The opportunity for intellectual freedom is what drew Anna Ijjas to the Princeton Center for Theoretical Science. As an associate research scholar, Ijjas studies basic questions about the universe's origin and future. "PCTS provided an environment that encouraged me to question established paradigms and pursue unexplored possibilities," said Ijjas, who is Princeton's John A. Wheeler Postdoctoral Fellow in cosmology and astroparticle physics. "Independence and creativity are real values at the center."

Those values were on display at a conference in May to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the center, which trains early-career researchers and provides a place where theoretical scientists — defined as those who use mathematics to study the natural world — can tackle the biggest questions in science, from the search for dark matter to global climate simulations to theories of quantum gravity.

"The range of topics presented at the PCTS@ten conference demonstrates that we've reached the goal we set 10 years ago, which is to develop a new breed of theorists with a much broader view of science than they would normally get from typical postdoctoral training," said Paul Steinhardt, Princeton's Albert Einstein Professor in Science and the center's director since 2007.

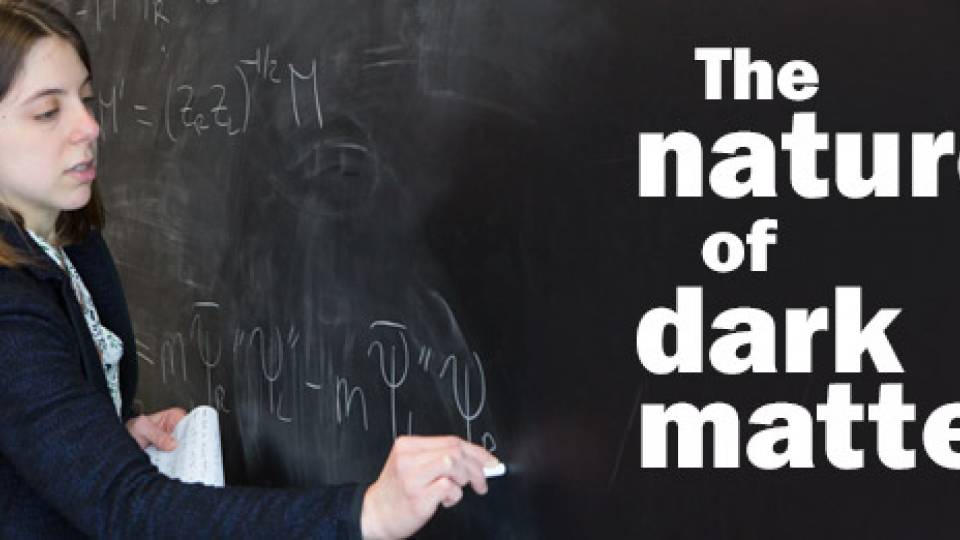

Mariangela Lisanti, a Princeton assistant professor of physics at Princeton, talks about her research on methods for detecting dark matter particles during the PCTS@ten conference in May, which celebrated the 10th anniversary of the Princeton Center for Theoretical Science. (Photos by Mark Czajkowski for the Office of the Dean for Research)

Steinhardt was instrumental in setting up the PCTS with inaugural director, Curtis Callan, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of Physics.

"Theoretical science involves the construction of mathematical frameworks that allow one to organize and understand complex data," Callan said, "and in a data-rich world, the use of these frameworks is growing. Today one can measure the activity of thousands of genes. If we want to understand what a living cell is doing over time, we need ways to organize the things we've learned, and this is at the heart of theoretical science."

The use of mathematical frameworks originated in physics departments, Steinhardt said, but the practice has since spread to other areas. "The theoretical mode of thinking can be found in biology, chemistry, geophysics and many other areas," Steinhardt said. "There might be some differences in jargon depending on the particular subject, but the basic ways of thinking are the same."

Titus Neupert (left), an associate research scholar who is finishing his three-year postdoctoral period at PCTS, was one of three outgoing postdoctoral fellows whose research was represented by a cake decorated with designs drawn from their research. At right is PCTS director Paul Steinhardt, Princeton's Albert Einstein Professor of Science.

The center opened in 2006 as the Princeton Center for Theoretical Physics with significant funding from a Princeton alumnus. In 2008, Callan and Steinhardt changed the name to the Princeton Center for Theoretical Science to reflect the center's reach beyond physics. The center moved into its current space, a renovated wing on the fourth floor of Jadwin Hall, in 2008.

