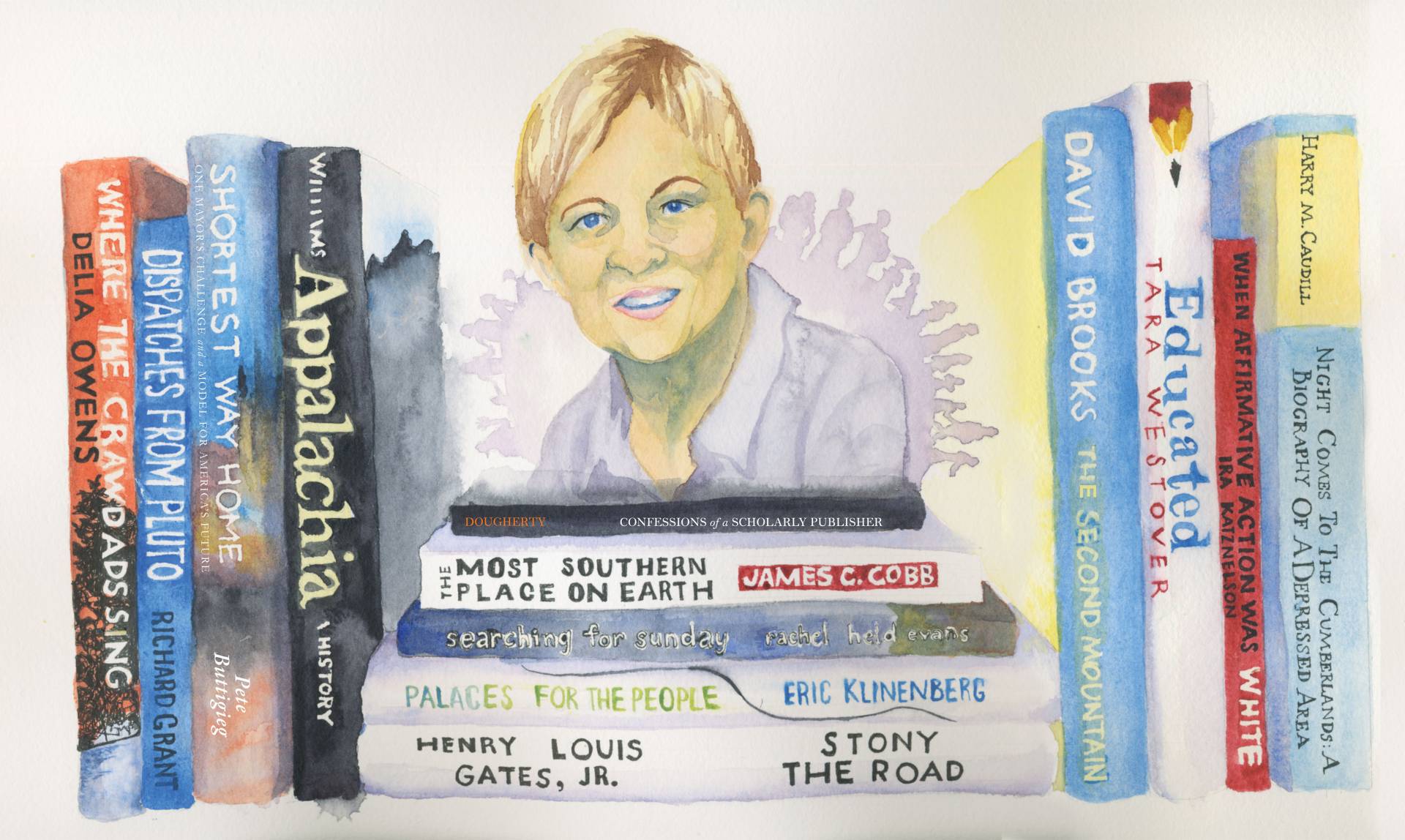

Five Princeton professors talk about how the books on their shelves relate to their work and share what’s on their summer reading lists. The illustrations, by Matilda Luk, depict a curated selection each professor pulled from their bookshelves, including one book of note.

Editor’s note: These musings were gathered during the academic year as arts and humanities writer Jamie Saxon and science writer Liz Fuller-Wright interviewed various professors for stories and projects for the University homepage and social media.

Kathryn Edin, professor of sociology and public affairs, Woodrow Wilson School

Kathryn Edin

Tell us about a particular book on this shelf.

“When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America” by Ira Katznelson turns conventional wisdom about affirmative action on its head. From the New Deal onward, a set of progressive social policies built the American middle class — for whites only. Even our seasoned policy experts seldom realize the systematic way Southern Democrats grew the gap between blacks and whites during the Great Depression and even in the face of postwar prosperity. This book should be on everyone’s bookshelf.

