Sam Wang — explorer of the brain and wrangler of political polls — made a prediction in 2012 that turned out to be wrong.

A professor of molecular biology and the Princeton Neuroscience Institute, Wang wanted to know why. His pursuit of the answer led him to dive into a new area of inquiry — political redistricting. Four years later, he has published an article in one of the nation's top law reviews detailing a relatively simple way for judges to identify when a set of districts has been unfairly drawn to benefit a given political party.

Not bad for a self-described political hobbyist.

But whether he is working in his lab on campus to better understand the brain region known as the cerebellum, crunching numbers on dozens of polls to present a clear picture of the presidential race or hunting for evidence of partisan intent in redistricting, Wang says he is always looking to find order in the chaos of large amounts of data.

"When faced with complex data, the difficulty is to extract an understandable simple meaning from a large data set," Wang said. "My general approach to data analysis, to the extent possible in neuroscience, is to take all the observations we make in the lab and try to come up with some relatively simple fact that can be stated about the data. The thing that's in common in these other areas is that I'm just using tools that I use in the course of my research."

Wang's ability to turn a jumble of individual polls into meaningful insights about political races has gained him a loyal group of readers at his Princeton Election Consortium website since 2004. But that was also the source of his incorrect 2012 prediction. He rightly predicted that Democratic candidates would get more votes than Republican candidates in House races across the country. He also foretold that Democrats would regain control of the House. That's where he was wrong.

"The incorrect prediction bothered me," Wang said. "I wanted to figure out why I was wrong. My readers — whom I rely on a lot — pointed out that partisan redistricting had been pretty intense in 2010 and I discovered it had been asymmetric, benefiting Republican candidates."

The search for a standard

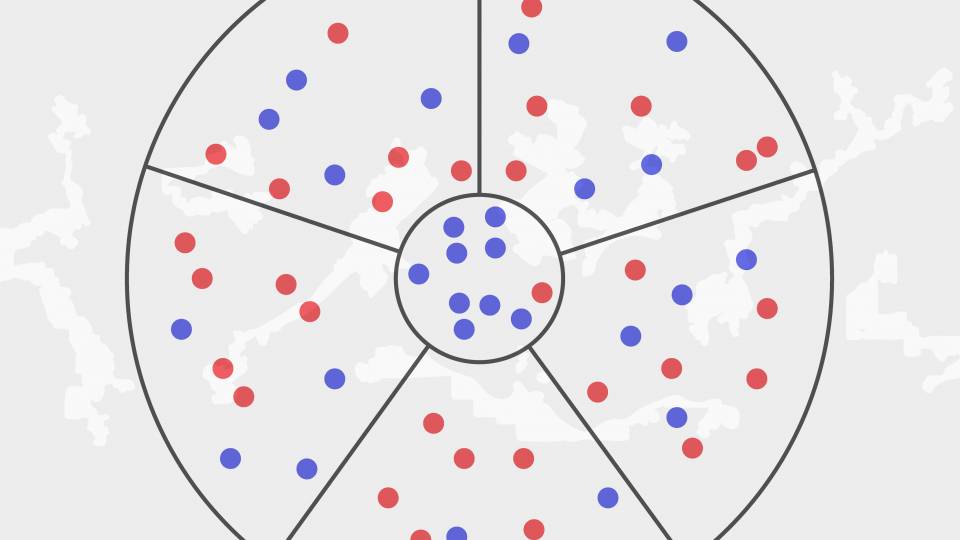

While the Supreme Court has held that partisan gerrymandering — constructing a set of districts to benefit one party over another — is subject to court action, Wang said no standard has been adopted to identify whether it has taken place. Because of that, Wang said, court cases about redistricting often feature parades of expert witnesses and countless electoral maps. He wanted to suggest an alternative approach.

"My goal was to come up with something simple enough that a judge could jot it down on a piece of paper or do it in an Excel spreadsheet," he said. "I think it would be nice to come up with something the judge could use, and there wouldn't be a need for experts."

One part of Wang's three-part test relies on a computer simulation to estimate appropriate levels of representation for a given level of popular vote and provides a way to measure the effects of gerrymandering.

The other two parts, which can be used to help evaluate the intent of redistricting, rely on well-established statistical principles and can be carried out on a calculator. Those tests identify whether the redistricting has been designed to pack one party's voters into as few districts as possible, giving them big wins but minimizing their impact overall, while geographically spreading the other party's voters so the gerrymandering party is able to win a larger number of districts, though by a smaller margin.

