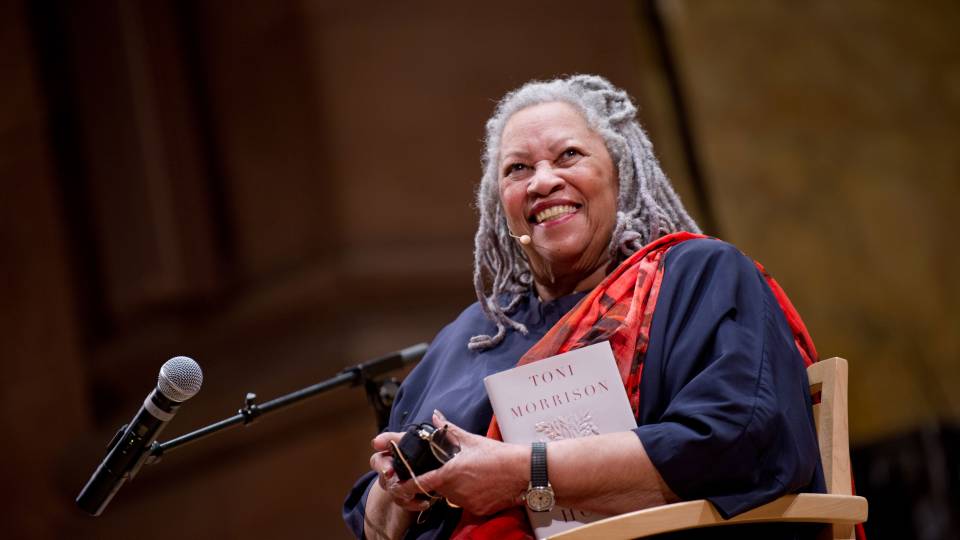

"Sites of Memory: A Symposium on Toni Morrison and the Archive" gathered leading Morrison scholars, writers and artists for rich insights, inspiring conversations, performances and more. Pictured: Jeannine Cook, owner of Harriett's Bookshop in Philadelphia and Ida's Bookshop in Collingswood, New Jersey, greets attendees in the Morrison-inspired "theatrical set" she designed for her pop-up shop at the symposium.

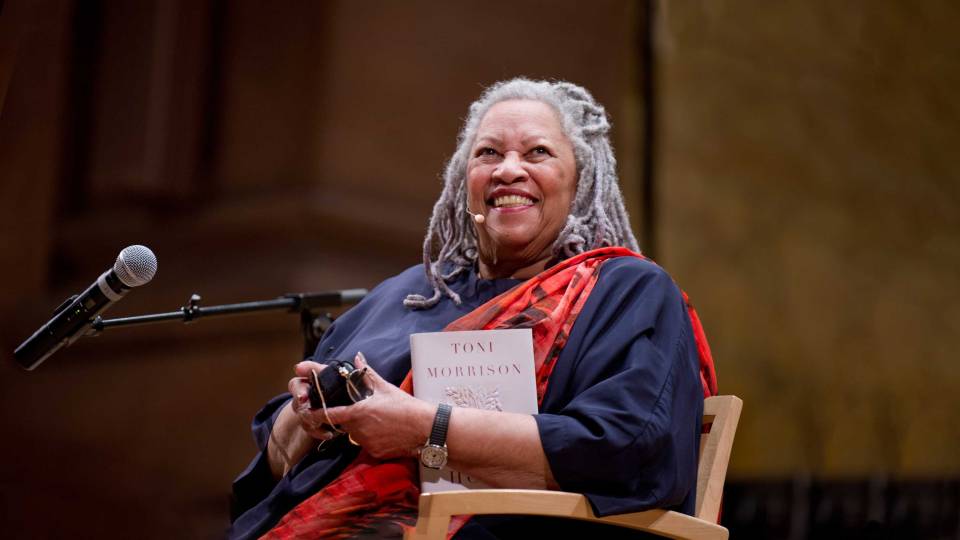

As the lights dimmed in the Wallace Theater on the opening evening of “Sites of Memory: A Symposium on Toni Morrison and the Archive,” a hush fell over the audience as a warmly magisterial voice, instantly recognizable to all, began to speak in the near darkness:

“Art invites us to take the journey from data to information, to knowledge, to wisdom. Artists make language, images, sounds to bear witness, to shape beauty, and to comprehend. My faith in their work exceeds my admiration for any other discourse. Such conversation with the public and among various genres of art and scholarship — this conversation is vital to our understanding of what it means to be human.”

