Class Notes - December 15, 1999

Class notes features

From the Archives

Where did these undergraduates find a bicycle built for five? According

to a caption attached to this March 1956 photograph, the men (from left)

John Dennis '58, Joe Nye '58, Hugh Fairman '58, John Sawhill '58, and Bill

Carruthers '58, were training for a 150-mile ride to Vassar College in May.

Perhaps one of our readers knows more.

Where did these undergraduates find a bicycle built for five? According

to a caption attached to this March 1956 photograph, the men (from left)

John Dennis '58, Joe Nye '58, Hugh Fairman '58, John Sawhill '58, and Bill

Carruthers '58, were training for a 150-mile ride to Vassar College in May.

Perhaps one of our readers knows more.

The Avon lady...lesson on Washington

Alumni trustee Andrea Jung '79 has broken through the glass ceiling

and become the ultimate Avon lady with her promotion to chief executive

officer in November. Formerly Avon's president and chief operating officer,

Jung is the fourth woman to be appointed chief executive of a Fortune 500

company. For the past two years, Jung was named one of Fortune's "50

Most Powerful Women in American Business." Her promotion came on the

heals of the sudden retirement of CEO Charles R. Perrin. Since joining the

company in 1994 as a marketing executive, Jung is credited with updating

the company's image, merchandise, and packaging.

Alumni trustee Andrea Jung '79 has broken through the glass ceiling

and become the ultimate Avon lady with her promotion to chief executive

officer in November. Formerly Avon's president and chief operating officer,

Jung is the fourth woman to be appointed chief executive of a Fortune 500

company. For the past two years, Jung was named one of Fortune's "50

Most Powerful Women in American Business." Her promotion came on the

heals of the sudden retirement of CEO Charles R. Perrin. Since joining the

company in 1994 as a marketing executive, Jung is credited with updating

the company's image, merchandise, and packaging.

Robert B. Gibby, sr. '36's passion for George Washington has fueled an

effort to educate fifth-graders around the country about our first president.

Through a program organized by the Mount Vernon Ladies Association, teachers

in 30 states have received materials for a biography lesson on Washington,

including a half-hour videotape, The Life of George Washington, which illustrates

events in Washington's life using historical prints from Mount Vernon. Gibby

hopes to place the biography lesson in every school in the U.S. The Class

of 1936, whose honorary members include George Washington, has funded the

program in the state of Washington.

Third time around Nassau Hall Pat

Cronin '47 returns to Princeton at age 73

At age 73, Robert Fancis Partick Cronin '47 of Montreux, Switzerland,

has enrolled in Princeton for the third time and hopes to get a degree at

last. Pat Cronin matriculated the first time in 1943, at the age of 17.

At age 73, Robert Fancis Partick Cronin '47 of Montreux, Switzerland,

has enrolled in Princeton for the third time and hopes to get a degree at

last. Pat Cronin matriculated the first time in 1943, at the age of 17.

After two semesters, he left for military service, first in Canada, then

in Great Britain. (He was born in London, the son of A. J. Cronin, who wrote

the bestsellers The Stars Look Down and The Citadel.) In January 1948, Cronin

re-enrolled at Princeton and finished two more years before he left to go

to medical school at McGill University in Montreal.

Afterward, he kept busy with a career that included teaching, research

on coronary disease, practicing cardiology, and serving as dean of the McGill

medical school for five years and as a consultant and adviser on health

care in developing countries.

Cronin and his wife, both ardent skiers, moved to Montreux in 1980, but

he continued his work as a health-care consultant. "I got bored when

I retired last year and decided to see if I could come back to Princeton,"

he said. He was advised and encouraged by his classmate George Eggers, who

returned in 1978 at the age of 52 and got his degree two years later.

The university administration agreed to let him earn his degree if he

came for one semester, took three courses, and wrote his senior thesis.

Eggers found him a one-bedroom apartment at 32 Chambers Street, a location

that allows Cronin to walk everywhere. For exercise he walks to a local

grocery and back.

One of Cronin's classes is a psychology course, The Brain: A User's Guide,

taught by Barry Jacobs, director of the Program in Neuroscience and an expert

on hallucinogenic drugs. "He's wonderful," said Cronin. One of

the videos shown in precepts featured an expert in Parkinson's disease who

was a good friend of Cronin's in Montreal. Reinier Leushuis, a Dutch graduate

student instructor, teaches the small French class he's taking. "He

gives us texts from Voltaire to Sartre," Pat said. The class is taught

entirely in French, easy for Pat who took French at Princeton, spent years

in bilingual Montreal, and lives in French-speaking Montreux. His third

course, about the history of medicine in the West, is taught by Gerald Geison.

Things are different the third time around. Cronin says that, when he

first attended Princeton, "precepts had only five or six people in

them," he said. Today, he says, the precepts may have twice that number

of students, and reading assignments are heavy, 200 pages a week for each

course. He finds himself working until midnight most nights.

He stays in touch with his wife with daily e-mails and frequent phone

calls. The Cronins have a small apartment in Naples, Florida, and they planned

to fly there for fall break.

-Ann Waldron

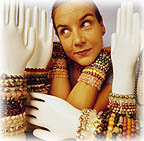

To bead or not to bead

Zoe Metro (Heather Aponick '91) designs accessories for the Crystal

Age

By now chances are you've seen powerbead bracelets because you can't

miss them. The fashion hit of the season, they (and their imitators) seem

to be sold everywhere, from high-end boutiques to mall kiosks, and people

are buying them like crazy. The bracelets of semiprecious stones appeal

to both genders and to multiple generations because of the promises they

make: Health. Wealth. Love. Harmony. Strength. PMS relief. Who wouldn't

want it all?

By now chances are you've seen powerbead bracelets because you can't

miss them. The fashion hit of the season, they (and their imitators) seem

to be sold everywhere, from high-end boutiques to mall kiosks, and people

are buying them like crazy. The bracelets of semiprecious stones appeal

to both genders and to multiple generations because of the promises they

make: Health. Wealth. Love. Harmony. Strength. PMS relief. Who wouldn't

want it all?

These and many other enticing spiritual and material attributes can be

yours for about $25 per promise, courtesy of the healing energies inherent

in the bracelets, which are designed and manufactured by Zoe Metro (the

Princeton graduate formerly known as Heather Aponick '91). Metro's powerbead

bracelets are made of stones such as turquoise (health) and tiger's-eye

(creativity). To date, powerbeads have adorned the wrists and augmented

the psyches of such trendsetters as Madonna, Natalie Portman, and Ricky

Martin, according to substantial media coverage garnered in national publications.

Still a doubter? Metro wore a bracelet of aventurine (success) after her previous

design business, the eponymous Zoe Metro, went bust last November, due to an

unfortunate choice of business partners. [Metro plans to launch a new jewelry

line in May 2010, having married and given birth to a son, Jed.] Within six weeks

she was up and running again, with the Manhattan-based company Stella Pace (Italian

for "star of peace"). Then there's the month she wore mother-of-pearl

(money) and sales doubled. "I couldn't go a day without them," says

Metro, who at the time of this interview was sporting the millennium powerbead

for good luck teamed with the Feng Shui serenity beads.

Then again, some might attribute Metro's success not to the mystical

powers of rocks but to a winning combination of talent and savvy business

sense, honed by a rich and varied career. She started out in advertising,

with stints in Paris and Prague. A segue into marketing began when she returned

to the United States in 1994 and worked for Spin magazine and then at Hearst

Magazines. But thoughts of establishing her own business mingled with thoughts

of fashion, and she spent a year taking night classes at the Fashion Institute

of Technology, where she failed sewing three times.

Although she has yet to sew an acceptable Peter Pan collar, she knows

how to package her ideas. Nevertheless, Metro is quick to give credit where

it's due, and attributes the powerbead craze to the power of the stones

rather than citing market studies or fashion know-how. She admits that "this

whole phenomenon is beyond my wildest dreams."

But that doesn't mean she's done dreaming. She has plans for Stella Pace,

established January 1999. The company's products, which also include chokers,

handbags, and lariat necklaces, are carried in 300 stores. Metro intends

to create clothing that will outfit "the girl who works," and

envisions quality pieces with only one form for each function: "good

pieces that all go together and build a collection." For the immediate

future, she is developing a pair of leather pants and a dress shirt, each

of which have small crystals sewn in patterns that mimic the way in which

crystals are aligned on the body during healing ceremonies.

