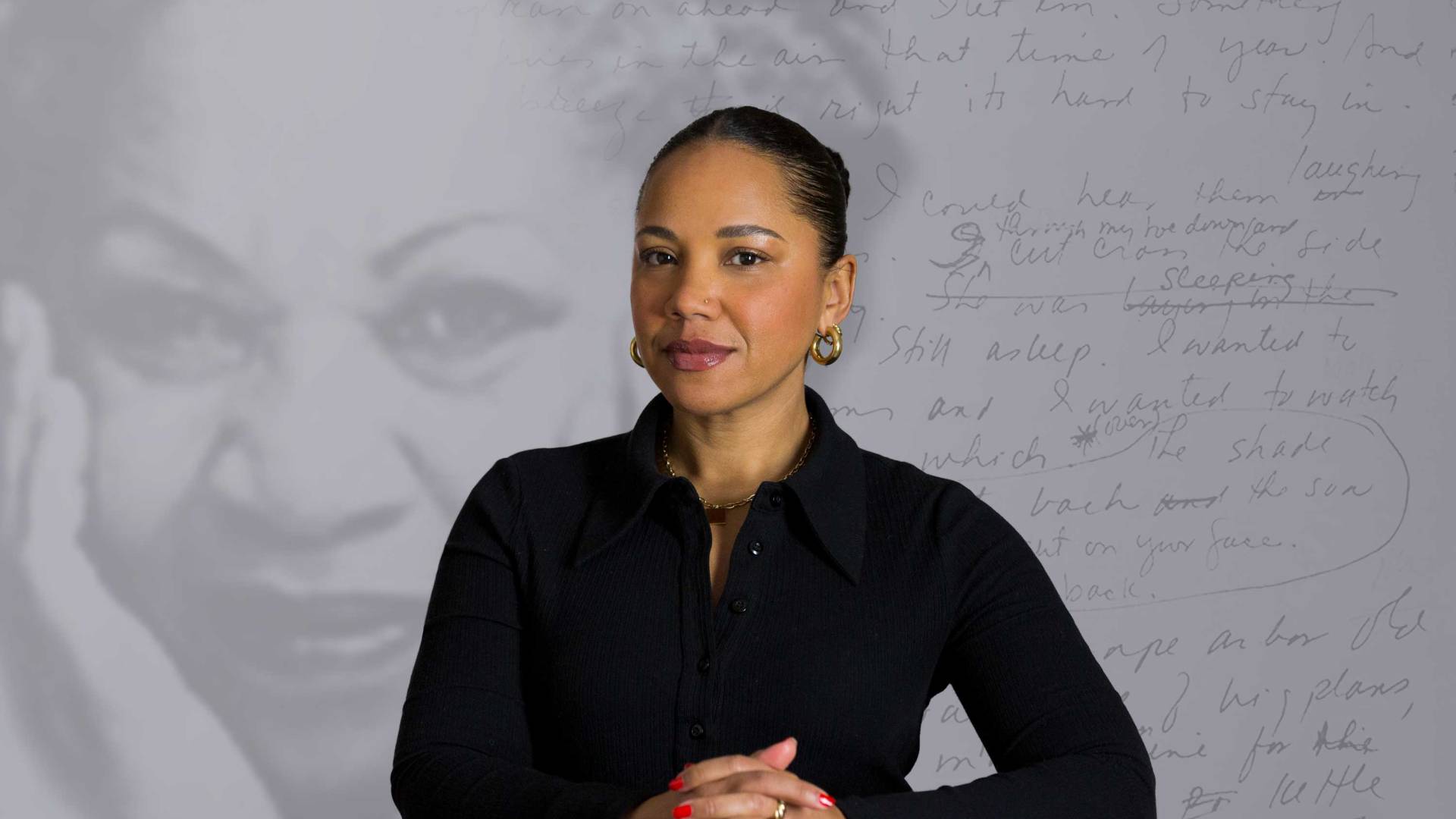

Autumn Womack, who is an assistant professor of English and African American studies, has combined her deep knowledge and teaching of Toni Morrison’s work and her passion for the archives to co-curate “Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory,” on view at Princeton University Library’s Milberg Gallery through June 4.

