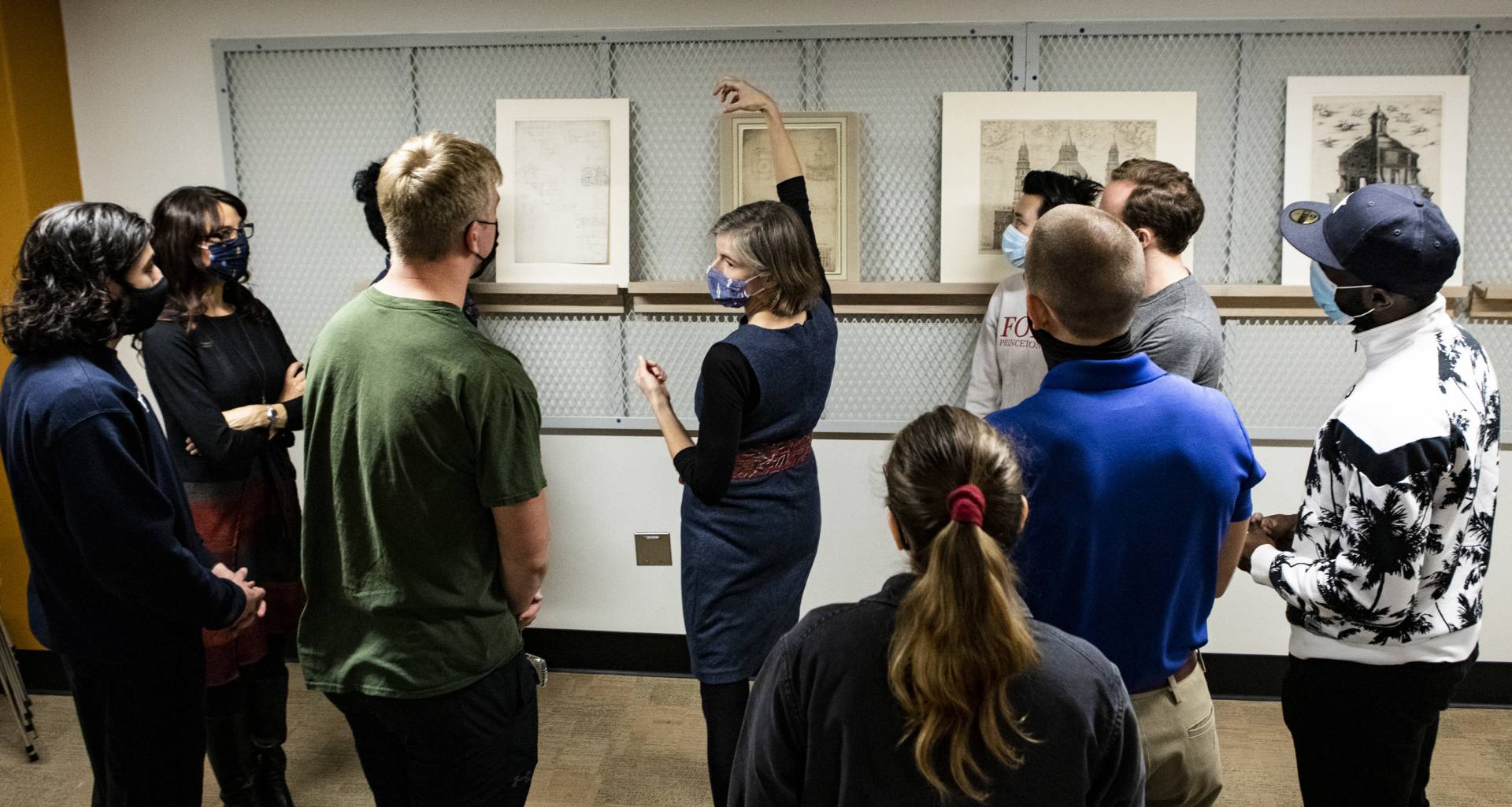

Carolyn Yerkes (front, second from right), associate professor of art and archaeology, and Carolina Mangone (far right), assistant professor of art and archaeology, walk with some of their “Renaissance Art and Architecture” students from a lecture in Green Hall to a precept in Firestone Library.

"No book, screen or virtual experience can compare to viewing a work of art in person,” said Maia Julis, a member of the Class of 2023 who is concentrating in art and archaeology. “In every class where I have had the privilege to stand in front of artworks, professors always say, ‘get closer,’ ‘move forward,’ ‘you can’t see from back there.’

"Professors stress the importance of close inspection," she said, "because every inch, line or brushstroke should not be taken for granted.”

On a recent Thursday, Julis and eight other students from the fall course “Renaissance Art and Architecture” examined four 16th-century architectural drawings and prints — all drawn from the collections of Princeton University Art Museum — as part of their weekly precept.

