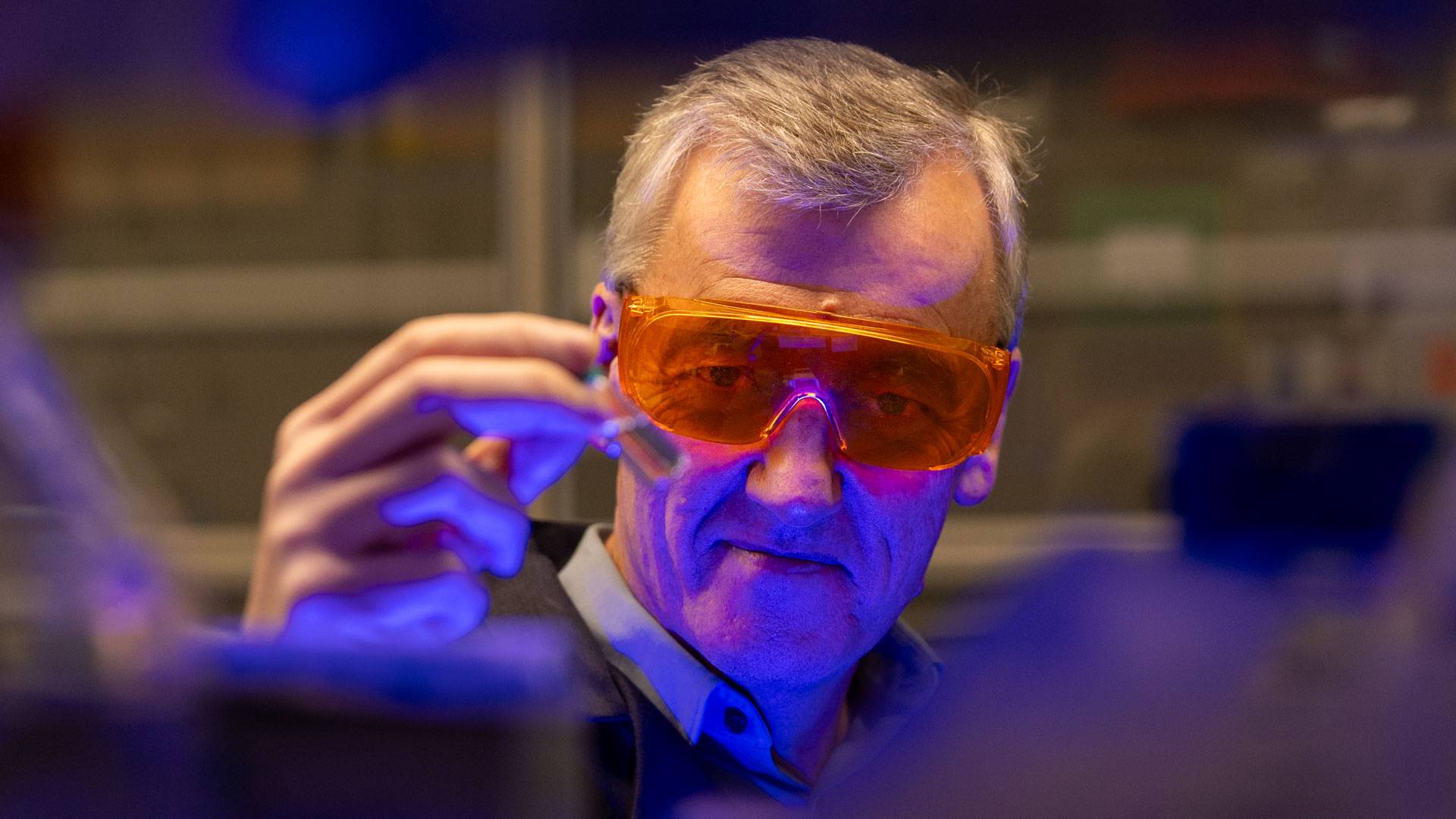

While we don’t know with any certainty which research will produce the next blockbuster result or scientific miracle, history tells us they are most likely to come from universities. Shown: Nobel Prize laureate David MacMillan, professor of chemistry at Princeton.

Princeton’s scientists, engineers and scholars tackle the world’s toughest problems and have shown again and again that they can deliver extraordinary breakthroughs, like those that launched the machine learning revolution, established the first climate models and led to a revolutionary lung-cancer treatment.

What will be the next big scientific discovery to emerge from Princeton’s labs? No one can say for sure.

Indeed, uncertainty is by design part of the model of America’s spectacularly successful research universities. “Great advances require discipline, creativity, and a profound trust in an ecosystem of scientific inquiry that accommodates uncertainty and a level of risk that is hardly ever tolerated in industry,” said Princeton Dean for Research Peter Schiffer. “Universities are where the really huge discoveries begin.”

While we don’t know with any certainty which research will produce the next blockbuster result or scientific miracle, history tells us they are most likely to come from universities.

Here’s a sampling of promising work underway across Princeton’s campus. These projects have all benefited from federal government support, and they all thrive on Princeton’s secret sauce: The ease with which experts here work across disciplinary boundaries, bringing the best ideas from varied fields to our society’s most pressing challenges.

Dementia: Understanding brain plaques with micromap

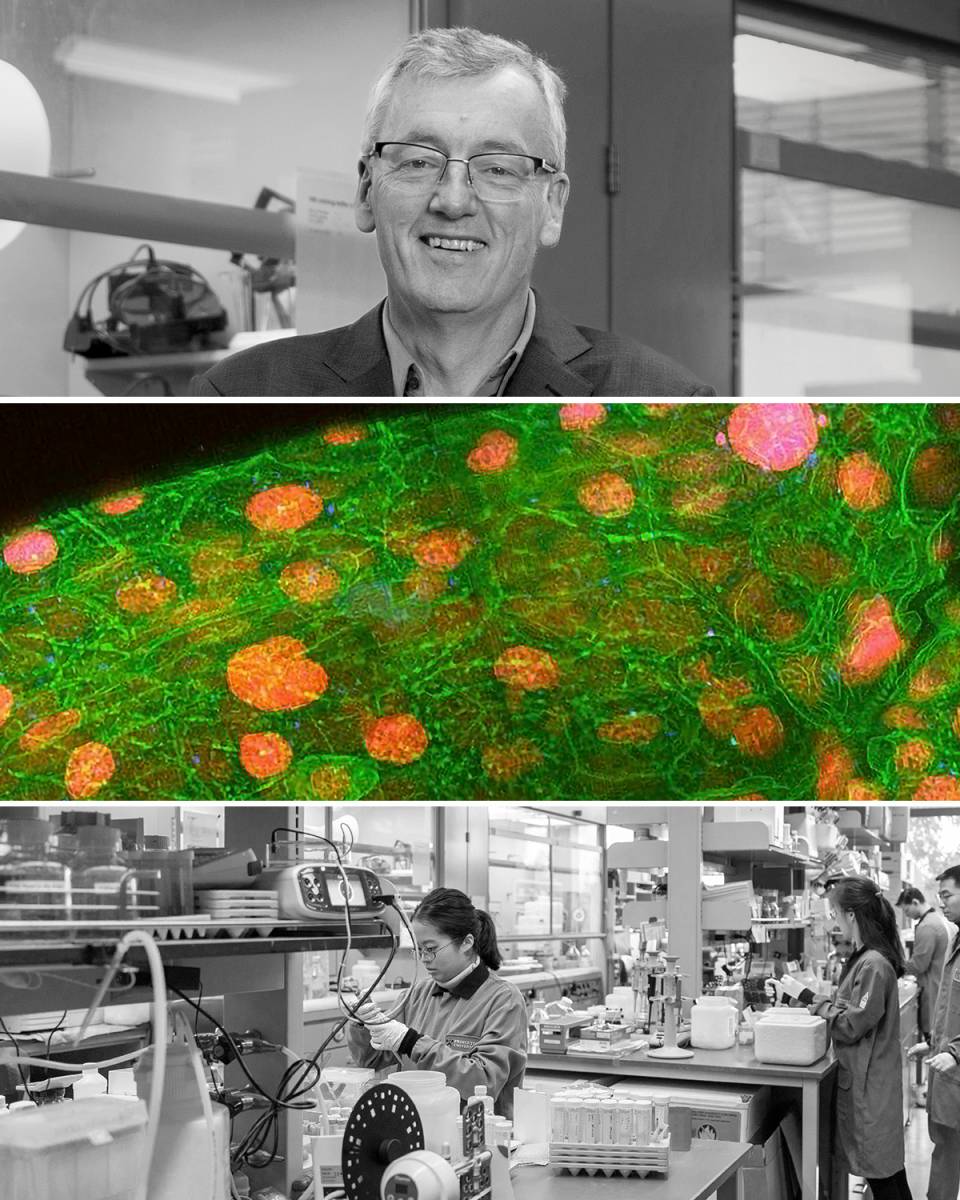

Micromap, a revolutionary tool for revealing cellular interactions, was created by Princeton Nobel laureate in chemistry David MacMillan and his team. It works like short-range microscopic spray paint, tagging cells found within a few microns of a key protein.

Recently, his team has begun flicking it on and off like a strobe light or flashlight, to track the microscopic changes that occur over time. Using prior findings from Alzheimer’s and ALS research, MacMillan’s research team used micromap to investigate how condensates form plaques in the brain — and how some break apart while others become chronic and cause Alzheimer’s, ALS and other debilitating diseases.

Armed with these new insights, they hope to identify ways to treat neurodegenerative diseases.

One of the pioneers in condensate discovery is Princeton bioengineer Cliff Brangwynne, a world leader in soft matter (blobular) cell structures.

“Cliff figured out that a bunch of proteins and DNA and stuff all come together and wrap up in a sort of bottle called a condensate,” said MacMillan. “It takes about 20 to 30 minutes to form it, it sticks around for about two hours, and then they take another half an hour or so to disassemble.”

By tracking the assembly and disassembly of these protein condensates in healthy cells, MacMillan’s team has gained insights into how they function, including identifying which proteins are key to helping a plaque disassemble — the step that is missing in brains suffering from neurodegeneration.

“If we can get that protein to re-engage, can we switch off ALS and Alzheimer's?” he asked. “A lot of us are working on this right now. It’s really exciting!”

“Once we publish that paper,” he said, “we’re going to see lots of people in neurotoxicity science asking, How do we use this for dementia? How do we use it for Parkinson’s? How do we use micromapping for all these different things?”

Computing: Chips to make the U.S. the quantum science winner

One of the most difficult challenges of quantum computing is keeping the components that store information (called quantum bits, or qubits) in just the right state to allow for calculations. That state — known as coherence time — is extremely fragile and difficult to maintain for enough time to support a working computer.