What’s on your summer reading list?

In June, Princeton, Stanford University and the American Institutes for Research launched the one-of-its-kind American Voices Project, which invites 5,000 households from 200 representative communities to “tell me the story of your life.” The goal of these immersive interviews is to capture in fine-grained detail the experiences of those living in poverty across our nation. This “qualitative census” of poverty will include regions that seldom have a voice in policy debates, such as the Mississippi Delta, Appalachia, the Cotton Belt, the U.S.-Mexico border and Native Nations.

Many of my “reads” are aimed at better understanding these regions. “Appalachia” [John Alexander Williams] and “Night Comes to the Cumberlands” [Harry Caudill] are histories of the Appalachian Region. “The Most Southern Place on Earth” [James Cobb] is a classic work about the Delta, while “Dispatches from Pluto” [Richard Grant] is a humorous travelogue of one writer’s year in a small Delta town. I’m particularly excited about Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s new book, “Stony the Road,” about Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow. This history still casts a long shadow over the Cotton Belt. Also, I am captivated by sociologist Eric Klinenberg’s notion that an essential ingredient in forming successful communities is “social infrastructure,” described in “Palaces for the People.”

Other reads are just for fun. Princeton University Press’s former editor, Peter Dougherty, has just published “Letters from a Scholarly Publisher,” a treat for any academic who writes books. If you haven’t read Tara Westover’s autobiography “Educated” or Delia Owens’ novel “Where the Crawdads Sing,” you are in for a treat. “The Second Mountain” by David Brooks is sure to be thought-provoking, as is “Searching for Sunday” by Rachel Held Evans, an upstart author who, according to The New York Times, “… asked whether evangelical Christianity could change. In doing so, changed it.” I had not heard of Held Evans until her untimely death this spring, at age 37, but was struck by how widely she was eulogized. And I couldn’t resist at least one political memoir — having already read Elizabeth Warren’s autobiography, I chose “The Shortest Way Home” by “Mayor Pete” [Buttigieg].

Zahid Hasan, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics

Zahid Hasan

Tell us about a particular book on this shelf.

It is a bit hard for me to pick one as I work in a truly multidisciplinary field (exotic quantum states of matter). A few books together provide the basis for my field that I consult and recommend to my students:

“Condensed Matter Physics” by Akira Isihara is read with “Basic Notions of Condensed Matter Physics” by Philip Anderson [the Joseph Henry Professor of Physics, Emeritus, at Princeton and a 1977 Nobel laureate]. Together they provide a clear introduction to some of the most significant concepts in quantum physics of matter. And much of that builds up on what we call the “language" of quantum matter, technically, “quantum field theory.” Here “The Quantum Theory of Fields” by Steven Weinberg, a 1957 Princeton graduate alumnus and 1979 Nobel laureate, is read together with “Quantum Field Theory” by Mark Srednicki.

I am lucky to have taken my quantum physics classes in the 1990s from Weinberg, at the University of Texas. That’s before he published “The Quantum Theory of Fields.” As an undergraduate, I was not sure between mathematics and physics. The coursework clearly made me pick physics over math. I am also lucky to have Philip Anderson as a colleague here in the department and a frequent lunch partner when I first arrived and began developing my research programs. As a doctoral student at Stanford, I was already familiar with his “Basic Notions of Condensed Matter,” which had a strong impact on me in choosing this topic for research.

The poet William Blake wrote, "To see a World in a Grain of Sand/And a Heaven in a Wild Flower/Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand/And Eternity in an hour" — which aptly describes my research endeavors. The books noted above form the technical bedrock of this type of scientific approach. In my lab at Princeton, we focus on exploring the bizarre quantum effects that may survive in macroscopic systems, such as in certain types of solid materials. A cubic centimeter of solid material has about as many atoms as there are stars in the observable universe. Such “condensed matter systems” are mostly described by quantum field theories. In our experiments with materials, magnets and superconductors, we find or look for analogs of exotic particles (called “Weyl fermions” or “Anderson-Higgs modes”) that may have only existed in [the] early universe. It is like seeing the secrets of the universe in a grain of sand or a speckle of dust.

What’s on your summer reading list?

It is going to be a busy summer as I will be a visiting scientist at Caltech and Stanford University’s Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) doing research. My summer readings fall into two categories — I shoot out to learn some new physics beyond my own subfield and also explore topics beyond science such as the latest in philosophy, history and religion.

On the physics side of my list is “Black Holes, Information and the String Theory Revolution: The Holographic Universe” by Leonard Susskind [and James Lindesay]. I took a class from Susskind at Stanford but never made time to read this classic. Also exciting is Freeman Dyson’s new book, “Maker of Patterns,” where he reflects on the drama of World War II, the moral dilemmas of nuclear development, the challenges of the space race — and the demands of raising six children.