Autumn Womack was not a big reader growing up. But she was assigned a book for English her junior year at Central High School in Philadelphia that she couldn’t put down. She read it after school, waiting for her best friend to finish her piano lessons at Settlement Music School. She read it every night before bed. It was Toni Morrison’s “Song of Solomon.”

She had read “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” her sophomore year. “But I had never read a Black family epic — and here was Morrison, drawing upon Greek mythology to tell a young man’s journey into fantastical worlds,” said Womack, who is an assistant professor of English and African American studies at Princeton. “I could not put it down.”

On her office desk is the copy of Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” that she’s had since she was an undergraduate at George Washington University. “I still teach with it!” she said. A course she developed on Morrison’s works gives students hands-on engagement with the Toni Morrison Papers at Princeton University Library.

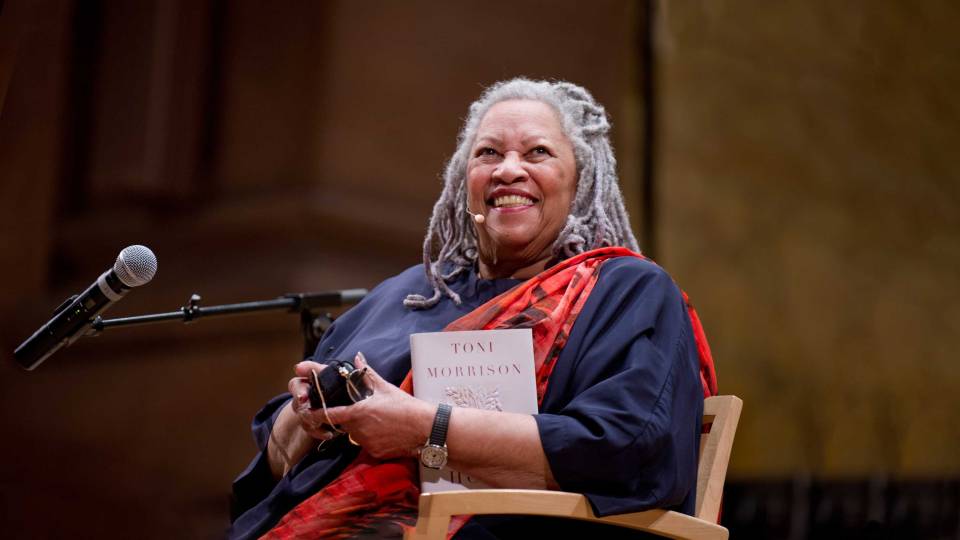

And now, at the invitation of the library, Womack has combined her deep knowledge of Morrison’s work and her passion for the archives to curate “Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory,” on view at the library’s Milberg Gallery through June 4. The critically acclaimed exhibition features early, handwritten drafts of the Nobel Prize-winning author’s great novels and sketches that Morrison drew of the places where she set the books, along with other materials from the archive that illuminate Morrison’s creative process: photographs, newspaper clippings, historical documents and more.

A love story with archives

Autumn Womack (left) and senior Isabelle Balson on a class visit to the Toni Morrison Papers in Princeton University Library's Special Collections. The course is centered on hands-on engagement with the archive.

A self-professed history nerd as a child, Womack would recreate her favorite TV show, “Little House on the Prairie,” wearing dresses and bonnets her mother sewed from calico. At a history camp in sixth grade, she was handed her first page of an archive: a census record for a person who had lived in Philadelphia — address and all. “We would see where they lived and journal in the voice we imagined that person had,” Womack said.

In college, she constantly hopped on the five-minute Metro ride to the National Archives to pore over microfilm newspapers. Her graduate school advisers were deep archival thinkers, as well, said Womack, who earned her master’s at the University of Maryland and her Ph.D. at Columbia University.