“The real challenge, the thing that stops us from having useful quantum computers today, is that you build a qubit and the information just doesn’t last very long,” said Andrew Houck, Princeton’s dean of engineering and a co-leader of a federally funded national quantum research center based at Brookhaven National Laboratory. Losing the information time after time means that quantum computers must use an enormous degree of redundancy to correct errors.

Houck, along with quantum physicist Nathalie de Leon, materials chemist Robert Cava and their research teams, are the first people in the world to make a qubit with a coherence time longer than one millisecond. That’s long enough to reduce the overhead for the mission-critical redundancy checks by a factor of 10, a major step toward enabling real quantum computing.

“This advance brings quantum computing out of the realm of merely possible and into the realm of practical,” Houck said. “Now we can begin to make progress much more quickly. It’s very possible that by the end of the decade we will see a scientifically relevant quantum computer.”

Their new chip is immediately compatible with existing hardware used by Google, IBM and other leaders in quantum computing, highlighting the vital partnership between industry and the academy.

Autism: Better diagnosis and treatment

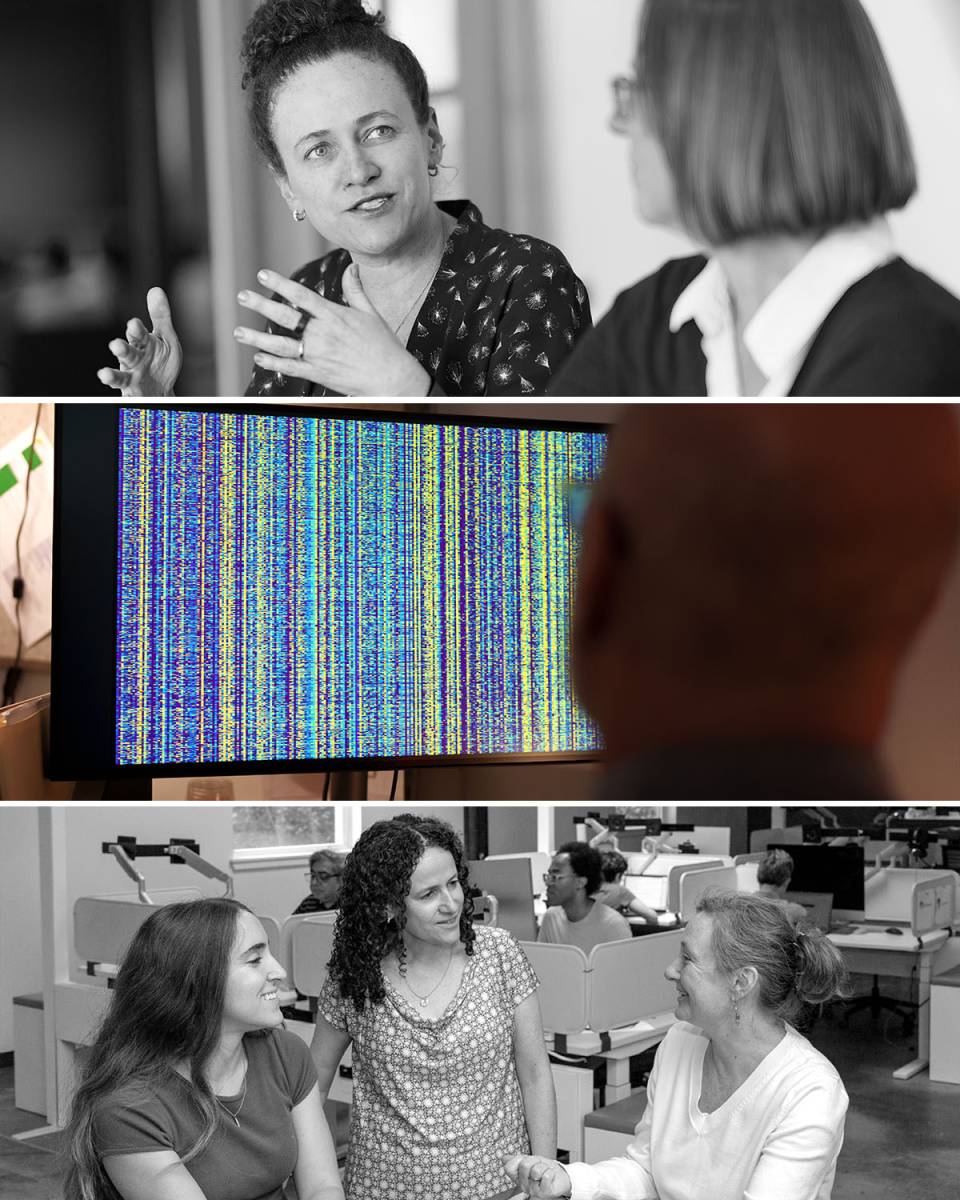

By using AI and computational modeling to analyze more than 230 traits in more than 5,000 children, Olga Troyanskaya and an interdisciplinary team of clinicians, biologists and computer scientists from the Princeton Precision Health initiative and the Simons Foundation have successfully identified four clinically and biologically distinct subtypes of autism.

The four exhibit different developmental, medical, behavioral and psychiatric traits, and importantly, key genetic and biological characteristics.