All of her designs are simple, streamlined and have an associated spiritual

meaning. For example, all of the bags in the Stella Pace line have a silver

lining. Think about it: If you were buying an evening bag, would you rather

have a cute little bag or a cute little bag with a silver lining and a handle

beaded with stones reputed to have healing powers?

Metro credits her academic background at Princeton as an art history

major as very important to her present career. She cites Professor Robert

Bagley, with whom she studied ancient Chinese art, as a significant influence.

At Zoe Metro, which she launched in August 1997, Metro borrowed from ancient

Chinese traditions with handbags that incorporated red silk linings (symbolic

of good luck) and reproductions of 15th-century Chinese coins (said to attract

money and peace of mind). She wrote her thesis on the tapestries of the

ancient Peruvian community of Paracas.

Yet, although her academic background, business training, and fashion

expertise all play into her current endeavors, her philosophy of design

is stunningly simple. She designs mostly at night, when it's quiet and she

has the time. As for where she gets her ideas, her vision is unencumbered

by today's fickle world of fashion trends, despite her ability to create

them: "I only design things that I would want," she explains.

-Andrea Gollin '88

Clueless? Not him

Martin Schneider '90 finds constructing crossword puzzles all-consuming

While riding the subway one day, Martin Schneider '90 saw a woman filling

in the blanks of The New York Times crossword puzzle. Recognizing it as

one of his creations, he approached her. "I said, 'That's my puzzle!'

" Schneider recalls. "She said, 'No, it's mine!' She thought I

was trying to pick her up."

While riding the subway one day, Martin Schneider '90 saw a woman filling

in the blanks of The New York Times crossword puzzle. Recognizing it as

one of his creations, he approached her. "I said, 'That's my puzzle!'

" Schneider recalls. "She said, 'No, it's mine!' She thought I

was trying to pick her up."

Schneider has had 10 puzzles published in the Times-including four in

the coveted Sunday magazine-and has had seven rejected (including one he

thought was particularly good, which included the quip "an ambidextrous

rower is very comfortable using either oar").

To build a puzzle, first Schneider chooses a theme-the quip or pattern

or "trick" found in most larger puzzles-and its related clues.

Once he fits those in the confines of his grid, he fills in the remaining

spaces with words not essential to the puzzle's theme; they become the glue

that holds the whole thing together. Clues to those words are written after

the puzzle is constructed.

Constructing is all-consuming, Schneider says. "The last one took

100 hours." At $75 per weekday puzzle and $350 per Sunday puzzle, that

comes to significantly below the minimum wage-and means Schneider isn't

likely to become a full-time crossword constructor any time soon.

But that's ok, because Schneider loves his day job. A copywriter for

the New York advertising firm of Warwick Baker O'Neill, he figures he's

pretty much found his calling. "I spend all day trying to come up with

ways to entertain, amuse, or move people," Schneider says. "I

sit there with a pen on the couch and stare at the ceiling."

He discovered copywriting while attending Columbia business school, where

he soon realized he had no desire to be an investment banker or a management

consultant. Instead, he took an eclectic mix of classes at Columbia, from

literary criticism to linguistics. And when he decided to give copywriting

a try, he added a class at the School of Visual Arts. The system of critiquing

work-students create mock ads, and listen to everyone else's comments-means

"you quickly find out if you have talent," Schneider says. "I

knew immediately that I loved it."

Schneider spent six months putting together a portfolio of ads after

graduating from Columbia. One, an ad for the USS Intrepid aircraft carrier,

permanently anchored on the Hudson River, said "Yes, you can touch

the guns. No, you can't shell New Jersey."

"The goal is to create a 'stopper,' " Schneider says. "You

see people reading a magazine: they flip, flip, flip, and then suddenly

they stop. Something about that ad makes them pay attention." After

finishing his portfolio, he started interviewing, and landed his current

job.