Mangone, second from left, and Yerkes, center, lead a precept discussion of four architectural drawings and engravings from the museum’s collections in the object-study room in Firestone Library.

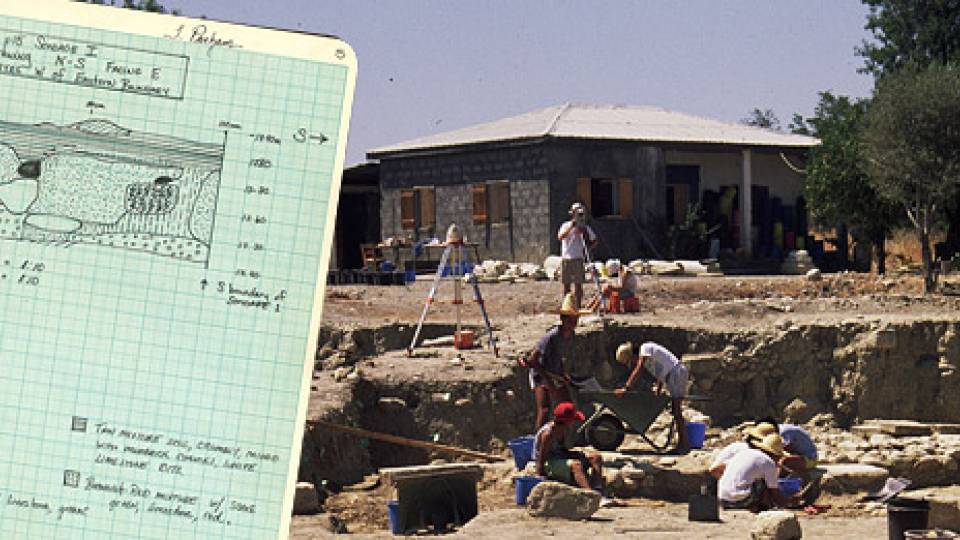

With collections exhibited here since the 18th century and a purpose-built museum on campus since 1890, Princeton students have long had the opportunity to learn about history, ideas, aesthetics and the human experience through the University’s vast collection, which began in the 1750s and now numbers more than 112,000 objects. But when the museum closed in 2020 to make way for the construction of a new museum designed by Sir David Adjaye, set to open in 2024, professors faced a dilemma: How to preserve the powerful experience of teaching with original artworks while the museum is closed?

“The use of two dedicated classrooms — one in Firestone Library and one off-site — is playing a crucial role in enabling faculty and students to continue engaging with original works of art during the construction of the new museum's building,” said Veronica White, curator of teaching and learning. White works with dozens of faculty members across departments each year to identify works of art that resonate with their curricula and reflect the diversity of the museum’s collections.

At Firestone, the new classroom is fitted with moveable wooden ledges that hang on a metal screen to display art. The off-site classroom contains a case with ledges and hanging screen for displaying art. Both are temperature- and humidity-controlled and furnished with long tables and comfortable chairs, and equipped with audiovisual technology. Two collections associates from the museum are dedicated to managing all curricular requests, and they pull art for each class and act as a proctor to aid faculty in the display and handling of each work utilized for teaching.

Learning the language of looking: ‘We give them a mystery and they write the story’

As Julis and her classmates gathered around the architectural works on paper in the Firestone Library classroom, Carolyn Yerkes, associate professor of art and archaeology, invited them to pick up a magnifying glass and take turns getting in close.

“My goal with every precept is to get the students to look carefully at what they see and learn to articulate their thoughts,” said Yerkes, who is co-teaching the course — a survey of three centuries of painting, sculpture, and architecture across northern and southern Europe — with Carolina Mangone, assistant professor of art and archaeology. “In our precepts, we never distribute information about the art in advance: Students have to think independently in the moment. We give them a mystery and they write the story. We give them the possibility of discovery.”

She continued: “When we take our students to study art directly in collections, we are teaching them how to look. That means first training their eyes and then figuring out how to describe what it is that they are seeing.”

Mangone and Yerkes also encourage students to make connections in precept with what they’ve learned in lecture.

"We use each object to explore larger ideas," Mangone said. "There are puzzling qualities students have to work through to find meaning and appreciate convergences. In tandem with meeting the intellectual challenge of looking, we urge students to embrace the sensual aspects of encountering objects — our embodied responses are a substantive part of the endeavor to make meaning."

The custom-outfitted classroom at Firestone allows this type of discovery to continue during construction of the art museum's new building — which will include a ground-floor Education Center with five object-study classrooms for instruction using artworks from the museum’s collections. A sixth object-study classroom will be located within the full-service Conservation Studio on the second floor — creating opportunities for students to learn about the art of conservation, including care for paintings, objects and works on paper.

