|

Web

Exclusives:Features November

7, 2001: By Kate Swearengen '04

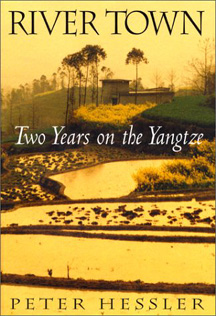

Peter Hessler must be in denial. After graduating from Princeton in 1992 with a degree in English, and after two years at Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, Hessler decided to travel. A visit to China got him hooked. Fascinated by the country, and troubled by what he describes as "the politicization of literature in the West," he joined the Peace Corps and asked to work in China. Assigned to Fuling, a Sichuanese town at the confluence of the Yangtze and the Wu Rivers, Hessler taught English literature at a teachers' college. He also learned Chinese. Life in a part of the world rarely visited by Americans provided the material for his book, River Town: Two Years on the Yangtze (HarperCollins). Published this year by HarperCollins, River Town is an account of Hessler's experiences in China from 1996-1998. While much of the book is spent describing daily life in Fuling and the beauty of the surrounding countryside, a central theme prevails. More than anything else, River Town is about Hessler's efforts to blend in with his surroundings, while at the same time retaining those elements that identify him as an American. "But I found I good spot in the hills high above the Wu River, where I ate dinner and read Ted Williams's autobiography. I decided that I would read that book every spring for the rest of my life--there was something distinctly American about his voice -- the cockiness and the earthy slang and the rhythms of his prose. And especially I liked the way the book began: "I wanted to be the greatest hitter who ever lived...'" The two years that Hessler spent in Fuling were important ones for China. The death of President Deng Xiaoping, and the wrenching modernization brought about by China's movement toward a market economy, heralded a change in the Chinese people's perceptions of their government. Even Fuling itself would be transformed: The Three Gorges Dam Project, designed to provide more electricity, better flood control, and improved transportation for China, will eventually flood a great deal of land, displacing two million people and changing Fuling's character forever. Hessler's challenge was to describe Fuling and its inhabitants at this particular juncture in time, before change set in. It is significant that the best preparation for this task had occurred almost 10 years before, and halfway around the world. "No," Hessler says when I ask him if he did any summer writing or publishing internships during his years at Princeton. "I always went home to Missouri in the summer. The summer after my junior year, I did an ethnography project in Sikeston, and talked to kids about race and poverty problems." Sikeston is a rural town in southeast Missouri. It is surrounded by soybean and cotton fields, has a population of about 18,000, and is home to Lambert's Cafè, which describes itself as "the only home of throwed rolls." According to Hessler, his efforts to describe Sikeston by conveying "the feeling of the place" prepared him more for his book than anything else. It's not the sort of thing that one would typically describe as an influential experience, but then again, Hessler's experiences have been anything but typical. This year he traveled to Ulan Bator to cover a Mongolian rap group for the Boston Globe. Currently, he's driving a Jeep through western China in order to write a piece about Shang dynasty archaeology for National Geographic. He's also working on his next book. For the most part, Hessler speaks positively about his years at Princeton. An English major, he credits John McPhee's The Literature of Fact class for exposing him to nonfiction writing. During his time at Princeton, Hessler ran cross-country and track, and was a member of the Student Volunteers Council. While he did not contribute regularly to campus newspapers, he wrote his first published article, an account of going door-to-door with a Mormon student, for the Princeton Alumni Weekly. Though Princeton was a formative experience for Hessler, he is very definite about the divergent path he took to reach critical success as a writer. "According to Princeton, everything has to add up logically to a certain goal," Hessler says. "One of the most worthwhile things I did in college was going to Trenton twice a week to read to kids in a foster home." He adds that he derived the most fulfillment from experiences that were unexpected, like his summer project in Sikeston. "Take my experiences in China, for example," Hessler says. "I learned so much more in the Peace Corps about writing and about life than in two years at Oxford."

|

Princeton

students joke that 90 percent of each graduating class will go on

to be consultants or investment bankers. The other 10 percent, they

say, are in denial.

Princeton

students joke that 90 percent of each graduating class will go on

to be consultants or investment bankers. The other 10 percent, they

say, are in denial.

Hessler's

discussions with his students and Chinese tutors are a case in point.

Although well aware of the flaws in American society and government,

Hessler often found himself defending the policies of the U.S. At

the same time, he regretted the cultural barriers that existed between

himself and his students. This dichotomy, the division between the

Western and Eastern sides of Hessler's personality, are particularly

evident in the following lines from River Town:

Hessler's

discussions with his students and Chinese tutors are a case in point.

Although well aware of the flaws in American society and government,

Hessler often found himself defending the policies of the U.S. At

the same time, he regretted the cultural barriers that existed between

himself and his students. This dichotomy, the division between the

Western and Eastern sides of Hessler's personality, are particularly

evident in the following lines from River Town: