|

Web Exclusives: PawPlus An Italian goat’s ‘message of gratitude’ Editor’s note: The Oct. 30, 2007, announcement that the University Art Museum would be returning ancient art objects to the Italian government that had been taken illegally from the country brought to mind another Italian artifact – an 1,800-year-old marble goat head – with Italian and Princeton connections. The goat’s head attracted widespread news coverage a half-century ago; below are excerpts from PAW’s coverage. A Goat Goes Home to Rome (PAW, May 15, 1953) An 1,800-year-old goat is being restored to its rightful owner. Ernest T. DeWald [*1914], director of the Princeton Museum, has presented the modest treasure to Dr. Elio Giuffrida, Italian vice-consul in Newark, for return to the Museo dei Conservatori on Rome’s Capitoline Hill. Princeton had been in possession of stolen goods. Last fall, four years after the goat had been obtained by the Princeton Museum in the open art market, Dr. DeWald’s assistant, Miss Frances Jones, discovered that the head belonged in Rome – though the Romans did not know it. Like most Italian works of art, the goat had been placed in storage at the outbreak of World War II and its subsequent disappearance had not yet been discovered. Ironically enough, the head was purchased for the Princeton Museum by Professor DeWald, who was decorated by the Italian Government as well as by the American and British governments for his World War II services in safeguarding Italy’s art treasures and then returning them to their rightful owners. ON THE COVER: Baron de Ferrariis Salzano (left), Italian Consul General in New York, affectionately pats the 1,800-year-old goat’s head which he returned to Princeton last week in a gesture of international friendship. Looking distressed at the moment of parting is the Marchese Uguccione Ranieri di Sorbello, cultural attaché to the Italian Embassy. A description of the ceremony and a review of the goat’s extraordinary odyssey will be found on this page. (Photograph by Howard Schrader) “I do not dare to tell you,” said the Consul General of Italy, “that Billy can act as an ambassador of the ‘Grandeur that was Rome.’ … But Billy does return to Princeton as a gift from my Government and from the City of Rome with a message of gratitude … for what the Americans, under the leadership of a man from Princeton, did even in the stress of battle to preserve the works of art of our common heritage.” With these words, Baron de Ferrariis Salzano presented to President Dodds the head of a goat, carved in marble. Witnessed by some four-score dignitaries and friends of the Art Museum, the presentation ended an unusually appealing saga of international culture and friendship. As close readers of the WEEKLY know, the story starts in 1948 in an antique shop in Rome. There, Professor Ernest T. DeWald [*1914,] director of the Princeton Art Museum, discovered the goat and purchased this fragment of what was once a life-sized statue. Dr. DeWald – “the man from Princeton” of whom the Consul General spoke – had been director of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Subcommission of the Allied Commission in Italy and had been decorated by three governments for his work in safeguarding Italy’s art treasures and restoring them to their rightful owners. For three years Billy the Goat resided in the Princeton Art Museum, where it won many friends and admirers. Then, in the course of preparing an article on this acquisition, Miss Frances Jones, assistant to the director of the museum, discovered in the catalogue of the Museo dei Conservatori in Rome a photograph and description of an identical goat’s head. When the director of the Museo dei Conservatori was advised, he confessed that their goat’s head was missing, but that its disappearance from a storage vault had not been noticed until Professor DeWald reported its presence at Princeton. It is thought that a construction worker made off with the art treasure during the period when the museum was reinforcing its building against Allied bombs. Last year, the Italian vice-consul called at Princeton to pick up the goat (PAW May 15, 1953). Billy, however, got no further than New York. After an exchange of correspondence with their representatives in the United States, the Italian Government and the City of Rome, to whom the goat belonged, decided to present it to Princeton as a gesture of friendship and an expression of gratitude for Professor DeWald’s wartime service in Italy. “This ancient beast,” said the consul general as he returned the goat, “was once a symbol of joy and of the pagan relish for life. Witness the fact that one finds the goat mixed up in all woodland stories of nymphs and satyrs of ancient mythology. Looking at the doleful expression of our present Billy, one could almost guess that he is burdened with an unutterable sadness at the thought that all that is past. What is not passed, however, is the link which even a simple goat’s head represents with the great days of Rome — a time and a culture from which, in spite of all the intervening centuries, so much of our present civilization derives. “The hands that carved Billy have long since returned to

dust. Little did the unknown sculptor know that his sweet, sad,

and wise little goat would one day travel over the unknown Ocean

Sea and find friends and admirers on shores so distant from his

native city.”

|

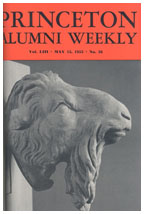

ON THE COVER: As close readers of the metropolitan press will

know, this week’s cover photograph is not merely decorative

but newsworthy. The story is told on the opposite page. Suffice

it to say here, the goat is an outstanding work by an unknown Roman

sculptor of the second century A.D. and was, until his recent departure

for Rome, one of the most popular possessions of the Princeton Art

Museum. Measuring 11 inches from the tip of his beard to the top

of his head, the “goat” is probably a fragment of a

life-sized statue. (Photo by Reuben Goldberg)

ON THE COVER: As close readers of the metropolitan press will

know, this week’s cover photograph is not merely decorative

but newsworthy. The story is told on the opposite page. Suffice

it to say here, the goat is an outstanding work by an unknown Roman

sculptor of the second century A.D. and was, until his recent departure

for Rome, one of the most popular possessions of the Princeton Art

Museum. Measuring 11 inches from the tip of his beard to the top

of his head, the “goat” is probably a fragment of a

life-sized statue. (Photo by Reuben Goldberg)

News in Brief (PAW, Jan. 29, 1954)

News in Brief (PAW, Jan. 29, 1954)