Students in the fall 2020 course “Language to Be Looked At” examined modernist and avant-garde experiments in word and image, including engaging with Princeton University Library (PUL)'s Special Collections. For the final assignment, students were asked to identify gaps in PUL's "concrete poetry" collections — particularly works by women, gender nonconforming, Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and Asian artists — and make acquisition recommendations. After the course ended, PUL acquired all the recommendations that were available for purchase in support of its goal to expand collections to reflect historically underrepresented groups.

Tearing and flinging vibrant shreds of paper into the air, 13 students in 13 different locations across the United States and Canada orchestrated a visual and physical act that connected one another virtually through a grid of Zoom screens.

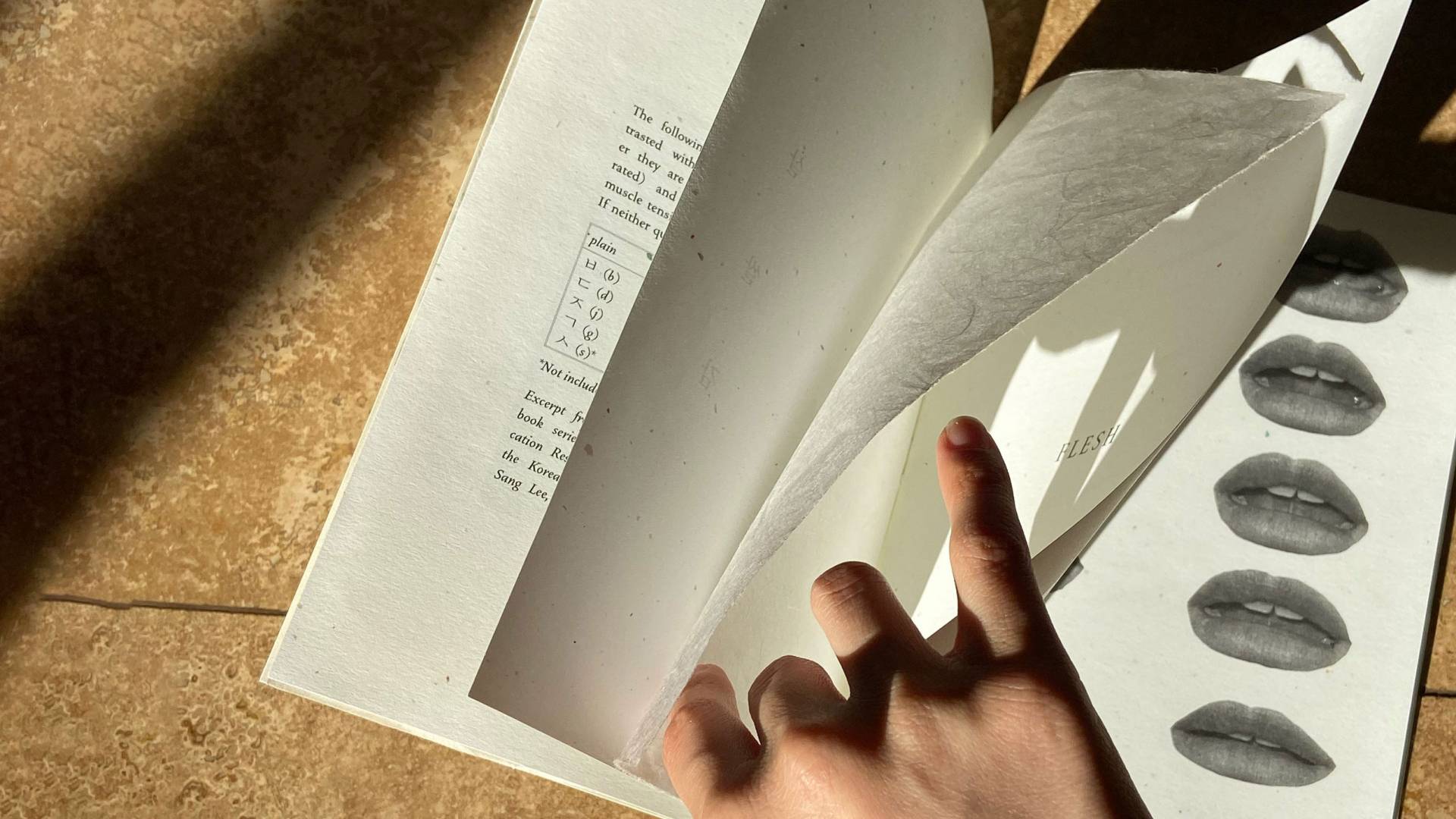

Students created their own pieces of concrete poetry during the course. For example (second piece from top), Cameron Lee, a member of the Class of 2022, included images of her mouth pronouncing Korean words as an expression of her feeling of disconnection that exists through language.

This cathartic release was an exercise in performative poetry, a realization of Benjamin Patterson’s “Paper Piece” (1960), which presents performers with instructions to enact and bring the score to life by crumpling, twisting and throwing paper into the air.

In fall 2020, students examined modernist and avant-garde experiments in word and image in the 20th century in the course, “Language to Be Looked At,” co-taught by Joshua Kotin, associate professor of English, and Irene Small, associate professor of art and archaeology. The course was crosslisted in the Program in Humanistic Studies, English, and art and archaeology.

Following World War II, artists from around the world extended experiments with visual poetry, text-based art, and what came to be known as “concrete poetry,” all of which explored the materiality of language in different ways.

“Poetry is not something that lives solely on the page, but it also has an interesting structural relationship to that page,” Small said.

Though Kotin and Small originally planned the course to be taught in-person, the pivot to virtual teaching linked students together via Zoom, not unlike the way in which the global community of concrete poets collaborated and communicated from all corners of the globe in the 1960s.

“These artists were incredibly distant from one another — in Brazil, England, Japan, Czechoslovakia, Canada — and relied heavily on the mail,” Kotin said. “During this class, we too were connected in strange and interesting ways, and by recreating that, we ‘thematized’ it and interrogated it in a way that we wouldn’t have been able to if we were all together in person.”