As the lights came up, there she was, the late Toni Morrison, Nobel laureate, on-screen in a clip from the documentary “The Foreigner’s Home,” which captures reflections from her 2006 residency at the Louvre.

Morrison’s wise words created an auspicious welcome to the landmark symposium, which took place at Princeton March 23-25. More than 150 scholars, artists, students and others from around the country attended.

Illuminating the scope and impact of Morrison’s archive — housed in Princeton University Library — on past, present and future generations of scholars, students and artists, the symposium opened with a keynote address by the eminent Haitian American writer Edwidge Danticat. Five lively panels with leading Morrison scholars, as well as writers, filmmakers and artists, gathered rich insights and conducted inspiring conversations. The event concluded with a dynamic plenary conversation with poet and scholar Evie Shockley and artist Alison Saar, whose exhibition “Cycle of Creativity: Alison Saar and the Toni Morrison Papers” is on view through July 9 at Art@Bainbridge.

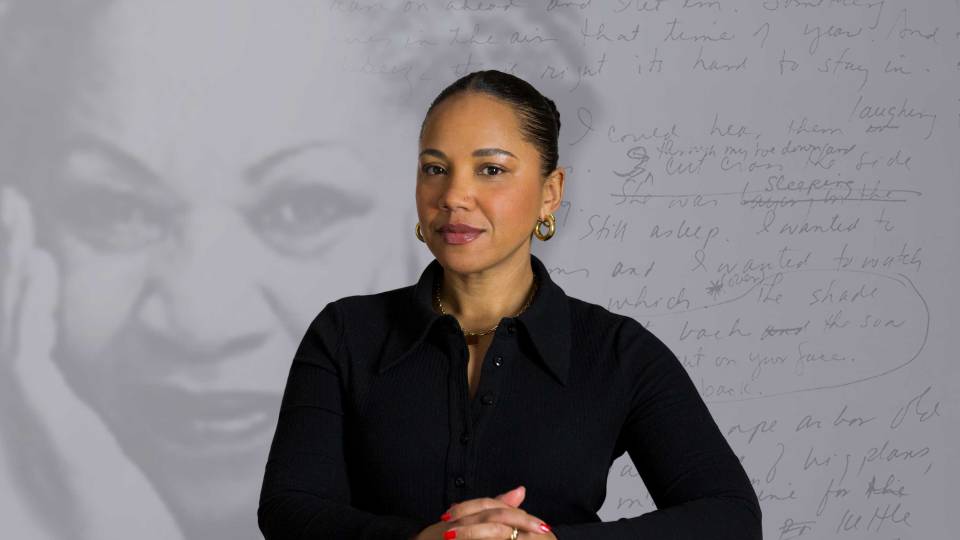

The symposium, co-organized by Autumn Womack, associate professor of African American studies and English, and Kinohi Nishikawa, associate professor of English and African American studies, is part of a campus-wide exploration of Morrison's creative process; its centerpiece is the exhibition “Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory” at Princeton University Library, curated by Womack, on view through June 4. Morrison, the Robert F. Goheen Professor in the Humanities, Emeritus, taught at Princeton from 1989 to 2006 and died at in 2019 at 88 years old.

Primarily funded through a Humanities Council Magic Project, and co-sponsored by the Department of African American Studies and the Department of English, the symposium coincided with a newly commissioned theater work, “The Toni Morrison Project,” at McCarter Theatre Center and the Toni Morrison Lectures with Farah J. Griffin, presented March 28-30 by the Department of African American Studies. On April 12, Princeton University Concerts will present a newly commissioned program, also inspired by the Morrison archive, by three-time Grammy Award-winning jazz vocalist and composer Cecile McLorin Salvant at Richardson Auditorium.

