

won't lead family or friends to expect too much from his marks. "Remember,"

he says, "it was posed."

January 19, 1965

January 19, 1965

Princeton salutes its returning Olympic heroes (and heroine) at the Harvard

football game: Miss Lesley Bush of the town, who after assiduous training

with the University's diving coach, Bob Schneider, won a 10-meter gold medal;

at the left, John Allis '65 of the cycling team; and, of course, Bill Bradley

'65 of basketball fame. Photo by Bob Matthews.

GO TO

the Table of Contents of the current issue

GO TO

PAW's home page

PAW@princeton.edu

Faculty appointments seldom create an uproar. But when Princeton hired

Australian philosopher Peter Singer away from Monash University in Melbourne

and appointed him as DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at the university's Center

for Human Values, his controversial views on infant euthanasia became more

widely known in this country, and the press, some alumni, and certain special-interest

groups reacted loudly. Disabled rights and pro-life activists protested

his first day of class. And the university has taken precautions to protect

his safety, routinely stationing security guards at his public speeches

on campus and putting packages with unfamiliar return addresses through

an airport-style scanner before he opens them.

Faculty appointments seldom create an uproar. But when Princeton hired

Australian philosopher Peter Singer away from Monash University in Melbourne

and appointed him as DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at the university's Center

for Human Values, his controversial views on infant euthanasia became more

widely known in this country, and the press, some alumni, and certain special-interest

groups reacted loudly. Disabled rights and pro-life activists protested

his first day of class. And the university has taken precautions to protect

his safety, routinely stationing security guards at his public speeches

on campus and putting packages with unfamiliar return addresses through

an airport-style scanner before he opens them. Were you surprised by the tumult over your appointment?

Were you surprised by the tumult over your appointment? It should have been a moment of triumph: the back door of the vast room

in which 270 news reporters were watching live video of the first major

GOP debate of New Hampshire's 2000 presidential campaign burst open. In

marched four clean-cut gents in black suits, their arms laden with advance

copies of the Manchester Union Leader's front-page endorsement of Steve

Forbes. "Head and shoulders above the others," the newspaper gushed.

"One tough, smart customer."

It should have been a moment of triumph: the back door of the vast room

in which 270 news reporters were watching live video of the first major

GOP debate of New Hampshire's 2000 presidential campaign burst open. In

marched four clean-cut gents in black suits, their arms laden with advance

copies of the Manchester Union Leader's front-page endorsement of Steve

Forbes. "Head and shoulders above the others," the newspaper gushed.

"One tough, smart customer." Steve Forbes had a blast at Princeton. When he arrived in the fall of

1967, he was as out of step with the political and social norms as could

be-a conservative in a radical moment, a champion of business on a campus

awash in counterculture expressions. Yet Forbes relished the role he created

for himself. With a touch of his old man's flair for theatrics, the son

of one of America's premier capitalists set the stage for a career as a

provocative journalist, detail-oriented publisher, and iconoclastic politician.

Steve Forbes had a blast at Princeton. When he arrived in the fall of

1967, he was as out of step with the political and social norms as could

be-a conservative in a radical moment, a champion of business on a campus

awash in counterculture expressions. Yet Forbes relished the role he created

for himself. With a touch of his old man's flair for theatrics, the son

of one of America's premier capitalists set the stage for a career as a

provocative journalist, detail-oriented publisher, and iconoclastic politician. This week's cover picture, by Frank Kane, we

think amply conveys the message that mid-years are here again. The earnest

student is Henry M. Zeiss '40 (son of Carl H. Zeiss '07), and he was hard

at work preparing for his majors when we asked him to pose for a typical

student-studying-for-exams picture. He hoped that the convincing result

won't lead family or friends to expect too much from his marks. "Remember,"

he says, "it was posed."

This week's cover picture, by Frank Kane, we

think amply conveys the message that mid-years are here again. The earnest

student is Henry M. Zeiss '40 (son of Carl H. Zeiss '07), and he was hard

at work preparing for his majors when we asked him to pose for a typical

student-studying-for-exams picture. He hoped that the convincing result

won't lead family or friends to expect too much from his marks. "Remember,"

he says, "it was posed." January 19, 1965

January 19, 1965