Beyond physics, on my list is “Philosophers and God: At the Frontiers of Faith and Reason.” This is a collection of recent essays on thoughts by top experts edited by John Cornwell and Michael McGhee. I am hoping to get refreshed on this old debate in light of the latest discoveries and advances in knowledge. A must on my list is “The Silk Roads: A New History of the World” by Peter Frankopan — a suggestion from my wife, Sarah. I think this is guaranteed to generate some academic debates: I know she would otherwise not recommend this! Looking forward to a great summer.

Rob Nixon, the Thomas A. and Currie C. Barron Family Professor in the Humanities and the Environment and professor of English and the Princeton Environmental Institute

Rob Nixon

Tell us about a particular book on this shelf.

I adore creatively written nonfiction — that’s the writing I’m most drawn to as a reader and a teacher. Kapka Kassabova’s “Border: A Journey to the Edge of Europe” is the most compelling work of nonfiction I’ve read all year. Kassabova is a Bulgarian writer who recounts her journey by foot through the forested borderlands of Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey. “Border” is a book about layered community displacements and cultural vanishings. It is also a profoundly personal account of the power of forests — and borders — on the human imagination.

Here’s a sample of Kassabova’s spirit: “What remains sacred if a sacred mountain becomes a super-dump? I felt strongly that within my lifetime, we may all become exiles. That we may all be robbed by devouring demons disguised as policy and industry, that we may all walk down some road carrying in plastic bags our memories of forests and mountains, clean rivers and village lanes.”

What’s on your summer reading list?

My current book project — “Environmental Martyrs and the Fate of the Forests” — bears witness to the vulnerable communities battling illegal deforestation across the tropics. So, I’m planning to read or reread a succession of books that are helping us rethink the relationship between trees, especially the new science of tree-to-tree communication and cooperation. Eduardo Kohn’s “How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human,” Peter Wohlleben’s “The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate — Discoveries from a Secret World,” Colin Tudge’s “The Secret Life of Trees: How They Live and Why They Matter” are a just of few of the books I’ll be diving into.

Some of that science of botanical cooperation even surfaces in “Underland,” the new book on submerged worlds by the inimitable Robert Macfarlane, also on my summer list.

I’m always looking for exciting new books to teach. Several friends have said Nnedi Okorafor’s “Lagoon” — a futuristic novel with environmental undertones that is set in Lagos — is a classroom hit. So that’s definitely on my summer list.

Finally, I’ll also be undertaking a research trip to the Isle of Mull on Scotland’s northwest coast, so much of my summer reading will have a Scottish hue. I’m looking forward to T.M. Devine’s “The Scottish Clearances: A History of the Dispossessed,” and to the wonderful natural history writer Adam Nicolson’s “The Seabird’s Cry: The Lives and Loves of Puffins, Gannets and Other Ocean Voyagers.” Finally, I’ll relish rereading on site the world-class Scottish essayist, Kathleen Jamie (“Findings: Essays on the Natural and Unnatural World” and “Sightlines: A Conversation with the Natural World”).

Maria Gabriela Nouzeilles, the Emory L. Ford Professor of Spanish and director of the Program in Latin American Studies

Maria Gabriela Nouzeilles

Tell us about a particular book on this shelf.

“El infarto del alma” (1994, translated into English as “Soul's Infarct,” Helen Lane Editions, 2009) is a collaborative project by two extraordinary Chilean artists, the photographer Paz Errázurriz and the experimental writer Diamela Eltit. This photobook combines black and white photographs of couples — patients in love — taken in a rundown state mental hospital in Putaendo, Chile, and poetic, narrative and philosophical texts written by Eltit in response to the photographs and a visit to the asylum.

This multimedial work is the focus of a chapter in a book I am writing about the relationship between photography and other mediums including literature, painting and performance. Among other things, Eltit's and Errázurriz's book allows me to explore the relationship between image and text, and in this particular case, the role of love and the ethics of the gaze in political art that involves the encounter with vulnerable groups marked by social, racial and sexual difference. I am enthralled by the painful beauty of Errázurriz's photographs and the way in which Eltit's poetic writing both translates and opens up Errázurriz's images to new meanings.

What’s on your summer reading list?