‘We let her work guide us’: Edwidge Danticat on Morrison

"She is present in all of us gathering here tonight and in her archives,” said writer Edwidge Danticat in her keynote speech, reflecting on the myriad ways Morrison's archive inspires readers, scholars and artists.

“Memory is the great bridge between the past and the present,” said Womack, introducing keynote speaker Edwidge Danticat and articulating a theme that would be explored throughout the symposium: the vital role that the archive played in Morrison’s creative process and the myriad ways memory interplays with the archive in creating new work across genres.

Sprinkling a little water from her water bottle on the floral arrangement in front of the podium and uttering a Haitian blessing, Danticat exclaimed, “Here’s to the next generation of Morrison readers.”

She recalled meeting Morrison when she came to Princeton 15 years ago to deliver the second annual Toni Morrison Lectures. “I spent half a year writing those talks because I knew Ms. Morrison was going to be in the front row and I was terrified,” she said.

She needn’t have been. At the dinner before the talk, Danticat confided to Morrison she felt guilty because she’d forgotten that evening was her daughter Mira’s third birthday. By the end of the dinner, a cupcake and a candle to blow out appeared for Mira.

Danticat, the author of “Breath, Eyes, Memory,” “Krik? Krak!,” “The Dew Breaker,” “Claire of the Sea Light" and other acclaimed works as well as books for young adults and children, said the power of memory speaks strongly to her. “Growing up in Haiti and Brooklyn my mother would say we have three deaths: when we stop breathing, when we’re put in the ground, and when no one calls our names anymore or remembers us at all. There is no risk of this with Ms. Morrison. We gather in places like this and we let her work guide us. She is present in all of us gathering here tonight and in her archives.”

Morrison’s work takes the reader on endless journeys, Danticat said. “You read it. Take a breather. You rock yourself. You walk away. And then you go back and open that book again… . I think of every story as a necklace of stories — one story leads to another story.”

Danticat, who previously worked for director Jonathan Demme, recalled one of Morrison’s visits to the set of the film “Beloved,” which Demme directed. They were shooting the carnival scene and the set was teeming with hundreds of people. “Everyone on that set had been a student of hers in some way: knew the woman, knew the work, knew its power. And we were on set with her beautiful mind, her dancing mind.”

“Coming to this event, I was reminded why I was so drawn to Morrison and Danticat's work, to my English classes, to books,” said 2018 Princeton graduate Natalie Tung, co-founder and executive director of HomeWorks Trenton, whose thesis was an analysis of “Beloved” with Womack as her adviser.

“I have been thinking a lot about the word ‘legacy’ lately,” Tung said. “Ms. Danticat used Ms. Morrison's work to give me a new understanding around this word, reminding me that in order to know who we are and where we are going, we need to ground ourselves with our ancestors and reckon with our own histories.”