“I fell in love with this idea of stuff, this idea that there was a fuller account, another life, of an object, a person, a historical moment, a book,” she said. “I loved figuring out the stories of that other life.”

Discovering the Morrison Papers through her students

Womack said the awe is palpable when students encounter Morrison’s handwriting — and touch the pages for the first time. “This is a gift that can happen only at Princeton,” she said. Pictured: Senior Chloe Smith-Frank (left), junior Katrina Nix and sophomore Anna Borodianski in Womack's "Reading Toni Morrison" course explore some of the items in the collection.

Womack didn’t visit the Toni Morrison Papers before she first taught “Toni Morrison and the Ethics of Reading” in spring 2019. “One of the gambits of the course was to leave the discovery to the students,” she said.

In box after box, they found notes, manuscript drafts, outlines, timelines and research materials for each published book, as well as for unpublished work. There, too, were photographs, correspondence, and drafts for speeches. “She saved everything — that was a crucial part of her process,” Womack said.

Among the notes and drafts of Morrison’s 1998 novel “Paradise,” one student found a mysterious diagram Morrison had sketched on a yellow legal notepad — circles inside squares, squares inside circles, with the characters’ names, and arrows connecting them.

“We tried to crack the code, and we couldn't,” Womack said. What they did see was a part of Morrison’s creative process that wasn't about note-taking or outlining but using visualizations.

Womack came back to that item while curating the exhibition and finally broke the code. “The circle is the character’s point of view of the outside world. And the square is the point of view of the interior life of the character,” she said. “That came from what the students found and discussed.” It is on view in the exhibition section called “Thereness-ness,” a term that Morrison coined.

Creating an ‘only at Princeton’ learning experience

Womack said the awe is palpable when students encounter Morrison’s handwriting — and touch the pages for the first time. “This is a gift that can happen only at Princeton,” she said.

And students know it. Most who take her Morrison course are not English concentrators. This semester the majority are public and international affairs, psychology, and engineering concentrators. Many are seniors who know their timing is running out and told Womack they wanted to take a class that is an “only at Princeton” experience.

Womack hopes students, no matter what their concentration, will gain a new perspective from all of the difficulties that Toni Morrison’s work traverses.

“In this course, we really think about what it means to read difficult works and the lessons Toni Morrison gives us in her books for how to engage with difficult topics,” she said. “That includes difficult conversations we have with each other about violence, history, memory and racism. But it is also difficult to read her work, the sentences are beautifully challenging and in many cases they double as theories for how to read her work.”

Womack is also co-teaching a Princeton Atelier course, “Sites of Memory: Gender, Performance and the Law” with legal scholar and literary historian Patricia Williams, who worked with Morrison, writing essays for collections Morrison edited at Random House (on the Anita Hill-Clarence Thomas hearings and the O.J. Simpson trial).

Morrison, who joined the University as the Robert F. Goheen Professor in the Humanities in 1989 and taught courses in creative writing, African American studies, English and American studies for 17 years, also founded the Princeton Atelier in 1993. The academic program brings in professional artists from different disciplines, often paired with a Princeton professor, to create new work in a semester-long course.

“Patricia Williams has a deeply archival practice, and she’s an interdisciplinary thinker who works with filmmakers and artists,” Womack said.

As Morrison did, the students are "imagining out" other archival stories from flashpoints in American legal history with Black women at their center, Womack said. The focus of the course is a sustained close reading of Ketanji Brown Jackson's Supreme Court confirmation hearing. Working throughout the semester in collaboration with visiting filmmakers, visual artists and performers, the students’ final showing will be a visual or expressive original work — such as a short film, visual document or short script — that is a shared, creative record or “archive” exploring loud and quiet subtexts in the hearing.