Instead of searching for a biological explanation that encompasses all individuals with autism, the team is now investigating the distinct genetic and biological processes driving each subtype. With this enhanced understanding, Princeton biomedical research could pave the way for precision diagnosis and care.

“These subtypes are very coherent,” Troyanskaya said. “Honestly, I was surprised to which extent they’re different biologically. It’s not like you have a mixture, and you're getting a little bit more of this, a little bit less of that. They are different.”

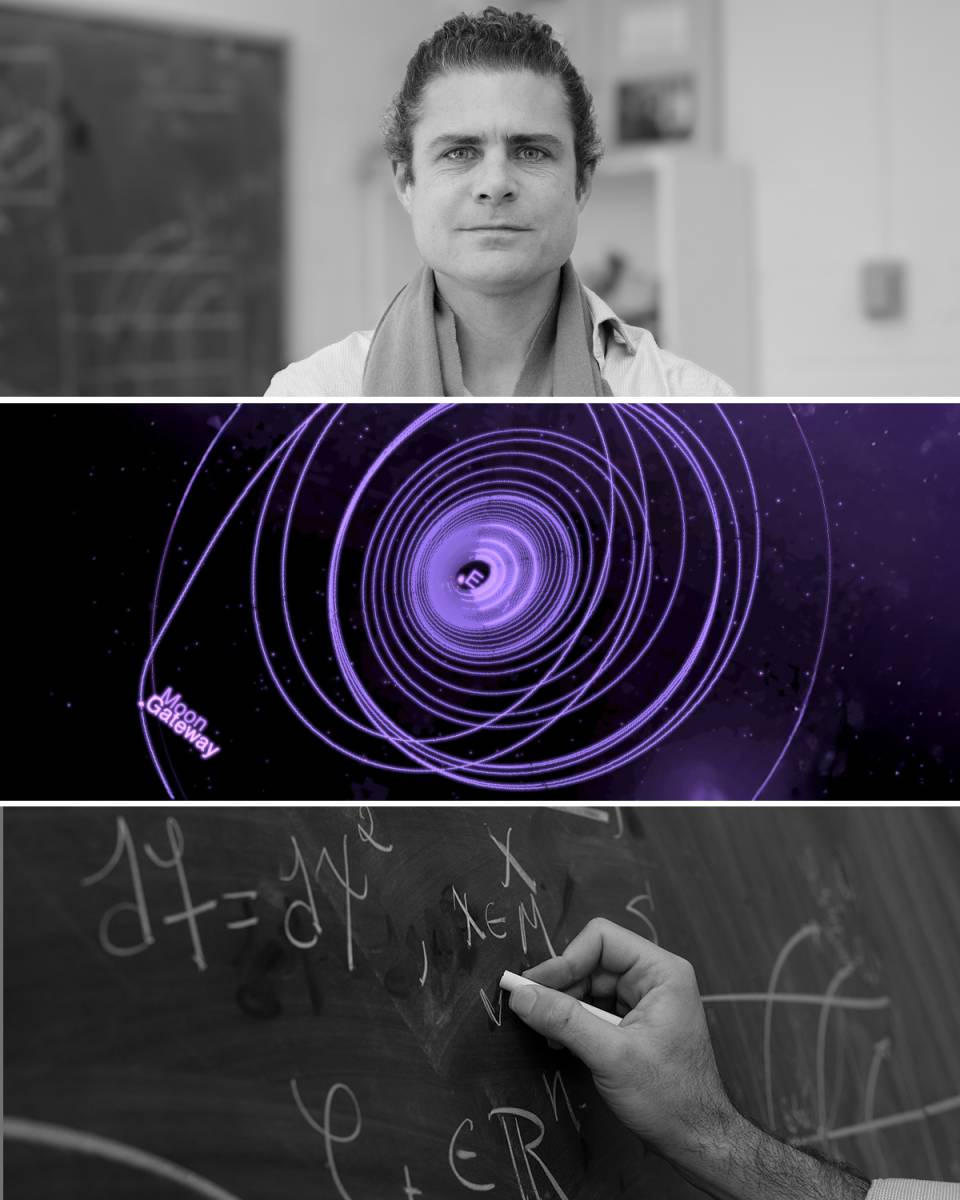

Space: Programming robots to clear up orbiting litter

Earth’s low-orbit environment in space is littered with defunct satellites, rocket parts, remnants of past missions, and many tiny particles whirling around the planet at such high speeds that they complete an entire orbit in only 90 minutes, making collisions potentially catastrophic.

As the cost of launching payloads into space has plummeted, this clutter in the near-Earth environment has proliferated at astonishing speed. In 2010, a NASA team forecast the scope of the problem well into the next century. “In their worst-case scenario, they thought that the amount of debris that we currently have in low-Earth orbit wasn’t going to occur until about 2150,” said Princeton aerospace engineer Ryne Beeson.

Beeson and his research group are working to better predict, track and forecast the movement of objects in space to reduce the risk of collisions and improve orbital debris management, especially between and around the Earth and the Moon as humanity returns there.

A deeper understanding of the chaotic Earth-Moon environment will help to sustain U.S. leadership in space exploration, advance scientific research at the Moon, enhance national security, and safeguard current and future satellites — including those crucial for modern life on Earth, such as GPS navigation, telecommunications, and Earth observations.