‘Curated conversations’ explore the infinite possibilities of the archive

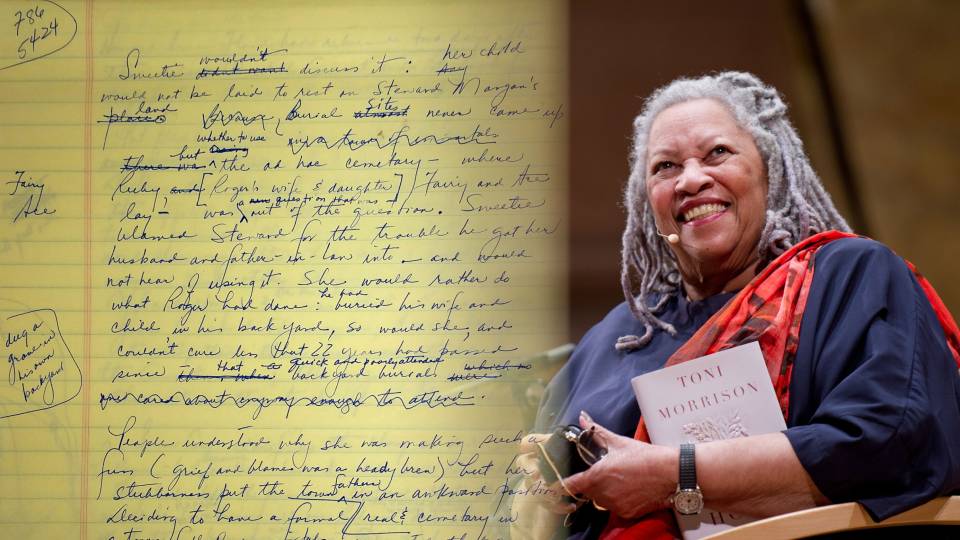

Welcoming the audience on day two, Womack heralded the archive as “the site where we see Morrison practicing her ‘habit of art,’ it is where we see glimpses of collaboration. It is also the site where memory and imagination confront each other. It reminds us of how expansive Morrison’s own thinking was and, in turn, how expansive our thinking about her must be,” she said.