Paper chase: Deciphering how Renaissance architects used drawings in their work

At Firestone, Yerkes focused the students’ attention on a study sheet from the workshop of the Italian architect Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, ca. 1530. It features eight pen-and-ink drawings on one page.

Simanga Ndhlovu, a member of the Class of 2022 and an architecture concentrator, examines a 16th-century architectural drawing with his classmate Ethan Reese, a member of the Class of 2023 who is concentrating in operations research and financial engineering.

One student noted that some of the drawings focused on perspective and others looked like architectural plans. He said one in the middle of the page looked like a castle, with formal geometry on the outside, like a fortress.

“Exactly,” Yerkes said. “Think of ‘Game of Thrones.’”

“For cannons,” the student said.

“Yes,” Yerkes said. “The cannons weigh several tons, so you have a raised earth bed to fire out but see the distinctive walls? They’re angled to deflect artillery fire.”

Indicating the organization of the drawings on the page, in three horizontal bands, she said: “Military architecture, sacred architecture and domestic architecture. “What’s the relationship here?”

“Might the architect be thinking about a master plan for a city?” one student suggested.

“Great point,” Yerkes said. “The archetypes of what you need in a city.”

The fine art of looking closely: 'It directly connects me to history'

When the group reached the last artwork, a 16th-century metal engraving of a Temple of Neptune in Rome, Yerkes invited the students to get in close with their magnifying glasses, their eyes literally two or three inches from the artwork, to examine and interpret minute details — from the varying widths of lines to writing the architect had included on the page.

“There is hardly any published scholarship on this print,” she told them. “There is no right or wrong answer. How does the print give you clues? The print says 1541. Do you think that’s the year the print was made and that this is an ancient temple? Or could 1541 be the year the temple in the print was built?”

She encouraged them to think about Mangone’s class lecture on Michelangelo and antiquity they had attended earlier that morning. During the lecture, students were exposed to ways that the makers of art and the patrons who displayed it shaped encounters with objects, often challenging the viewer's expectations. For example, Michelangelo's "Bacchus" (1496-97) — a statue originally displayed amidst fragmentary antiquities — blurred the boundaries between old and new, prompting viewers of that period to discern what was modern about this sculpture of a pagan god from antiquity.

“Giving a comprehensive lecture on Michelangelo is like trying to drink from a fire hydrant,” said Mangone. “My goal is not to discuss everything Michelangelo ever did but instead to introduce students to one thread of his complicated and rich sculptural practice — in this case, his transformation of antique paradigms and material remains to new ends in secular and sacred art.” Her current book project, "Michelangelo and the Art of Imperfection,” explores the artist’s unfinished sculpture.

In another precept for the class, students analyzed a Michelangelo drawing, circa 1530, from the museum's collections. Infrared reflectography has revealed a legible architectural black chalk drawing on the sheet’s verso: a preliminary design for one of Michelangelo’s late Roman projects, the Sforza Chapel in Santa Maria Maggiore. "Bust of a Youth and Caricature Head of an Old Man, Both in Left Profile," Michelangelo Buonarroti, Italian, 1475–1564, black chalk on tan laid paper. Princeton University Art Museum. Gift of Frank Jewett Mather Jr.

The art museum owns one Michelangelo drawing: In another precept for the class, students had analyzed the work. Dated 1530, it is a drawing of a bust of youth — but infrared reflectography reveals a legible architectural black chalk drawing on the sheet’s verso: a preliminary design for one of Michelangelo’s late Roman projects, the Sforza Chapel in Santa Maria Maggiore. Yerkes and Mangone often hold off telling students the work's authorship so that Michelangelo's fame doesn't overshadow the discussion; anonymous works frequently stimulate freer conversation, they said.

The Michelangelo drawing — like many artworks from the museum's collections — is stored in an archival box called a "solander" box. Works on paper and photographs are typically matted as an extra step of protection for handling the art. When the art is in storage, "interleaving" — a piece of archival glassine or unbuffered archival paper — is placed inside each mat to protect the surface of the artwork. With freshly cleaned hands, the collections associate removes the interleaving and carefully places the artwork on the display ledge or table for students to view.

Stepping in closer to the engraving of the Temple of Neptune, one student observed: “I don’t think there would be a pagan temple in Rome, the heart of Christianity, in 1541.”

Another student also expressed his doubts that the temple was from antiquity. “If it were, it would look worn, as in ruins,” he said. “The building in this print is really detailed with an implied completeness.”

After they’d analyzed other details, from Latin words and numbers to the initials “J.B.” engraved in one spot, Yerkes told the group: “Congratulations. We have just ‘read’ a 16th-century architectural print.”