Beeson and Princeton colleagues are also harnessing AI to improve engineering and technology that could one day help robots be part of the space-debris solution. “By bringing together our many exceptional strengths at Princeton in materials, structures, robotics, AI and machine learning, computer vision and novel propulsion technologies, we could develop the capability to approach debris, capture it and then remediate it,” Beeson said.

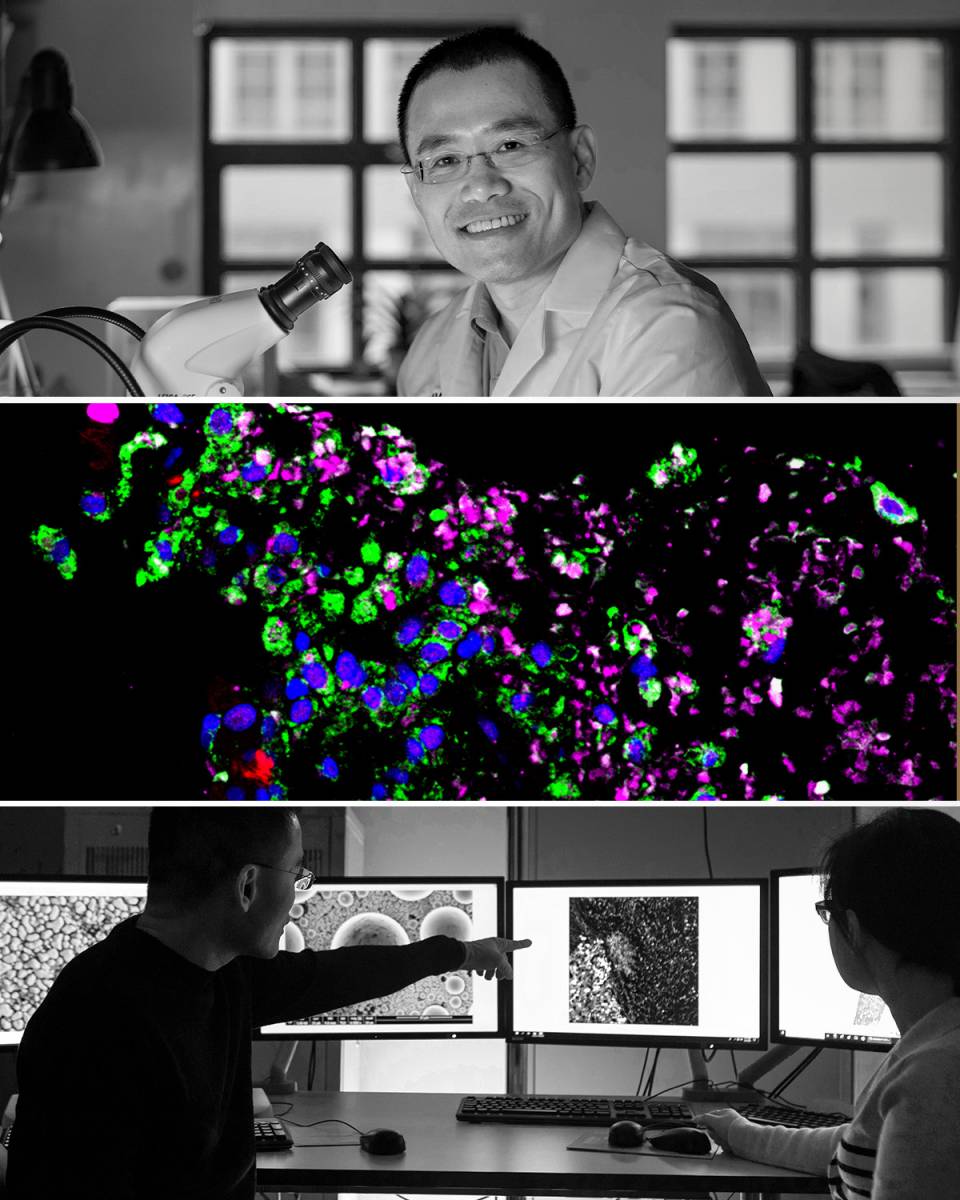

Cancer: Cellular treatments for obesity and cancer

Obesity is one of the most common preventable causes of cancer — second only to smoking. Princeton’s Yibin Kang and his colleagues have studied metastatic cancers for years.

Most people develop pre-malignant cells with cancer-related mutations during their lifetime. A majority of these cells are eliminated or controlled by normal tissue regulation and the immune system before they ever become life-threatening cancer. Kang wants to figure out how medical science can reveal those cancer-fighting mechanisms, some of which are connected to metabolism.

“What we want is to cure cancer before you ever know it’s there,” he said. “For patients that already have it, we still need to cure them, but it’s much easier to fight the battle at the beginning.”

Over the past two decades of painstaking work, Kang’s team has identified a gene — MTDH, or metadherin — that allows animals to accumulate fat for lean times but contributes to obesity and cancer.

After years of trying molecule after molecule to disable metadherin, he found a compound with the potential to thwart breast cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer, liver cancer and colon cancer. More recently, his team identified a separate pathway involving retinoic acid — a metabolic derivative of vitamin A.

Several of his team’s discoveries have begun the long journey to FDA clinical trials.

“You can almost call cancer a metabolic disease,” Kang said. “A poor metabolism weakens your immune system, promotes the proliferation of cancer cells, damages organs’ renewal ability. So I think that to cure cancer, you have to correct metabolism as well.”