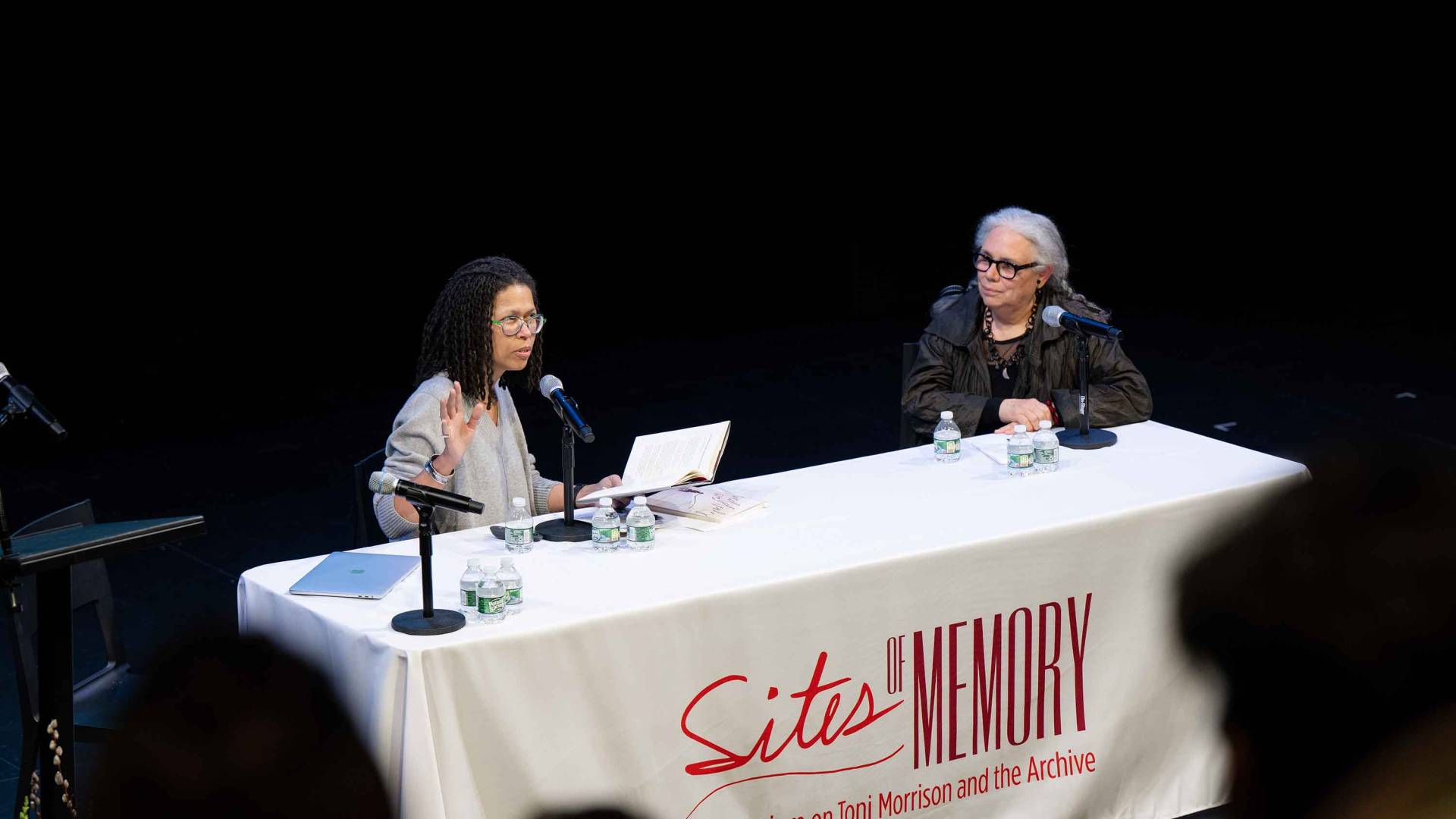

Symposium co-organizers Autumn Womack (left), associate professor of African American studies and English, and Kinohi Nishikawa (right), associate professor of English and African American studies, greet the audience, introducing a series of "curated conversations" to celebrate and explore the impact and possibilities of the Morrison archive — "the site where memory and imagination confront each other," Womack said.

“In the Morrisonian spirit of collaboration and innovation,” Nishikawa told the audience, they could look forward to five “curated conversations” in lieu of panels. “What you’ll see emerge is a dynamic and diverse set of engagements with Toni Morrison, but also scholars, artists and writers deeply engaged with one another,” he said.

The conversations explored Morrison’s friendships with other Black feminist authors, her modes of looking at Black life, her connections to classicism, and how the archive is inspiring visual and performing artists as well as poets and novelists.

Jennifer DeVere Brody, professor of theater and performance studies at Stanford University, grew up in the Witherspoon-Jackson neighborhood in Princeton. As part of the “Looking After Morrison” conversation, she drew on the way Morrison “provided a blueprint for her writing, mapping the architectural space of her own devising,” and described an unremarkable but historically significant house at 110 Witherspoon Street — the birthplace of Paul Robeson. It was first a grocery store, then a school for Black children, then a rooming house — “a southern refuge,” she said, where women gathered to sew and connect. Gladys Taylor, who lived there for 45 years and was friends with and modiste for Brody's mother, sewed Brody's third-grade graduation dress from Miss Mason's School. Today, Kevin Wilkes, a 1983 Princeton graduate, is converting the house to a museum and mixed-use building, to be called the Paul Robeson House.

Brody called this “living museum to recognize the Black communities” of Princeton both a kind of literal archive — the construction has unearthed socks, letters, photos, bullets and other items — as well as figurative one: a symbolic reminder of the diversity not always accounted for in the town’s or University’s history.

Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, associate professor at Georgetown University, spoke of “the worlds of Black girl intimacy” in Morrison’s novels, including the secret language “hidagay” that 12-year-old Christine and 11-year-old Heed develop in “Love” — “their private code for intimacy, gossip, a way to explore themselves and the world around them.” Sullivan said this is one of the many reasons she loves to listen to Morrison’s audiobooks, so she can hear Morrison herself bring this language — and the friendship it celebrates — to life. “This is the genius of Morrison as storyteller,” Sullivan said.

One of the attendees, Al-Yasha Williams, an associate professor of philosophy and religious studies at Spelman College, said she felt steeped in the “creative intellect” of all the presenters. “We all know the depth of Toni Morrison‘s fiction and the breath of her intellectual capacity, but rarely are we able to glimpse the process by which her works come into manifestation.”

Williams said it was helpful to learn how archives inform scholarship and creative work in combination. She and her colleague, assistant professor of dance and choreographer T. Lang, are on campus for two weeks as part of a two-year project supported by the Princeton Alliance for Collaborative Research and Innovation (PACRI), a series of research collaborations between Princeton University faculty and their peers at historically Black colleges and universities.

They are collaborating with Brian Herrera, associate professor of theater in the Lewis Center for the Arts, and Chesney Snow, lecturer in theater, and their students, drawing on the Audre Lorde archives at Spelman College. An exchange visit to Spelman by the Princeton collaborators is planned for spring 2024.