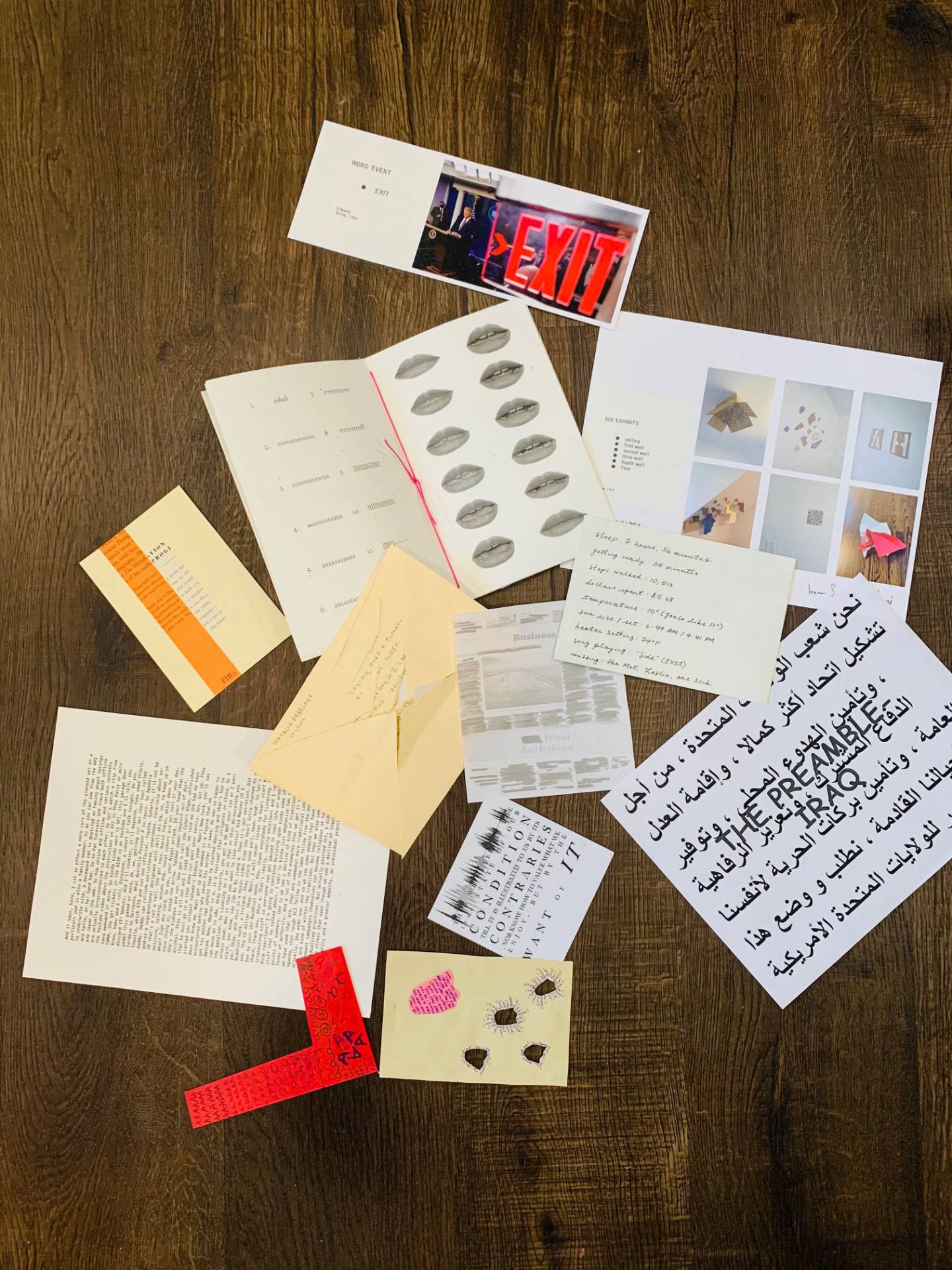

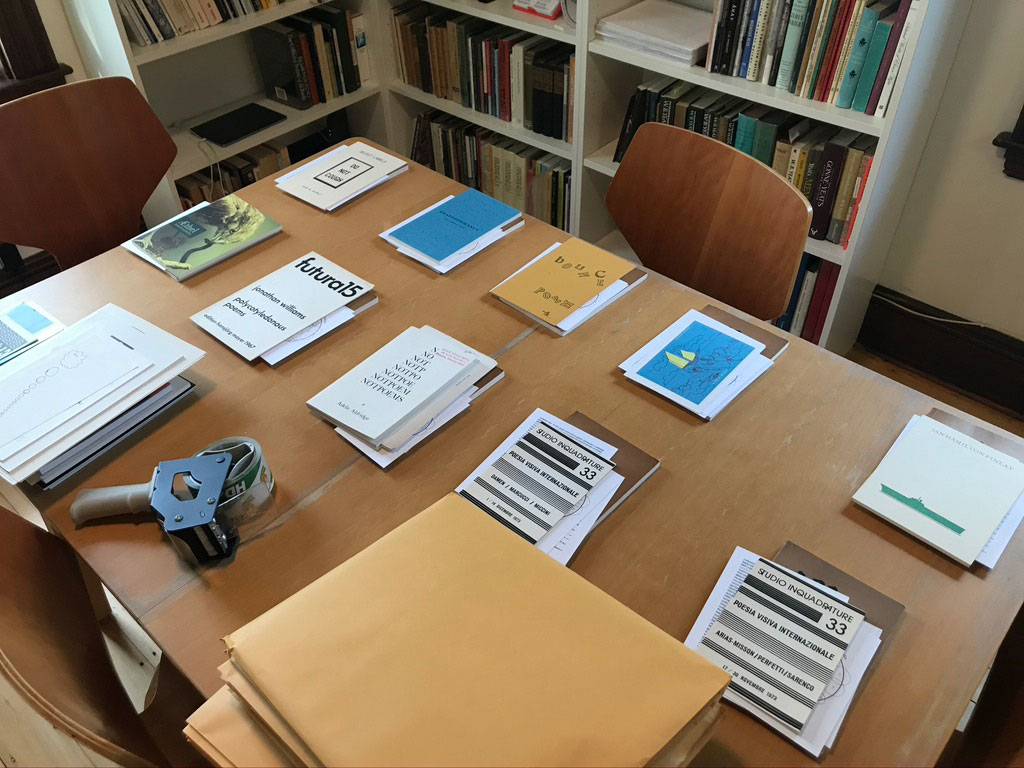

Developed through the Humanities Council Magic Project, this humanistic studies "breakthrough seminar" enabled Kotin to acquire enough concrete poetry ephemera to provide two items, such as postcards and small publications, to each student in the class. Kotin and Small assembled and mailed course packets that included these archival items, facsimiles of some historical works, as well as materials to be used by students to create their own concrete and visual poetry.

Course packets included two items of archival material, facsimiles of some historical works, as well as materials intended for students to create their own poetry and artwork.

“We wanted to give students the sense that they too can be practitioners,” Small said.

For one assignment, students mailed 13 copies of a work of their own creation to Small, who compiled the contributions and sent each student a complete “assembling,” as these gatherings are termed, of the collective work. One copy is archived in Princeton’s Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library.

Cameron Lee, a member of the Class of 2022 and an English concentrator who is also pursuing certificates in Asian American studies and East Asian studies, chose to examine her relationship with the Korean language through a book combining text and images. “My family is Korean, but I hardly know how to speak or understand the language, so I harbor a lot of guilt and shame whenever I try to speak, particularly once my grandma began living with us a few years ago,” Lee said. “My mispronunciations are a constant reminder of the distance that exists between us.”

Lee decided to explore the pronunciations of these words as a way to express her desire to reconnect with her family through language. She used images of her mouth shaping the words in speech on several different kinds of paper to emphasize the materiality of experiencing words. “The process of lifting the translucent paper to reveal the next page is almost like peeling away layers of skin, which is metaphorically representative of my attempt to shed my negative emotions through the work so that I can reach, or ‘touch,’ so to speak, my grandma,” Lee said.