Health and environment: Viral assassins for disease — and oil spills

For billions of years, viruses have attacked bacteria, and bacteria have fought back. A team of researchers led by molecular biologist Bonnie Bassler, who has pioneered discoveries of exactly how bacteria communicate with each other, has now created a host of viral assassins that can be triggered to neutralize bacteria using cues that her team has programmed in.

Many bacteria are helpful, whether in our intestinal microbiome where they digest food and fight inflammation, or in oceans where they can gobble up oil spills, or in countless other roles. Other bacteria are harmful, causing diseases like pneumonia, tuberculosis, syphilis and sepsis.

Bassler and her team are perfecting chemical kill orders to launch viral assassins against unwanted bacteria — both as medical treatments and to clear out the bacteria that have finished their oceanic scrub job.

She noted that the entire field of quorum sensing — bacterial communication — is only 30 years old. “We are only at the beginning,” Bassler said. “What is clear from our recent discoveries is that the horizon is limitless in terms of both discovery and application.”

Bassler has generated tiny populations of these assassins as proofs of concept and looks forward to handing her work off to others who will take the many practical steps between the lab bench and the broader public good.

“There is a known arc from an idea — an initial discovery — to something tangible with transformative applications,” she said. “Scientists pick their sweet spot on that path. For me, I love the very first step: making the initial discoveries. But I don't know how to make a 55-gallon drum of a medicine that is sterile and safe.

“That’s the beauty of the research partnership between universities and the government that Vannevar Bush helped expand into peacetime after it had served the country so well in World War II,” Bassler said. “And it still works — better than in any other country in the world.”

“Forever chemicals”: New hope for cleaning up PFAS

Compounds such as perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonate — collectively known as PFAS, or “forever chemicals” for their very long lifespans in soils, waterways and the human body — are widely used in products from nonstick pans to firefighting foam. They are widespread in the environment and have been increasingly associated with human health problems.

Fortunately, Princeton engineer Peter Jaffé and his research team discovered a bacterium in a New Jersey wetland that can digest PFAS chemicals. His team is pursuing two avenues to remediate PFAS-polluted areas. One is to boost this bacterium with nutrients in the areas where it naturally occurs, to encourage it to chow down on these “forever chemicals.” That approach would take several years to clean a site, he estimated.

The other approach, still in its early stages, works much more quickly. In partnership with José Avalos, who is a Princeton bioengineer and chemical engineer, Jaffé’s team has found a way to bioengineer a concentrated form of the bacterial enzyme and then apply it to contaminated soils, groundwater or water treatment systems. In test tube experiments, the enzyme destroys up to a third of PFAS chemicals within two hours.

“That’s really exciting, because it suggests we won’t have to rely on this finicky organism,” Jaffé said. “It points the way to using additional bioengineering concepts to bring this to fruition.” He estimated that, with enough funding, their enzyme could come to market in about three years.

Super foods: Wheat and rice with next-level photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is the process of turning carbon dioxide and sunlight into living green things, one of nature’s miracles performed daily by algae and plants. The process works much more efficiently in oceanic algae than it does in agricultural plants like wheat and rice. Why? Algae have evolved a remarkable turbocharger called the pyrenoid that dramatically accelerates carbon dioxide uptake.

A global team of researchers is tackling the question of how to introduce a pyrenoid into wheat, rice and soybeans to speed plant growth and thereby produce more food with fewer resources.

Princeton’s Martin Jonikas, a leader in these efforts, has spent almost two decades identifying more than 90 components of these microscopic turbochargers and learning how they work together.

Jonikas anticipates having an early proof of concept within the next year or two. As a preliminary step, his team and collaborators have successfully introduced pyrenoid-like structures into plant species that are easier to engineer than grain crops.

“I’m optimistic,” Jonikas said. “This technology, if it works, could offer substantial benefits to global agriculture. It could increase yields, decrease the amount of water and nitrogen fertilizer required, and crops will also be more resilient to higher temperatures, which we expect to face in the coming decades.”

Clean energy: Bringing fusion energy to the grid with AI

Scientists and engineers at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, a U.S. Department of Energy National Laboratory, have harnessed the power of artificial intelligence to wrangle the many complex variables involved in bringing potentially limitless fusion energy to the electrical grid.

The hardest nut to crack has been learning how to stabilize the plasma — the fourth state of matter and the fuel of fusion — at extraordinarily high temperatures and densities to produce sustained energy.

For decades, fusion scientists and engineers have attempted to test the complicated variables for magnetic containment in laboratory experiments, with endless rounds of trial and error. “We’ve had good guesses and made huge progress, but it's a phenomenally difficult problem,” said Steven Cowley, director of the laboratory and an astrophysics professor at Princeton. “It’s time to use AI to find our way through.”

PPPL scientists and engineers are now using AI to optimize among the different possible configurations. “Fusion may be the first big technology that is fully enabled by AI,” he said. He predicts that fusion energy will be delivering sustained power generation through a fusion pilot plant by the end of the 2030s.