Later on the second day’s program, in the conversation “Writing the Archive,” Imani Perry, Princeton’s Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies, commented that, “Archiving is the work of curating the raw stuff of life.”

One of Perry’s favorite aspects of the archive are Morrison’s choices that reflect specific moments in history — such as her decision to have a song, Lloyd Price’s 1952 “Lawdy Miss Clawdy,” playing on the car radio as Frank in “Home” is threatening the driver to drive faster. “I hear the older folks in my own family and there’s an affective register of a body of sound, which is meaningful in the sense of a collective space,” Perry said. “This is quite potent; there’s more than one kind of archive at work.”

‘Nobody knew for what’: Creating a clearing for creativity

Introducing the conversations on the ways the archive engenders new work, Nishikawa noted the “leaps of speculation, inspiration and vibration that Morrison makes possible — the world-building capacities of the imagination.”

The conversation titled “‘nobody knew for what’: Toni Morrison’s Clearings of Earth for Art and Art for Earth,” a reference to the clearing in “Beloved” that flourishes as a place of Black gathering, featured performances by four art-makers, including readings by poets Adjua Gargi Nzinga Greaves and fahima ife.

One of the "curated conversations" featured performances, readings and reflections by four art-makers whose work is inspired by the Morrison archive: (from left) interdisciplinary artist and filmmaker Ja’Tovia Gary, poets Adjua Gargi Nzinga Greaves and fahima ife, and interdisciplinary artist JJJJJerome Ellis.

Ja’Tovia Gary shared clips from her film “Quiet As It’s Kept,” inspired by “The Bluest Eye,” which she read in her teens growing up in a working-class family in Texas. The film is a bricolage of animations accompanied by Morrison’s recording of the opening lines of the novel, a clip from a Morrison interview in which she famously says, “An unhappy childhood makes a good writer,” footage of the Haitian-American dancer Bianca Melidor and the artist herself.

JJJJJerome Ellis, a self-described “artist and stutterer from Virginia,” began his performance by posing in stillness, bent forward at the waist, his saxophone across his back; projected on a screen was an excerpt from “Beloved” followed by a series of close-up photos of named botanicals: American chestnut (castanea dentata) and the mountain laurel (kalmia latifolia), among others. He slowly rose and began to play an improvised soundscape, mixing his own deep exhales with the melody.

Sarah Jane Cervenak, professor of women's, gender, and sexuality studies and of African American and African diaspora studies at the University of North Carolina-Greensboro, asked the artists, “How does Toni Morrison influence your artistic practice?”

“I view the archives as a place of deep creativity,” Gary responded. “I look at my work kind of like a digital quilt. This is not an adaptation of ‘The Bluest Eye.’ I wanted to conceptualize the gaze as social media and internet culture. … I view Morrison as my north star.”

“One of the many things she teaches me is about making places and spaces with the materials at hand for the artist, whether it’s words or sounds or color,” Ellis said. “I think so much about the ‘emerald closet’ [an enclosure of boxwood trees] in ‘Beloved’ and the clearing, and what Morrison said — that there is no place for us to go to remember so she had to write books as places to go. Each feels like an emerald closet, where you go and spend as much time as you need to, and you emerge, bathed.”

Amon Pierson, a graduate student in Princeton’s Department of English, said he was particularly inspired by Gary’s film. “It beautifully showed me a new way of looking at the world. It was gorgeous, riveting and compelling. The symposium was brilliant in the way that it integrated scholarship and performance, creating an experience that was both academic and affective. An event of this magnitude is one of a kind.”

‘Cake for everybody!’: Morrison’s archive inspires new theater work

A commissioned theater work, “The Toni Morrison Project,” brought the imaginative possibilities of the Morrison archive to the stage — conceived by Nicole Watson, associate artistic director at McCarter Theatre Center, as a pairing of visionary theater-makers, Mame Diarra (Samantha) Speis, co-artistic director of Urban Bush Women, and performance artist Daniel Alexander Jones, who was a Belknap Short-Term Visiting Fellow in Princeton’s Humanities Council in fall 2022, a week-long residency in which he engaged in projects with the Lewis Center for the Arts and Trenton Arts at Princeton. The two met for the first time in fall 2021 during their first archive visit. The new work was presented March 24 and 25 in the intimate Berlind Theatre Rehearsal Rooms.