Kotin and Small worked closely with Princeton University Library (PUL)’s Special Collections staff to provide creative solutions to facilitate close readings of poetry that can be fundamentally tactile or ephemeral in nature and engaging of the senses of sight, sound and touch.

Special Collections staff produced several videos of 3D objects to be used in virtual class discussions. For one class session, Sarah Hamerman, project cataloging specialist for rare books, provided a live Zoom ‘tour’ of poetry collections to emulate the experience of hands-on discovery, using a hovercam, a Zoom-compatible overhead document camera designed with distance learning in mind.

“It was important for students to have a material sense, even at a distance, of what it's like to open the collection box, move through and select items,” Small said.

Students, who are concentrating across a range of academic disciplines — theater, art and archaeology, and English — gained insights through these different lenses during class discussions.

Priyanka Aiyer, a member of the Class of 2023 and an English concentrator, said: “As someone who grew up with many different languages, language is an important medium to me. I enjoyed how the course looked at both language and art, an intersection of my great loves.”

Expanding Princeton’s collections: Students recommend new acquisitions by historically underrepresented groups

For the final course assignment, Kotin and Small asked students to identify gaps in PUL's concrete poetry collections — particularly works by women, gender nonconforming, Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and Asian artists — and make acquisition recommendations.

Aiyer recommended a book by Julian Nicolai, a multilingual Italian experimental poet, who, she said, “carved a space for herself in art and poetry.” The book, written in Italian and English, focuses on what it’s like to grow up between homes and to feel like one doesn’t have a place in one’s own country, Aiyer said, which resonates with her.

After the course ended, PUL acquired all the students’ recommendations that were available for purchase in support of its goal to expand collections to reflect historically underrepresented groups.

Learn more about PUL’s collections of concrete and visual poetry online.

This story is part of PUL’s Teaching with Collections series.