Schneider can see a connection between copywriting, crossword puzzle

construction, and his work as a philosophy major at Princeton, where he

wrote his thesis on the philosophical ramifications of Einstein's relativity

theory.

In all of them, he says, "you spend a lot of time thinking about

relatively few words. There's no massive analysis of data."

Philosophy major to B-school student to part-time crossword puzzle maven

and full-time copywriter? It's not a linear career path. But like the words

in one of Schneider's puzzle creations, it all somehow fits together.

-Katherine Hobson '94

GO TO

the Table of Contents of the current issue

GO TO

PAW's home page

paw@princeton.edu

Where did these undergraduates find a bicycle built for five? According

to a caption attached to this March 1956 photograph, the men (from left)

John Dennis '58, Joe Nye '58, Hugh Fairman '58, John Sawhill '58, and Bill

Carruthers '58, were training for a 150-mile ride to Vassar College in May.

Perhaps one of our readers knows more.

Where did these undergraduates find a bicycle built for five? According

to a caption attached to this March 1956 photograph, the men (from left)

John Dennis '58, Joe Nye '58, Hugh Fairman '58, John Sawhill '58, and Bill

Carruthers '58, were training for a 150-mile ride to Vassar College in May.

Perhaps one of our readers knows more. Alumni trustee Andrea Jung '79 has broken through the glass ceiling

and become the ultimate Avon lady with her promotion to chief executive

officer in November. Formerly Avon's president and chief operating officer,

Jung is the fourth woman to be appointed chief executive of a Fortune 500

company. For the past two years, Jung was named one of Fortune's "50

Most Powerful Women in American Business." Her promotion came on the

heals of the sudden retirement of CEO Charles R. Perrin. Since joining the

company in 1994 as a marketing executive, Jung is credited with updating

the company's image, merchandise, and packaging.

Alumni trustee Andrea Jung '79 has broken through the glass ceiling

and become the ultimate Avon lady with her promotion to chief executive

officer in November. Formerly Avon's president and chief operating officer,

Jung is the fourth woman to be appointed chief executive of a Fortune 500

company. For the past two years, Jung was named one of Fortune's "50

Most Powerful Women in American Business." Her promotion came on the

heals of the sudden retirement of CEO Charles R. Perrin. Since joining the

company in 1994 as a marketing executive, Jung is credited with updating

the company's image, merchandise, and packaging. At age 73, Robert Fancis Partick Cronin '47 of Montreux, Switzerland,

has enrolled in Princeton for the third time and hopes to get a degree at

last. Pat Cronin matriculated the first time in 1943, at the age of 17.

At age 73, Robert Fancis Partick Cronin '47 of Montreux, Switzerland,

has enrolled in Princeton for the third time and hopes to get a degree at

last. Pat Cronin matriculated the first time in 1943, at the age of 17. By now chances are you've seen powerbead bracelets because you can't

miss them. The fashion hit of the season, they (and their imitators) seem

to be sold everywhere, from high-end boutiques to mall kiosks, and people

are buying them like crazy. The bracelets of semiprecious stones appeal

to both genders and to multiple generations because of the promises they

make: Health. Wealth. Love. Harmony. Strength. PMS relief. Who wouldn't

want it all?

By now chances are you've seen powerbead bracelets because you can't

miss them. The fashion hit of the season, they (and their imitators) seem

to be sold everywhere, from high-end boutiques to mall kiosks, and people

are buying them like crazy. The bracelets of semiprecious stones appeal

to both genders and to multiple generations because of the promises they

make: Health. Wealth. Love. Harmony. Strength. PMS relief. Who wouldn't

want it all? While riding the subway one day, Martin Schneider '90 saw a woman filling

in the blanks of The New York Times crossword puzzle. Recognizing it as

one of his creations, he approached her. "I said, 'That's my puzzle!'

" Schneider recalls. "She said, 'No, it's mine!' She thought I

was trying to pick her up."

While riding the subway one day, Martin Schneider '90 saw a woman filling

in the blanks of The New York Times crossword puzzle. Recognizing it as

one of his creations, he approached her. "I said, 'That's my puzzle!'

" Schneider recalls. "She said, 'No, it's mine!' She thought I

was trying to pick her up."