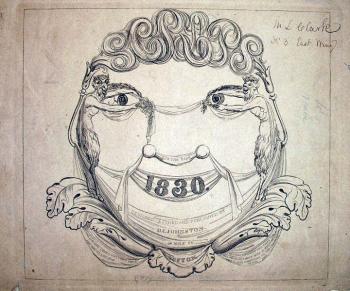

Philip Ashton Rollins (1869-1950) was born in Somersworth, New Hampshire, but spent a good deal of his youth in the American West, where he developed a fascination with its culture and lifestyle. Rollins graduated from Princeton University in 1889 and established a law practice in New York City. His continuing interest in all things Western led him to research and publish The Cowboy, An Unconventional History of Civilization on the Old-Time Cattle Range in 1933 and Jinglebob in 1928, among many other titles. He was also a benefactor of Princeton, serving as the chairman and co-founder of the Friends of the Princeton Library in 1930.

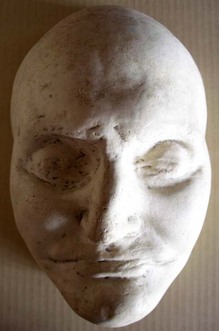

In 1947, Rollins and his wife presented the Princeton Library with a valuable collection of Western Americana, consisting of books and manuscripts on all aspect of Western life and culture. In addition, Rollins presented the library with his bronze relief portrait (above) created by Gutzon Borglum (1867-1941).

The American sculptor of Scandinavian descent is best known for his colossal sculptures, particularly the presidential portraits on Mount Rushmore in South Dakota. Borglum’s works held in Princeton University collections are somewhat smaller but no less beautiful.

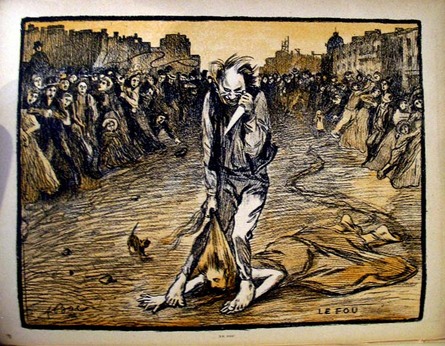

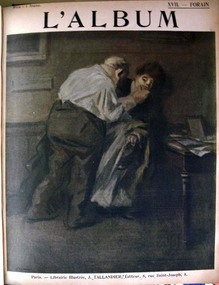

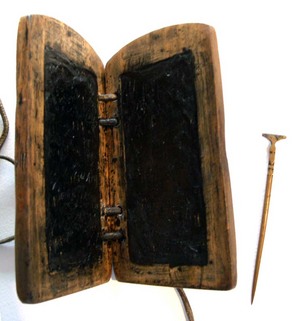

Borglum trained in Paris at the Académie Julian, where he formed a close relationship with the sculptor Auguste Rodin. After a stay in London, Borglum settled in New York City around 1901 and completed a series of small bronze figures including John Ruskin (left).

Our graphic arts collection also holds an untitled ink drawing by Borglum of a cowboy riding a horse on a desolate plane dated 1890. Borglum sailed to Europe on the Bourgogne in 1890 and the drawing includes the note, ‘On ‘La Bourgogne’ Sept. 1890. (Graphic Arts collection GA 2006.02368)

Four articles on Rollins and his collection are published in the Princeton University Library Chronicle IX, 4 (June 1948), pp 177-210.

See also the Philip Ashton Rollins manuscript collection WC001.

Recent Comments