Julis, who is concentrating in art and archaeology, said the experience of interpreting an unpublished artwork was fascinating. “When Professor Yerkes looked at us and said, “Your guess is as good as mine,” I was reminded that anyone, from professor to student, can make contributions and interventions, and that’s what’s so exciting.”

Nadir Alkhabbaz, a member of the Class of 2022 who is concentrating in architecture, said he looked forward to viewing the artworks in every precept. “It is a great privilege and blessing to be able to examine works from the Princeton University Art Museum’s collection that have their roots in the Renaissance; it directly connects me to history,” he said.

Katie Hameetman, a classics concentrator and member of the Class of 2023, said she appreciated the opportunity for the free exchange of ideas. “As we focused on specific examples of architectural depictions, being able to discuss our observations with each other — whether concerning a piece in isolation or in its relationship to the pieces shown alongside it — allowed us to construct a more complete analysis than we would have done individually.”

Object lessons: ‘Encountering art is its own form of human experience’

This is the third time Yerkes and Mangone have co-taught the course, for which they alternate giving lectures and lead separate precept groups. Mangone has also taught the course independently twice before — including via Zoom during lockdown, when she was still able to create direct encounters for the students with original art from the museum by using its state-of-the-art digital resources. In one online precept, students used materials they had at hand to copy two digitized versions of Renaissance figure drawings made with pen-and-ink on paper. The goal, she said, was to immerse them in a pedagogical practice typical of early modern workshops. "By effectively producing an art object in its own right, this activity bridged two gaps: between the past and the present, and between the digitized artifact and its material iteration by each student."

Notwithstanding the success of activities like these using digital resources, Mangone is thrilled once again to be studying objects firsthand with students and alongside her colleague. "The best course cultivates an environment of shared exploration and discovery among classmates and professors alike," she said. "That prospect multiplies in a co-taught setting."

"I think teaching together helps the students to see where our interpretations converge and where they diverge,” said Yerkes. “We hope that they learn by listening to us that there are a lot of approaches one can take to the study of the past.”

She added: “Carolina is the most fluid lecturer I have ever seen and every time she speaks about art, she gets me to see something I never noticed before — even if the subject is a work I've spent years looking at and discussing.”

“Carolyn makes the study of architecture come alive,” Mangone said. “I think co-teaching underscores the reality that learning is invariably collaborative — as much for the professors as the students — and that plurality cultivates meaningful engagement.”

Yerkes said that she hopes students, no matter what their major, will gain a key takeaway from the course. “Encountering art is its own form of human experience, one that helps us understand the past, order our thoughts and give our lives meaning.”

‘Extraordinary synergies’: Teaching with art across academic disciplines

With the closure of the art museum, Yerkes and Mangone had to reconfigure most of their precepts, a process they worked on with White. “This meant diving back into the collections to rewrite our lesson plans around new objects — which is always fun, because we get to see new art,” Yerkes said.

This fall, courses ranging from “Muertos: Art and Mortality in Mexico” to “Seeing Health: Medicine, Literature and the Visual Arts” were taught using works from the museum's collections ranging from Rembrandt etchings to Maya ceramic vessels.

For a junior seminar in critical writing in the English department, taught by Sarah Anderson, lecturer in English, White carefully selected works from the collections for the seminar’s theme: “Borderlines.”

“The week the students began reading Virginia Woolf's ‘Mrs. Dalloway,’” White said, “Sarah and I thought about the novel's pathbreaking stream-of-consciousness and its modeling of female subjectivity. We selected a group of Surrealist prints, drawings and photographs for the students to analyze and discuss. In short written essays, the students reflected upon the sorts of symbols and artistic processes we had observed together, comparing one work of art to another.”

William Noel, the John T. Maltsberger III '55 Associate University Librarian for Special Collections, is excited about another silver lining as the museum and Princeton University Library (PUL) work in tandem to support teaching and learning during the construction of the new museum: Students can also view rare books and artwork together at the library. “This is a natural and happy collaboration, as many works of art from the museum have extraordinary synergies with PUL’s Special Collections,” Noel said. “During this time, for example, students can see woodcuts from the 15th century alongside 15th-century books.”

He noted another example: “Piranesi on the Page,” a recent exhibition at Firestone Library, co-curated by Yerkes, the author of “Piranesi Unbound” (Princeton University Press, 2019). Funded in part by the Humanities Council's Magic Project, the exhibition captured how the foremost printmaker in 18th-century Europe made the book the center of his artistic production. “Visitors were able to see masterworks by Piranesi from the library’s holdings side by side with stones and gems from the museum, and from which Piranesi took inspiration,” Noel said.

While the current object-study arrangements at Firestone Library are temporary, Noel said permanent bridges are being built for the future. “In the years ahead, faculty and students can expect to see more close collaboration between Princeton University Library and the museum,” he said.