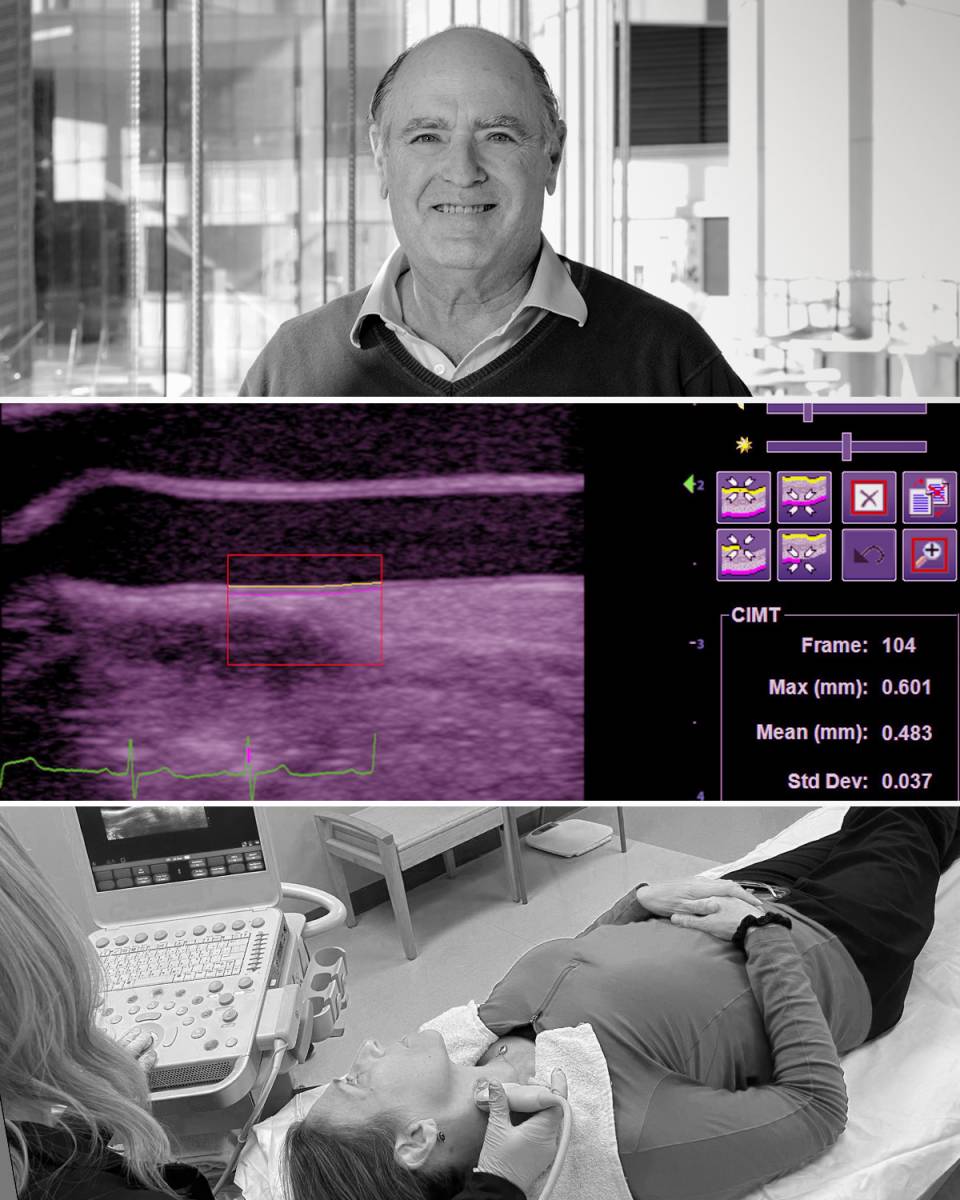

Heart health: Nipping catastrophic heart disease in the bud

Daniel Notterman, a physician-scientist and Princeton’s vice dean for biomedical and clinical research, has been a longtime partner in Princeton’s decades-long Future of Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFS), based at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs.

Fourteen years ago, Notterman observed worrisome cardiovascular risk factors in many of the 4,500 children of the study, including poverty, violence, poor diets and other aspects of adversity. His team recently measured the carotid artery wall thickness of 1,500 of the young people, now in their early 20s. The measurements suggest that without treatment, many are poised for early strokes or heart attacks.

After correlating the data with other biomarkers measured at ages 9, 15 and 23 years, Notterman and his colleagues further concluded that adversity in children and teens predicts serious heart disease in a way that can be measured even before a child is 10 years old.

His team identified “the same 50 or 60 genes being affected” over time as the young people grew. “That gives you a biomarker for evaluating the effects of early intervention and provides deep insight into the biological links between childhood adversity and later heart disease and stroke,” Notterman said.

He and his research group are searching for approaches that can interrupt the cycle and protect the heart health of at-risk young people.

Quantum sensors: Diamonds are an engineer’s best friend

At Princeton, quantum science can be roughly divided into two categories: the development of engineering breakthroughs like quantum computing that build on theoretical discoveries from the past century, and new theoretical work and measurements that will unleash the technologies of the next century.

Nathalie de Leon straddles that line. Her cutting-edge work with diamonds is creating (comparatively) stable quantum states, using nitrogen vacancies, that are already useful for precision sensors. She has also identified new properties that her diamond-based quantum sensors can detect, which could lead to developing revolutionary new materials in the decades to come.

At the new Quantum Diamond Lab at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL), machines are using plasma to create inexpensive industrial diamonds infused with other elements for de Leon and her research team to use in their experimental and theoretical work.

On the engineering side, diamond sensors open up new capabilities for measuring the world around us, including navigating efficiently by measuring the Earth’s magnetic field, detecting tiny magnetic fields that report on how electrons flow in devices and materials, and measuring the temperature of microscopic structures inside cells and helping diagnose cancer.