They are taking Morrison’s “Beloved” as a starting point. Morrison began to imagine the world that became “Beloved” when she found an 1856 newspaper account of the trial of Margaret Garner, a fugitive enslaved woman who had killed one of her children and was taken back into custody. Womack said the question of the trial was, is she going to be charged for murder? Or is she going to be returned to her slave owner, a process that would confirm her status as commodity rather than a person, who could be charged with a crime?

Anatomy of the curatorial process

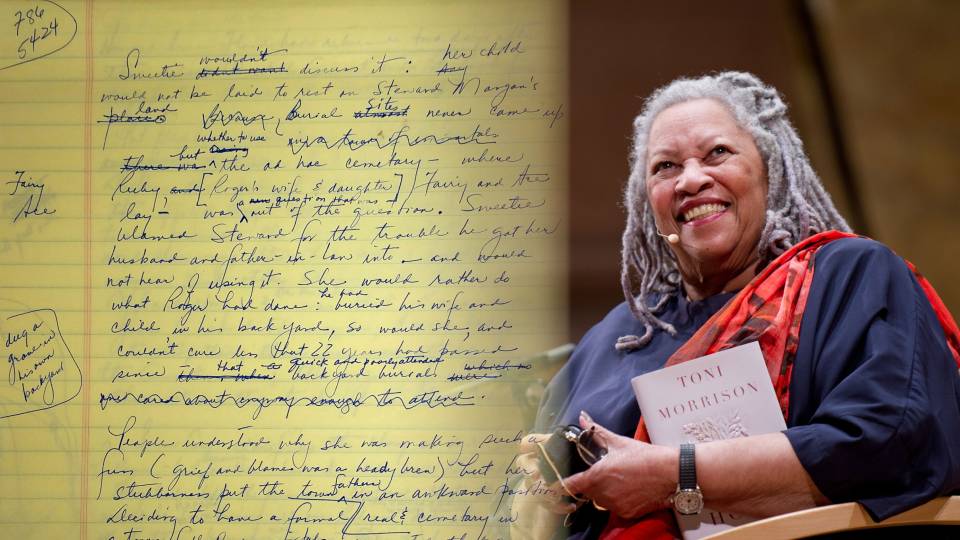

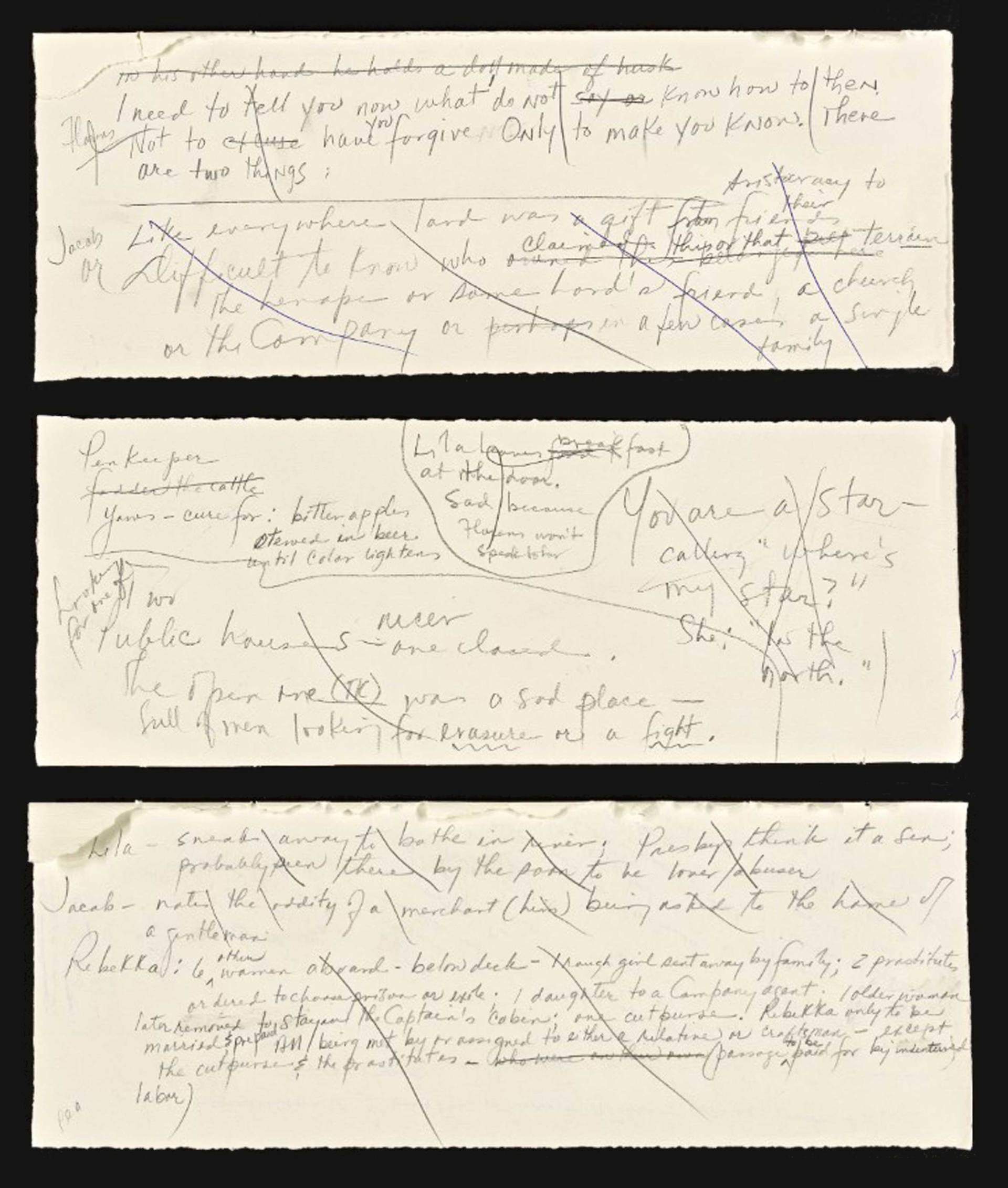

Handwritten notes from Morrison's novel "A Mercy." Toni Morrison Papers, Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

At the beginning of the summer 2020, Womack and her team for the “Sites of Memory” exhibition — René Boatman, Morrison’s long-time assistant, who now serves as a consultant to the collection, and two graduate students in the Department of English, Andrew Schlager and Kierra Duncan — found themselves face to face with the 400 boxes that make up the archive.

“They asked me, ‘What should we be looking for?’ Womack said. “I replied, ‘Nothing. Let the archive tell you what the story is.’ I didn't have a vision. This is also how I research.”

That story, Womack said, is usually not the story you think you want to tell.

What eventually emerged that summer was a story about Morrison’s creative process. “We began to see connections across each corner of the archive,” Womack said.

They discovered early on that Morrison was deeply invested in geography and mapping — whether drafting an essay, a speech or a novel.

In the files for “Beloved,” for example, they found research material about plantations in Kentucky and maps of the Ohio River, as well as hand-drawn maps that Morrison sketched of the house at the center of the novel: 124 Bluestone Road, at the edge of Cincinnati. One of these is on view in the exhibition.

Another thread the team discovered was the alternate “lives” of Morrison’s texts — a different ending, a different point of view.

In the exhibition section called “Speculative Futures,” the family tree Morrison created for “Beloved” reveals that she originally imagined the book as three volumes, in which the character of Beloved haunts each generation, Womack said. Also on view is the first iteration of Morrison’s novel “Tar Baby”: a screenplay.

Morrison wrote whenever the idea struck. A 1993 fire at her house in upstate New York destroyed much of her papers; all of the notes for “Song of Solomon” were thought to be gone. But the curatorial team discovered the outlines and drafts for that novel written around appointments in her day planners from her time as an editor at Random House. Some of the fire-singed remains and day planner pages appear in the exhibition section called “Writing Time.”