Left: Mame Diarra (Samantha) Speis (left), co-artistic director of Urban Bush Women, and performance artist Daniel Alexander Jones in rehearsal for their commissioned theater work "The Toni Morrison Project" at McCarter Theatre Center. Right: JJJJJerome Ellis performs an original solo work at the symposium.

With a mille-feuille of monologue, movement and song — layered with live music — Speis and Jones conjured memory, family, community, loss and hope. Emphasizing the importance of gathering together, they broke the fourth wall to engage the audience in their creative process. Speis borrowed a program from one audience member to read from her artist statement: “I vividly remember the day I entered the room that held a selection of Toni Morrison’s inner thoughts, contemplations and her spirit of inquiry. I was at a loss for words. It called for no words, only a deep listening.” Later, Jones asked an audience member to join them at the kitchen table on the set, asking: “Would you share a memory of Ms. Morrison?” The woman smiled: “We share a birthday — Feb. 18!”

At the end, with the music keyed up to a party-pounding crescendo, Jones invited everyone into the performance space. Throwing his arms wide, he proclaimed his thanks to Ms. Morrison — “We are so grateful to you that we got to live our lives in the flow of your words” — and told the audience, “We know Ms. Morrison was legendary for her carrot cake, so we have cake for everybody!”

Novelist, poet, artist: Morrison and the imagination

In the conversation “Archival Imaginaries,” curated by novelist Angie Cruz and associate professor in the writing program at the University of Pittsburgh, the fiction writers Kaitlyn Greenidge, ZZ Packer and Nelly Rosario discussed how their archival research engenders storytelling, and how their work creates archives of its own.

“Artifacts combined can tell a more powerful story,” said Rosario. “That’s how I see what fiction can do — recombine the facts to go beyond data, statistics and photos.”

Greenidge said novels can also fill in spaces in the archive. “Fiction asks its reader to step into a totally different consciousness that can bring in audiences in a different way than a historian can. The archives are a space where there are hints of stories; the parts that are left out are usually the parts that are the most interesting.”

Ella Harris, a Princeton sophomore who is taking “African American Literature: Harlem Renaissance to Present” with Nishikawa and “Topics in African American Literature: Reading Toni Morrison” with Womack, said, “I was inspired by how the panelists encouraged us to interpret what is left out of the archive as an opportunity for re-imagining the past and what remains unknown.” One of her favorite parts of Womack’s class is the opportunity to explore Morrison’s drafts, outlines and unpublished works in the archive. “Seeing her handwriting and examining pieces of paper she wrote on never fails to give me chills,” Harris said.

In the closing plenary conversation, artist Saar and poet Shockley recalled their first encounters with Morrison’s work.

Shockley, whose newest collection of poetry, “Suddenly We,” was published last month and features Saar’s sculpture “Bluebird” on the cover, read her first Morrison novel, “Sula,” in an American literature course her first year in college, captivated by the line: “And like an artist with no art form, she became dangerous.”

Saar picked up “The Bluest Eye” at age 18. “[Morrison] gave me the opportunity to talk about the things many Black women writers felt were difficult to talk about.”

They discussed works, like Morrison’s, created in response to violence against Black people. Saar’s “High Cotton” — a grouping of five girls, 4 to 9 years old, holding tools of enslaved labor crops and with cotton bolls tied to their heads as camouflage on their way to burn down the master’s house — was created in response to the 2016 police killing of Philando Castile, whose girlfriend’s 4-year-old daughter was in the back seat of Castile’s car. “I wanted to create a piece to give these girls their power back,” Saar said.

The symposium closed, as it began, with Morrison’s extraordinary voice.

“We’ve somehow come to an end. But things never end, Morrison teaches that,” Womack said. “I thought the best way for us to close is with a passage that Morrison will pick for us.” Opening Morrison’s novel “Love” to a random page, she began to read:

“You are always thinking about death, I told her. No, she said. Death is always thinking about me…"