On the theoretical side, diamond sensors are providing a completely new way to measure materials, and “it’s hard to draw a straight line to what the ultimate technology is going to be,” de Leon said. She pointed to semiconductors, which were originally studied because people thought they would lead to better refrigerators — and instead led to computers, smartphones, pacemakers, solar panels, satellites — “our entire modern life.”

“With fundamental research, we are expanding the sum of human knowledge.”

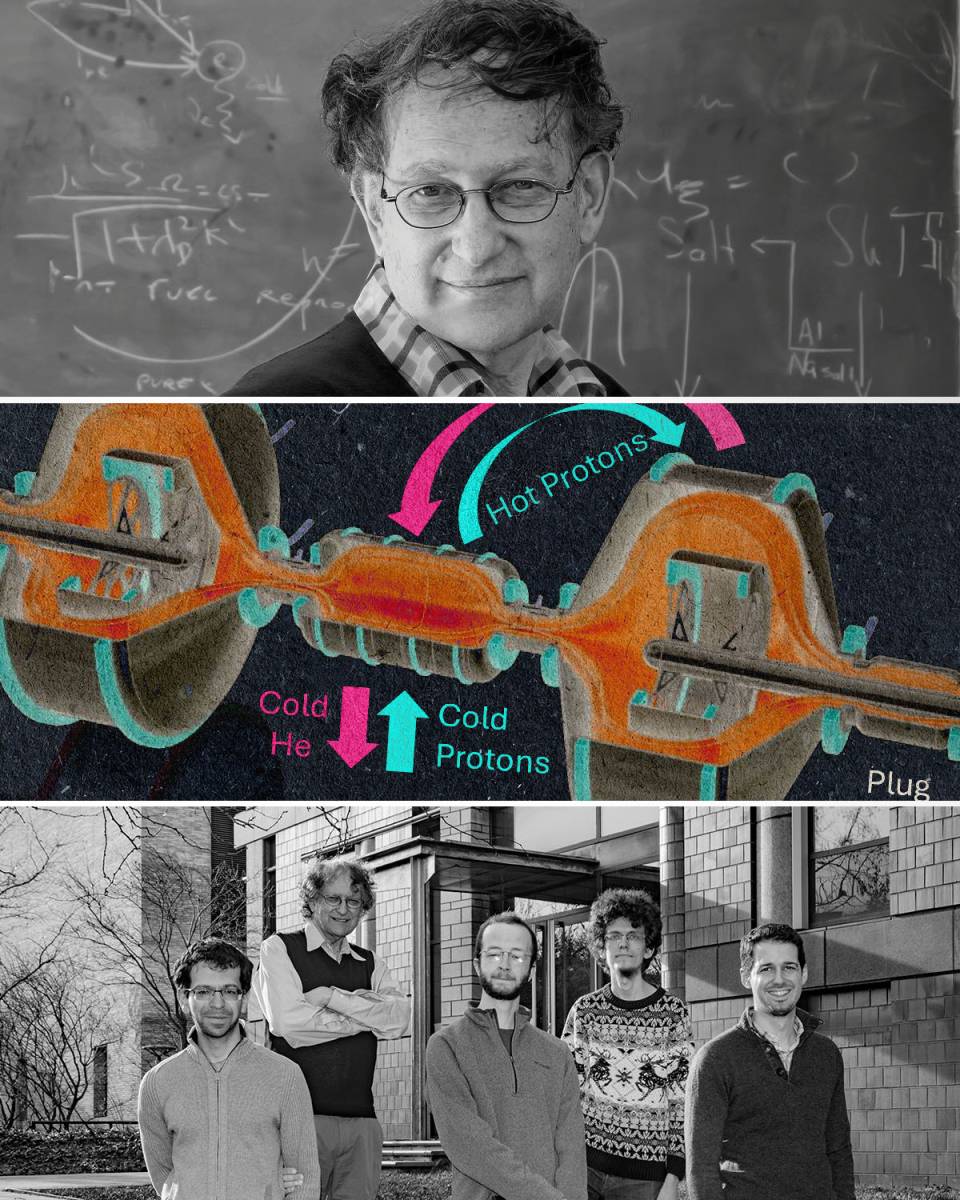

Unlimited energy: An unlikely but fantastic energy source

The proton-Boron11 (pB11) fusion reaction offers a clean, safe way to produce energy using a reaction between two naturally abundant elements: protons and boron. On the other hand, achieving pB11 fusion appears to be nearly impossible since it requires raising plasmas to extraordinarily high temperatures, among other challenges.

Physicist Nat Fisch and his team have theorized a breakthrough approach that could make this reaction possible, potentially leading to a new source of sustainable power for the world.

It requires bending the second law of thermodynamics almost to the breaking point. But if it works — an admittedly big if — it would create limitless pollution-free energy.

Fisch’s research team has shown that by cajoling the plasma with waves so as to confine the proton-boron fuel but not the helium byproducts of the reaction, and keeping protons in a hotter state than the boron, then “in a very, very narrow window, still with very high temperatures,” pB11 fusion could work.

“We’ve been working for years to disprove our concept,” Fisch said, “because if we try very hard and we fail at that, then we know that we are on the right track. Our near-term strategy is to get the science straight, and then the rest of it — the technology, the regulatory approvals, the market risk — all that is going to be so much simpler.”

.