Mimi Onuoha, left, and Lauren Klein speak about data, bias and power at the Center for Digital Humanities at Princeton. The Oct. 22 event was part of the Year of Data, a campus-wide initiative to encourage critical thinking around how data shape our lives.

The Center for Digital Humanities (CDH) continued its Year of Data — a campus-wide initiative to encourage critical thinking around how data shape our lives — with a lively discussion at “Who Counts? A Symposium on Intersectional Data” on Oct. 22.

Lauren Klein, associate professor in the School of Literature, Media and Communication and director of the Digital Humanities Lab at Georgia Tech, and Mimi Onuoha, an artist, researcher and 2011 Princeton alumna, highlighted how data is dependent upon existing power structures. They challenged the audience to imagine how educators and scholars might minimize inequalities in data collection, analysis and visualization. Klein and Onuoha said that since data informs policy decisions, working to combat data bias has immediate real-world implications.

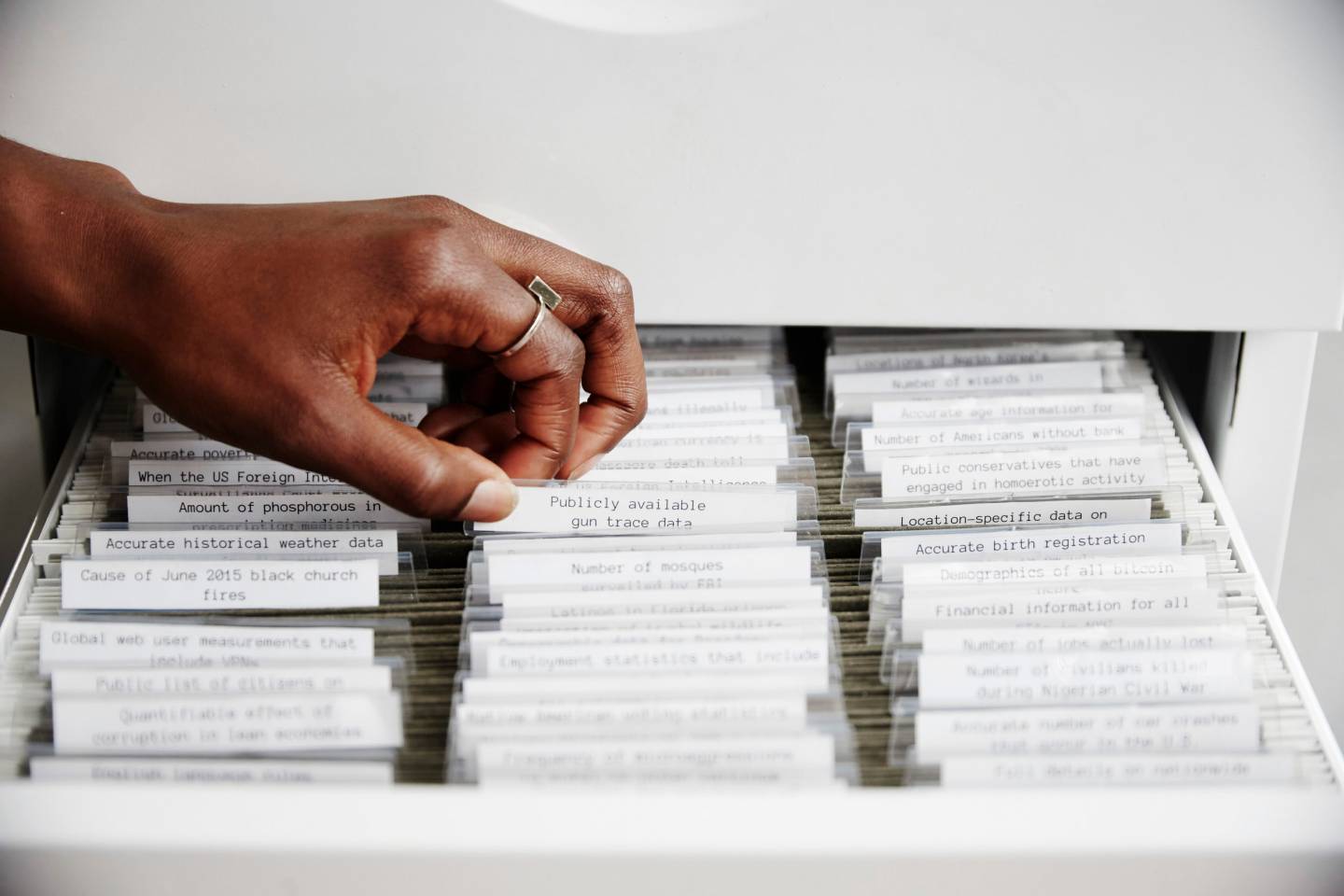

Onuaha describes her 2016 work "The Library of Missing Datasets" as an "ongoing physical repository of things that have been excluded in a society where so much is collected."

Klein elaborated on the idea of data as the “new oil,” an untapped resource that needs to be refined, drains energy and, notably, is in the hands of a small class of data oligarchs (e.g., Microsoft, Google, Facebook). Consequently, the question of what gets counted and who gets counted is decided by corporations, governments and other powerful agents that gather and analyze data with an eye toward their own interests.

Referencing her work with Catherine D’Ignazio (Emerson College), Klein clarified that “data feminism” is not just about women or even gender, but about examining power and aspiring to empowerment: rethinking binaries, considering context, making labor visible and embracing pluralism. As an example, Klein looked at how Facebook records gender. Despite appearing to let users choose non-binary genders, Facebook still requires a primary gender to create an account — data which is in turn provided to advertisers, making the categorization of “male” and “female” a key but hidden part of its information architecture.

Klein also considered the phenomenon of “missing data” and how noticing what is ignored leads to insight into social biases, a topic that underpins Onuoha’s art and research. Notably, Onuoha’s art and activism piece, “The Library of Missing Datasets,” — a repository of excluded data — offers a physical incarnation of this concept by showcasing an empty set of tabbed folders in a filing cabinet.

In her response to Klein, Onuoha offered additional examples demonstrating this imbalance of interest and power. In our “machine-readable” world, she argued, “this question of ‘Who Counts?’ becomes ever more important. What does it mean to be evaluated by someone else’s machines? What is reduced? What is lost? The question always comes back to data collection.” Onuoha referred to her study on Google published in Quartz, where she pointed out how despite robust collection of location-based data, certain populated and popular places show up as blanks on Google Maps, citing Brazil’s favelas and Lago’s lagoon settlements as just two examples.

Lauren Klein, back left, and Mimi Onuoha, front left, speak at "Who Counts? A Symposium on Intersectional Data."

The panel concluded with both speakers urging caution and compassion when collecting data on marginalized groups. Klein stressed that data collection can have harmful consequences and that making datasets visible can bring negative attention to vulnerable populations. Onuoha explained that some datasets are missing because “the act of collection can take more than it gives.” As in the case with sexual assault statistics, for example, the pain of coming forward outweighs the benefit of being counted. She closed by reminding the audience that "every missing dataset is benefiting someone by not existing,” but that examining who benefits, and therefore “who counts,” is a goal we as a community can contribute to in our research, our classrooms and our daily lives.

The discussion continued informally at a reception with CDH campus partners and event co-sponsors (Program in Gender and Sexuality Studies, Program in American Studies and the Humanities Council). The theme of data bias runs through several events in the CDH Year of Data including a keynote talk by Safiya Noble, author of "Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism," on Dec. 6. A draft of Klein’s latest book (co-authored with Professor D’Ignazio), "Data Feminism," will be published by MIT Press and open for comments during a limited peer review period.