Inviting the public inside the mind of a writer

As she envisioned the exhibition, Womack created different access points for the general public — from an excerpt of a 1987 video interview with Morrison to a small exhibition across the hall at Cotsen Children’s Library of the children's books Morrison wrote.

“We go to science museums to learn, how does the heart work, how does the light bulb work?” Womack said. “Here, you can see, how does the mind of a writer work? I've tried to lift up the hood. It’s an invitation for people to engage with Toni.”

Looking under the hood also taught her an unexpected lesson.

“The amount of revisions Toni Morrison would go through — it takes a certain kind of patience,” she said. “I imagine she got frustrated but worked it through until it felt right. There were many times during the curatorial process — nearly three years — that were exhausting. But I learned to cultivate that kind of patience too.”

Developing new work inspired by the archive

In addition to curating “Site of Memory,” Womack orchestrated a robust slate of related programming. “It was intuitive,” she said. “The archive felt so alive and so multidisciplinary that just displaying the objects themselves didn't feel like the end of the story.”

Womack orchestrated a robust slate of related programming, including a landmark symposium (March 23-25) and performances of commissioned new works by (from top) Daniel Alexander Jones (McCarter Theatre Center, March 24 and 25), Cecile McLorin Salvant (Princeton University Concerts, April 12) and Mame Diarra Samantha Speis (McCarter Theatre, March 24 and 25). An exhibition by contemporary multimedia artist Alison Saar is on view at Princeton University Art Museum's Art@Bainbridge now through July 9.

Again, she let the archive speak. Morrison had curated an exhibition at The Louvre, and she had written plays.

Womack invited several key people to visit the collection — pulling Morrison’s correspondence with artists and art-centered items such as photograph from James Van Der Zee’s book “Harlem Book of the Dead” that inspired her novel “Jazz.” “This activated the idea that the archive is a place that produces new work,” Womack said. “For Toni, the archive wasn't a dusty old place. It was a site of thinking and innovation.”

Nicole Watson, associate artistic director of McCarter Theatre, had the idea to bring two unlikely artists into the collection and see what happens. Mame Diarra Samantha Speis, the founder of Urban Bush Women, and performer/composer Daniel Alexander Jones will present “The Toni Morrison Project,” a joint performance, on March 24 and 25.

In addition, Watson and Marna Seltzer, director of Princeton University Concerts, jointly commissioned Grammy Award-winning jazz vocalist and composer Cecile McLorin Salvant to create a new work inspired by the archives. The program will be presented April 12.

Womack also approached Juliana Ochs Dweck, chief curator of Princeton University Art Museum, whose team had helped select items for her 2018 course “Blackness and Media.” Dweck introduced her to Mitra Abbaspour, the Haskell Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, who was inspired to mount an exhibition of works by contemporary artist Alison Saar, most from the museum’s collection. “Mitra saw Saar and Morrison as organically in conversation,” Womack said. “Both think about themes like memory, history, language, music.” “Cycle of Creativity: Alison Saar and the Toni Morrison Papers” is on view at Art@Bainbridge through July 9.

At a March 23-25 symposium, Sites of Memory: A Symposium on Toni Morrison and the Archive — organized by Womack and Kinohi Nishikawa, who is an associate professor of English and African American studies — scholars, artists, writers and activists will explore how Morrison and the archive inform their practice and their work. The symposium is largely funded through a Humanities Council Magic Project grant.

That same week, the Department of African American Studies will also present its Toni Morrison Lecture Series, with Farrah Jasmine Griffith, a scholar and friend of Morrison, presenting new insights into and interpretations of her work.

The exhibition is curated by Autumn Womack, associate professor of African American studies and English, with curatorial contributions from Jennifer Garcon, librarian for Modern and Contemporary Special Collections; Rene Boatman, technical administrative assistant, Special Collections; Kierra Duncan, graduate student, Department of English; and Andrew Schlager, graduate student, Department of English.

Gallery hours: The exhibition is open to the public Monday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. and Saturday and Sunday from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m. through June 4, 2023. Click here for information about group visits and public tours.