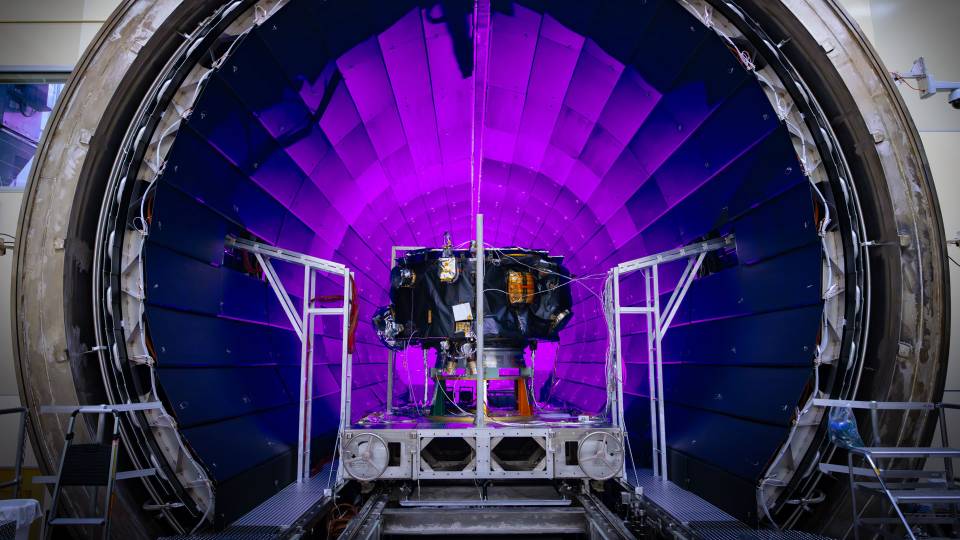

Shortly before launch, NASA engineers examined SWAPI, a Princeton-built instrument that is already collecting about a million solar wind and pickup ions each day as one of the 10 instruments aboard IMAP, the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe.

A month before arriving at its destination, the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP) has already begun to collect science data from each of its 10 instruments, NASA announced this morning.

The spacecraft, instruments and science preparation involved a team of institutions and major suppliers that spans 82 U.S. partners in 35 states, plus the United Kingdom, Poland, Switzerland, Germany and Japan, under the leadership of Princeton astrophysicist David McComas, principal investigator for the IMAP mission and a professor of astrophysical sciences.

“It’s gone even better than I dared hope,” said McComas. “Truly outstanding!”

IMAP, a one-ton spacecraft, launched from Cape Canaveral on Sept. 24, 2025, carrying 10 exquisitely sophisticated instruments to address fundamental science questions about the nature of space in our solar neighborhood.

Over the past few months, IMAP mission scientists and engineers have turned on one instrument after another, in a carefully choreographed sequence.

Princeton astrophysicist Jamie Rankin is one of IMAP’s co-investigators and is the instrument lead for SWAPI, the Solar Wind and Pickup Ion instrument, which was built in a cleanroom on Princeton’s campus.

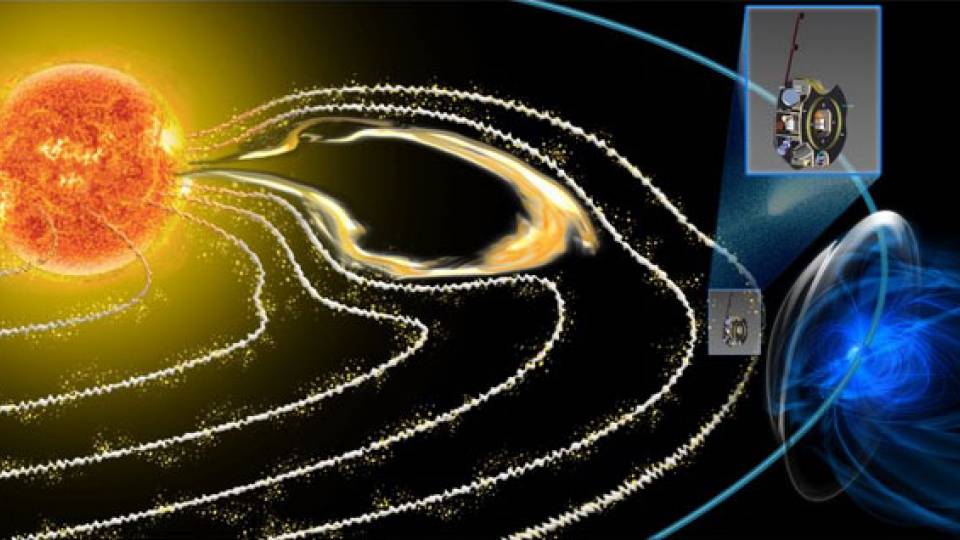

“When SWAPI turned on just over a month ago, it was in a beautiful, steady solar wind that gave us a perfectly smooth baseline to calibrate and make sure everything was functioning well. We’ve been operating in science mode ever since,” said Rankin. “It turns out that was the calm before the storm, because four days later, a powerful coronal mass ejection collided with Earth’s magnetosphere and made the aurora visible in Princeton and even down to Florida. This event was seen by IMAP ahead of time and SWAPI captured it beautifully!”

To map the heliosphere’s boundaries, IMAP includes three instruments that measure energetic neutral atoms, or ENAs, at overlapping energies: IMAP-Lo, IMAP-Hi, and IMAP-Ultra. ENAs are cosmic messengers formed at the heliosphere’s edge that allow scientists to study the complex boundary region remotely.

“It’s just astounding that we already have such good ENA data covered collectively by the three imagers,” said McComas. “This plus excellent first light data from all seven of the other instruments makes for a 10 out of 10, A-plus start to the mission.”

IMAP’s science phase — to explore and map the heliosphere, the invisible cosmic shield surrounding our solar system, and to answer some great unknowns about how particles accelerate in the solar wind — doesn’t officially begin until Feb. 1, after IMAP has been inserted into orbit around the first Lagrange point (L1), a spot 1 million miles sunward of Earth.

Even before its science mission formally begins, IMAP has not only collected expected measurements with each of its 10 instruments, it has also already found hints of possible new scientific mysteries, McComas said. During the course of IMAP’s mission, its data will lead to new science and new understandings of our heliosphere and its interaction with the surrounding interstellar medium.

“The rest of the IMAP team and I are just ecstatic about where we are at,” said McComas. “It’s an incredible joy to be seeing our first scientific data and embarking on the discovery of new things.”

After IMAP arrives at L1, the spacecraft will enter a stable orbit where it can keep pace with the revolution of Earth, staying always between the Earth and Sun.