The onset of the Great Recession and, more generally, deteriorating economic conditions lead mothers to engage in harsh parenting, such as hitting or shouting at children, a team of researchers has found. But the effect is only found in mothers who carry a gene variation that makes them more likely to react to their environment.

The study, conducted by scholars at New York University, Columbia University, Princeton University and Pennsylvania State University's College of Medicine, appears in the journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

"It's commonly thought that economic hardship within families leads to stress, which, in turn, leads to deterioration of parenting quality," said Dohoon Lee, an assistant professor of sociology at NYU and lead author of the paper. "But these findings show that an economic downturn in the larger community can adversely affect parenting — regardless of the conditions individual families face."

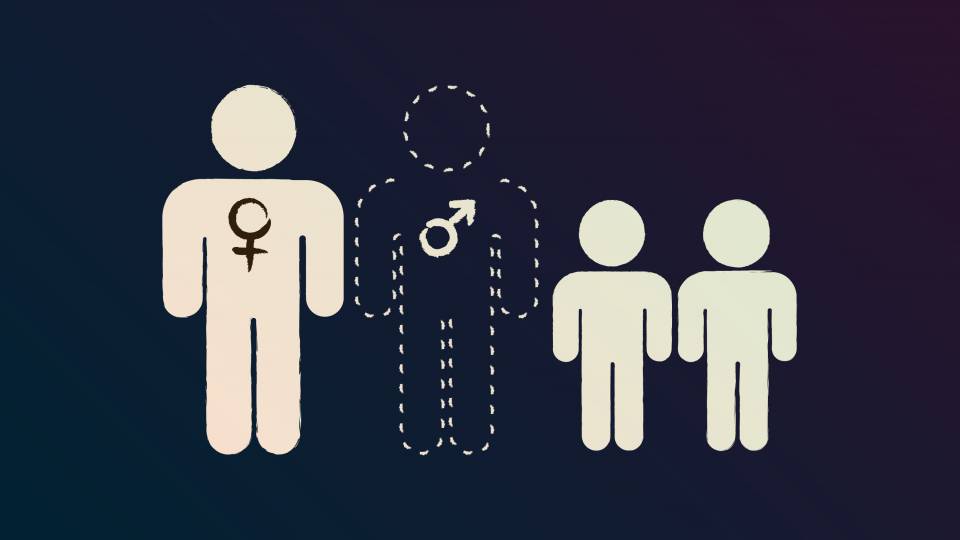

The researchers found that harsh parenting increased as economic conditions worsened only for those with what has been called the "sensitive" allele, or variation, of the DRD2 Taq1A genotype, which controls the synthesis of dopamine, a behavior-regulating chemical in the brain. Deteriorating economic conditions had no effect on the level of harsh parenting of mothers without the sensitive allele. Just more than half of the mothers in the study had the sensitive, or T, allele.

The orchid and the dandelion

Likewise, the researchers found that mothers with the sensitive allele had lower levels of harsh parenting when economic conditions were improving compared with those without the sensitive allele.

"This finding provides further evidence in favor of the orchid-dandelion hypothesis that humans with sensitive genes, like orchids, wilt or die in poor environments, but flourish in rich environments, whereas dandelions survive in poor and rich environments," said Irwin Garfinkel, a co-author of the paper and the Mitchell I. Ginsberg Professor of Contemporary Urban Problems at the Columbia University School of Social Work.

The findings were based on data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study (FFS), a population-based, birth cohort study conducted by researchers at Princeton and Columbia of nearly 5,000 children born in 20 large American cities between 1998 and 2000. Mothers were interviewed shortly after giving birth and when the child was approximately 1, 3, 5 and 9 years old. Data on harsh parenting were collected when the child was 3, 5 and 9 years old. In Year 9, saliva DNA samples were collected from 2,600 mothers and children. (Fathers were interviewed by phone for the Fragile Families study, and their DNA was not collected.)

Harsh parenting was measured using 10 items from the commonly used Conflict Tactics Scale — five items measured psychological harsh parenting (e.g., shouting, threatening, etc.) and five gauged corporal punishment (e.g., spanking, slapping).

The researchers supplemented these data with measurements of economic conditions in each of the 20 cities where the FFS mothers lived. Specifically, they examined city-level data on monthly unemployment rates, obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics' Local Area Unemployment Statistics, and the Consumer Sentiment Index, obtained from the Thomson Reuters/University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers.

In their analysis, they controlled for age, race/ethnicity, immigration status, educational attainment, poverty status, family structure, and child gender and child age (in months) at the time of interview.

The results showed that, contrary to common perceptions, harsh parenting was not positively associated with high levels of unemployment among those studied. Rather, these behaviors were linked to increases in a city's unemployment rate and declines in national consumer sentiment, or confidence, in the economy.

The researchers concluded that it is the anticipation of adversity — fear of losing one's job due to deteriorating economic conditions — that is a more important determinant of harsh parenting than poor economic conditions or even actual economic hardship a family faces. "People can adjust to difficult circumstances once they know what to expect, whereas fear or uncertainty about the future is more difficult to deal with," said Sara McLanahan, Princeton's William S. Tod Professor of Sociology and Public Affairs and a co-author of the paper.

The other co-authors of the paper are Jeanne Brooks-Gunn of Teachers College and the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University; and Daniel Notterman of the College of Medicine, Pennsylvania State University.

A focus on genes

The researchers also sought to determine if the response varied by genetic make-up. With this in mind, they studied genes that are related to these behaviors. Specifically, they considered the brain's dopaminergic system, which helps regulate emotional and behavioral responses to environmental threats and rewards. Here, they focused on the DRD2 Taq1A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). SNPs are tiny changes at a single location in a person's genetic code.

Previous studies have shown that those possessing at least one T allele for this SNP are more susceptible to reactive aggression than are those with the CC alleles. Based on these findings, the researchers hypothesized that mothers' harsh parenting behavior as a response to adverse macroeconomic conditions depends upon their DRD2 Taq1A genotype.

They found that mothers with the T allele were significantly more likely to engage in harsh parenting under deteriorating local economic conditions and declines in consumer confidence. However, they did not find such changes in parenting under worsening macroeconomic conditions among mothers bearing the CC alleles.

Finally, they found that mothers with the T allele were less likely to engage in harsh parenting than mothers with the CC allele when economic conditions were improving. This finding is especially important because it highlights the fact that the effect of genes on people's behavior may depend on the quality of their environment. In the past, researchers have focused on "bad" or "risky" genes and difficult environments without giving enough attention to how people with these genes may perform in high-quality environments, McLanahan said.

The FFS is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.