And to make the task even easier, Wang has created tools to carry out the tests on a new website. He offered an overview of his approach in a New York Times guest column and lays out the details in an article published in July in The Stanford Law Review. His proposal placed second in the 2016 First Amendment Gerrymander Standard Writing Competition organized by the group Common Cause.

"Professor Wang's proposal is a clear and thoughtful approach to partisan gerrymandering," said Derek Muller, an associate professor of law at Pepperdine University and one of the judges of the Common Cause competition. "It answers the right questions, addressing not simply the political science perspective but also the legal framework judges will face. Indeed, the paper introduces an element specifically designed to aid judicial resolution of such disputes, one of the issues that most frequently complicates partisan gerrymandering claims."

Wang's hope is that not only will the standard be used in court, but that he won't even need to be there as an expert witness.

"I don't need to be go to court because it's clear enough that I don't need to be there," Wang said. "I can stay here and do my neuroscience research."

In the lab

Right now, that research entails working to understand how the cerebellum, which is important to movement, affects cognitive function. The cerebellum is the most commonly aberrant brain region in people with autism, Wang said, though the reason remains unclear. His lab is exploring the theory that the cerebellum plays a teaching role during sensitive periods of development and plays an important role in organizing the rest of the brain. In experiments using mice, Wang and his colleagues deactivate parts of the cerebellum during parts of development and measure the impact on the brain.

"We want to know what patterns of inactivation of the cerebellum are linked with social deficits," Wang said. "That requires analytical techniques for dealing with large amounts of data. If our hypothesis is true, it will show how the cerebellum contributes to emotional and cognitive maturation, and it will show one way by which brains can become autistic. It could also make some contribution to understanding where autism comes from generally."

Poll wrangler

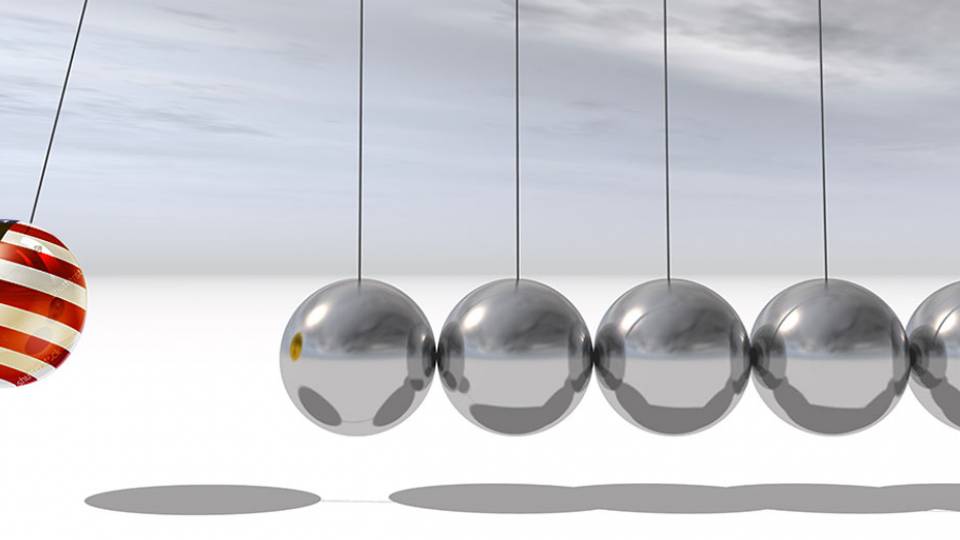

As for his polling website, it's largely on autopilot these days. He posts updates on the presidential campaign and polling issues, but the aggregation of state-level polls into what he calls the "meta-margin" now happens automatically. Updated four times daily and placed prominently at the top of the site, the meta-margin gives a sense of how far ahead one candidate is in the presidential race. Put another way, it measures the amount of opinion swing needed to result in an Electoral College tie.

Wang is also sharing his insights in a new forum, the "Politics & Polls" podcast, which he co-hosts weekly through the Nov. 8 general election with Julian Zelizer, the Malcolm Stevenson Forbes, Class of 1941 Professor of History and Public Affairs.

"Sam is a very original voice in the world of political analysis," Zelizer said. "He manages to take substantial amounts of quantitative data and connect that information to the debates that are shaping politics. We are excited about our new podcast, which aims to bring our two intellectual worlds together."

So is Wang paying close attention to this year's presidential race?

"Well, kind of, as much as anyone is" he said. "But if I want to know what's happening in the race, I do what my readers do, which is I log on to my website and look at the top number."