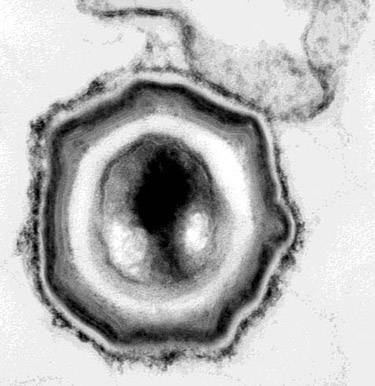

A spore from the bacterium Bacillus subtilis reveals bands, or protective coats, surrounding the spore's center. The outermost dark layer is a previously undetected extra coating of protection, which biologists have labeled the "spore crust." The discovery of this additional veneer offers insights into the resistance of bacterial spores. (Image: Courtesy of Current Biology)

Scientists have found that bacterial spores, the most resistant organisms on Earth, carry an extra coating of protection that has gone undetected until now.

The findings, reported in the latest issue of the journal Current Biology, offer additional insight into how spores of the bacteria that cause botulism, tetanus and anthrax survive methods to eradicate them.

The study was conducted by Zemer Gitai, an assistant professor of molecular biology at Princeton University; Jonathan Guberman, a Princeton graduate student who is now at the University of Toronto; and researchers at New York University's Center for Genomics and Systems Biology and Loyola University's Medical Center in Illinois.

The researchers studied the spores of a nonpathogenic bacterium, Bacillus subtilis, which is commonly found in soil. The B. subtilis spores exhibit many of the same structural features of the more lethal variety of spore-forming pathogens. In this study, the scientists examined the proteins that make up spores' protective layers. Previous research has shown that 70 different proteins make up these layers. Less understood is how these proteins interact to form the spores' protective coats.

In conducting the study, the scientists employed a host of advanced data analysis techniques, tracking the complex interactions between genes and between proteins. "This integrated approach allowed us to discover some exciting new biology, namely that B. subtilis coats have a crust layer that had been previously unappreciated despite years of study," Gitai said.

The researchers removed genes for selected coat proteins, allowing them to determine which proteins were necessary to the formation of the spores' coats. To observe proteins' behavior in living cells, the researchers fused the genes encoding the spores' coat proteins to a marker, a green fluorescent protein. This procedure allowed them to monitor how the proteins localized to form spores' protective coats.

A combination of fluorescence microscopy experiments and high-resolution image analysis enabled the researchers to pinpoint the location of the spores' coat proteins with a high degree of precision and to build a map of the spore coat. These experiments suggested the existence of a new outermost layer of the spore coat. The researchers then were able to confirm the existence of this new layer using electron microscopy.

The researchers named this coat layer, located on the spores' outer surface, the "spore crust." While it has not yet been confirmed, it is possible that the spore crust is a common feature of all spore-forming bacteria, such as the botulism, tetanus and anthrax pathogens.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.