Although the course "Reading Toni Morrison" was taught virtually this fall, students were given special digital access to the Toni Morrison papers in Princeton University Library's Special Collections to explore the Nobel Laureate and Princeton professor emerita's creative process.

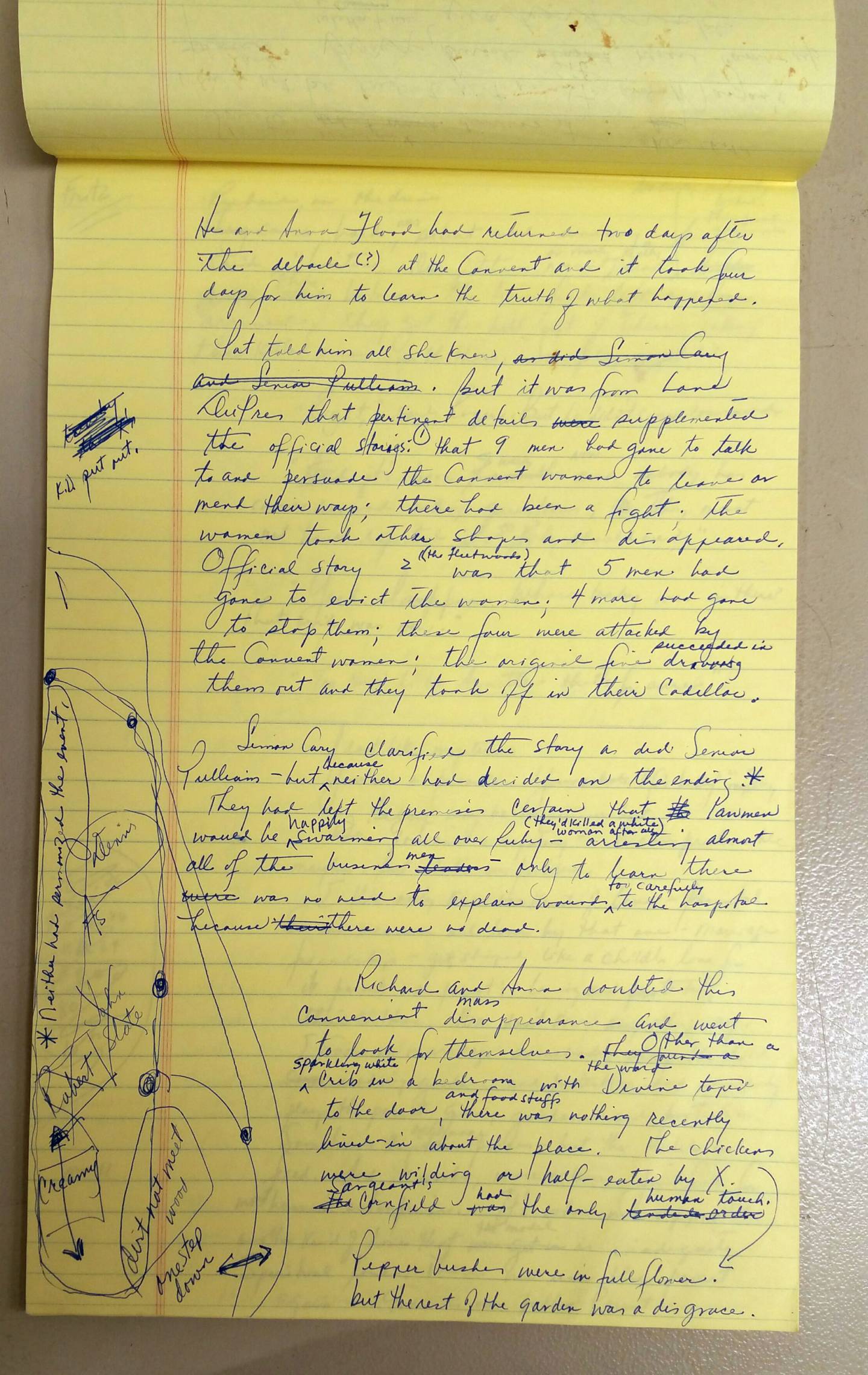

What is it like to pore over — and even touch — the handwriting of a world-renowned author on the lined notepaper on which she drafted her famous novels? What do you learn about the writing process from reading an author’s handwritten pen and pencil scribbles as she made changes to early drafts of work on typewritten pages? And what happens when access to those literary pages of gold is threatened by the pandemic?

“Studying Morrison’s literature at Princeton is really such a gift,” said Autumn Womack, assistant professor of African American studies and English. “[S]tudents are consistently amazed by the idea that they are studying her work in a place that was so important to her. More than that, we have the privilege of having access to her papers in Special Collections.”