As part of my research on the languages of photography and how it interacts with other media, I will be studying other important Latin American photobooks, such as the series on images without images by the Brazilian artist Rosangela Renno, “Universal Archive,” and “Protographies” by Colombian conceptualist artist Oscar Muñoz, which focuses on the ephemeral nature of images and the vulnerability of the archive. I will be reading and deciphering hybrid literary texts that dialogue with photographs such as “Prose of the Observatory” by the Argentine writer Julio Cortázar, the Mexican masterpiece “Farabeuf” by Salvador Elizondo, and several experimental works by Mario Bellatin. My photographic pile also includes theoretical writings on images, documentation and the real, such as “Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz” and “The Eye of History” by Georges Didi-Huberman and “The Return of the Real” by Hal Foster [the Townsend Martin, Class of 1917, Professor of Art and Archaeology at Princeton].

In addition to photography, my summer list includes readings linked to my ongoing project on modern views of nature. In this pile I placed “Do Glaciers Listen” by Julie Cruikshank and “Tierras en trance: arte y naturaleza después del paisaje,” a new book on approaches to the idea of nature in Latin American art by Jens Andermann, who has been a visiting professor in my department. Finally, I have saved some space for my literary passions and put together another pile with books by women writers and favorite poets. There I placed the exquisite book of short stories “Siete casas vacías” by Argentine writer Samanta Schweblin, “El libro de Tamar” by the Argentine poet Tamara Kamenszain and “Al que quiere!” by the American-Puerto Rican poet William Carlos Williams.

Saludos from Humahuaca in northern Argentina! (This summer I am teaching students in the Princeton in Argentina program).

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, assistant professor of African American studies

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

Tell us about a particular book on this shelf.

Historian Rhonda Williams’ book, “The Politics of Public Housing,” is so critical on multiple fronts. There has been so much ink spilled about public housing in the United States but almost none of it has looked at it from the purview of the Black women who were often the despised face of its decline. Williams’ book looks at the arc of public housing in the United States from its frame for this history. In doing so, Williams produces a more complicated view of longstanding social, economic and public policy debates that surround public housing. Williams situates these women as caretakers, thinkers, activists and policy advocates and in doing so subverts the conventional wisdom of Black women as either victims of public policies gone awry or marginal characters mostly known for the supposed domestic dysfunction that reigned in their single-parent households.

Williams then is what I would call a “people’s historian,” which is to say that she looks at history from below as a way of complicating dominant narratives that privilege the proclaimed knowledge of institutions and those that govern. In this sense, her work and this book in particular, is quite important to my scholarship. I have just completed a book, “Race for Profit: How Banks and the Real Estate Industry Undermined Black Homeownership” [forthcoming in October], where the experiences of poor Black women are central to my history of housing policies in the 1970s. Part of their experiences do include the ways that they were targeted by banks and the real estate industry to be financially exploited and the ways that public policy facilitated these efforts. Following the example of Williams, though, always means seeking to understand how poor Black women made sense of these experiences and how they responded. In my book, poor and working-class Black women make public their experiences with nefarious practices in the real estate industry and the ineptitude of public officials who failed to protect them. Their efforts to seek legal redress, while making common cause with other women experiencing the same fate, transformed private shame into public protest and, as a result, exposed the ways that Black communities had been targeted as sites of financial extraction and organized pilfering. Williams’ critical interventions as a historian helped to create the space for a book like mine.

What’s on your summer reading list?

Oh my god. My reading list is always overwhelming! I am finally getting around to reading Naomi Klein’s harrowing and dangerously lucid “This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate,” and then Michael Löwy’s “Ecosocialism: A Radical Alternative to Climate Catastrophe.” I also have Ira Katznelson’s “Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time” on the list to have some context for understanding the Green New Deal. I will also be reading Bhaskar Sunkara’s new book, “The Socialist Manifesto: The Case for Radical Politics in an Era of Extreme Inequality.”

I also plan to read David Blight’s biography “Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom” [which won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in History] and then Greg Grandin’s new book on the history of the U.S. southern border, “The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America.” I am always thinking about books that can help me provide greater understanding about the indelible impact of race in the history of the United States. To that end, I am going to read [Charles Lane’s] “The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction.” I also look forward to diving into Martha Jones’ “Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America.”

I am thinking about writing a new book that looks at the contemporary crisis of housing inequality in the United States. I am also thinking about developing a new class that looks at the relationship between race, gentrification, eviction and the ongoing struggle to secure housing. So first on the list to read is Samuel Stein’s “Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State” — super excited to dig into this book. I also want to read [Peter Moskowitz’s] “How to Kill a City: Gentrification, Inequality and the Fight for the Neighborhood.” The phenomenon of permanent housing insecurity is not just in this country, but it is a global condition. To that end, I want to read “Urban Warfare: Housing Under the Empire of Finance” by Raquel Rolnik.

Finally, I want to read further into debates concerning the direction of Black feminism. I plan to read Jennifer Nash’s “Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality” and [Princeton’s Hughes-Rogers Professor of African American Studies] Imani Perry’s “Vexy Thing: On Gender and Liberation.”