In fall 2020, with classes continuing to be taught virtually due to COVID-19, Assistant Professor of English and African American Studies Autumn Womack faced unique hurdles as she planned her course “Topics in African American Literature: Reading Toni Morrison.” The last time Womack taught the class, in spring 2019 (then titled “Toni Morrison and the Ethics of Reading), her students regularly visited the reading room at Firestone Library to work directly with the Toni Morrison papers, which include the Nobel Laureate’s research material, manuscripts and drafts. The papers are housed in Princeton University Library (PUL)’s Special Collections.

But this time, Womack wondered: How could students obtain access to copyrighted materials online? How could they explore and investigate the archive from a distance?

In order to make the course possible, PUL’s Information Technology, Imaging and Metadata Services team, including Esmé Cowles and Kate Lynch, designed a custom authentication system for the 11 enrolled students that granted limited access to the digitized materials. The students also gained firsthand insights into the author’s creative process through an online conversation with Morrison’s long-time assistant, Rene Boatman, who now serves as a consultant to the collection and is involved in the library's acquisition of African American literature.

“When I learned that we’d be teaching online, I knew that exactly translating the power of hands-on research would be impossible,” Womack said. “But I also knew that working online could open students to a wider range of texts and create the context where they could consistently return to or reference the material.”

A draft page of "Paradise" by Toni Morrison.

She also discovered unexpected advantages. “What has been really wonderful about teaching online is that we can just stop in the middle of class and turn to a piece of material from the papers,” she said. “I can weave in an in-class exercise where students speculate about how a certain file of research material shaped the text.”

Morrison joined the University as the Robert F. Goheen Professor in the Humanities in 1989. She taught courses in creative writing, African American studies, English and American studies for 17 years until 2006. In 1993, she founded the Princeton Atelier, a unique academic program that brings together professional artists from different disciplines to create new work in the context of a semester-long course. In 2012, she ‘returned home’ to Princeton to read from her then-new novel “Home,” to a packed audience of students, faculty, staff and community members in Richardson Auditorium. She died in 2019 at the age of 88.

Womack’s students said the experience of working with the digital archives was meaningful in several ways.

“We were really lucky, as some of the only people with access,” said Isabel Griffith-Gorgati, a member of the Class of 2021 who is concentrating in English and has taken previous courses where she has enjoyed hands-on experiences with the Special Collections.

When the class read “Beloved,” one group of students gave a presentation on Morrison’s sketch of a family tree, which is part of the Morrison papers. The students emphasized how the tree raised new questions about futurity, genealogy and inheritance in the book.

Sophie Garcia, a member of the Class of 2021 and an English major, said she admired Morrison’s commitment to research and to revision in her writing process. “We found instances in the archives where Morrison did a lot of name changing to make something more meaningful. We all know there is intentionality with authors, but it’s so impressive with Morrison.”

Archives and conversations: Studying Morrison at Princeton is ‘a gift’

Following a fire in her home in 1993, Toni Morrison began donating her notes, manuscripts and related materials to Princeton University Library. Pictured: A corrected page draft from "Tar Baby."

Boatman joined a class session through Zoom to share her experiences working with the renowned author for over 20 years, who she describes as a prodigious reader and thorough researcher.

Boatman said: “For example, some of the many logistical questions that had to be answered during the writing of ‘Home’ were: What were the conditions in Korea? Due to redlining, where could Black folks live in 1950s Portland? By what means is a Black man able to travel from Portland, Oregon, to Lotus, Georgia, where could he eat, stay the night? When were public services such as water and sewer available to rural Georgians?”

Morrison loved the research involved in a project and admitted that it was sometimes difficult to know when to stop, Boatman told the students. “When you read her books, you realize how seamlessly she wove her discoveries into the creative fabric of her work,” she said.

When asked what she admired most about Morrison, Boatman said: “Ms. Morrison knew what she wanted. Nothing got in the way of her work. She was not distracted by things she didn’t want to be distracted by. I admired that focus.”

Griffith-Gorgati said she appreciated learning about the trajectory of Morrison’s career and her impact not only as a writer, but also as an editor at Random House.

Garcia said: “This has been the highlight of my semester. It was the class I looked forward to each week. It was the closest to what it could have been in person, a credit to Professor Womack.”

“Studying Morrison’s literature at Princeton is really such a gift,” said Womack. “Because she taught at Princeton for so many years and was so deeply connected to the campus and community, there is a special feeling of proximity to the work and students are consistently amazed by the idea that they are studying her work in a place that was so important to her. More than that, we have the privilege of having access to her papers in Special Collections.”

To learn more about Morrison, read the University’s story on her life and legacy and the Humanities Council’s Memorial Resolution.

Editor’s note: This story is part of PUL’s Teaching with Collections series.