Before 2006, theoretical scientists at Princeton were siloed in buildings and disciplines, with few opportunities to interact, Steinhardt said. At the PCTS, researchers can connect at workshops and seminars, and at the blackboards that line the nooks within the center's common room. "It is the little conversations at coffee breaks or at lunch that lead to connections, and those lead to new ideas and collaborations," Steinhardt said.

Weekly lunch meetings offer opportunities for PCTS researchers — which consist of postdoctoral researchers and faculty members — to give updates on their work. "They have to talk about their research in a way that others outside their area of science can understand," Steinhardt said. "It is very hard to find such an activity on any campus anywhere; seminars are usually by nature very narrow in focus."

Since its inception, the center has trained more than 30 postdoctoral fellows, so-called because they have finished their doctoral degrees and require some years of independent work before being ready to become faculty members. They are chosen via a rigorous process that starts with a nomination by their Ph.D. adviser. The top applicants come to campus to give talks, and a panel of PCTS faculty fellows chooses the finalists.

PCTS faculty fellows come from a range of Princeton departments, including chemistry, physics and astrophysical sciences, as well as the School of Engineering and Applied Science. The faculty fellows often conduct research with the postdoctoral fellows as well as mentor them. In addition to Steinhardt and Callan, the faculty fellows are Igor Klebanov, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics; B. Andrei Bernevig, associate professor of physics; Garnet Chan, the A. Barton Hepburn Professor of Chemistry; Pablo Debenedetti, the Class of 1950 Professor in Engineering and Applied Science and Princeton's dean for research; Eve Ostriker, professor of astrophysical sciences; Howard Stone, the Donald R. Dixon '69 and Elizabeth W. Dixon Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering; and Herman Verlinde, professor of physics.

In addition to conducting independent research, the postdoctoral fellows and Princeton faculty across the campus organize conferences that draw experts from around the world. "PCTS has become a very well-known place on the worldwide map of theoretical science because we have regular workshops and conferences that bring in people from all over the world," said Klebanov, the center's associate director and himself a theoretical physicist. "It gives the postdoctoral fellows a big boost for them to invite the best people in the field, meet them, and collaborate with them. Our hope was that PCTS would stimulate the intellectual life on Princeton campus and beyond, and I think it went well beyond expectations."

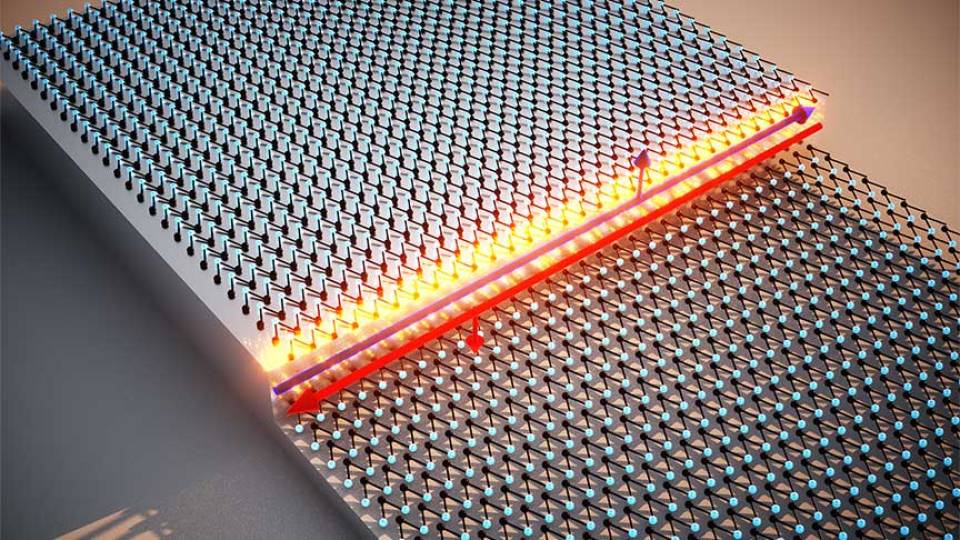

Another aspect that has gone beyond expectations is the accomplishments in science that the center has enabled. One such area is condensed matter physics, in which scientists study how solids and liquids form from the basic building blocks of atoms and their interactions. Princeton University has become a leader in the study of materials known as topological insulators, which have properties that could enable a new generation of electronic applications.

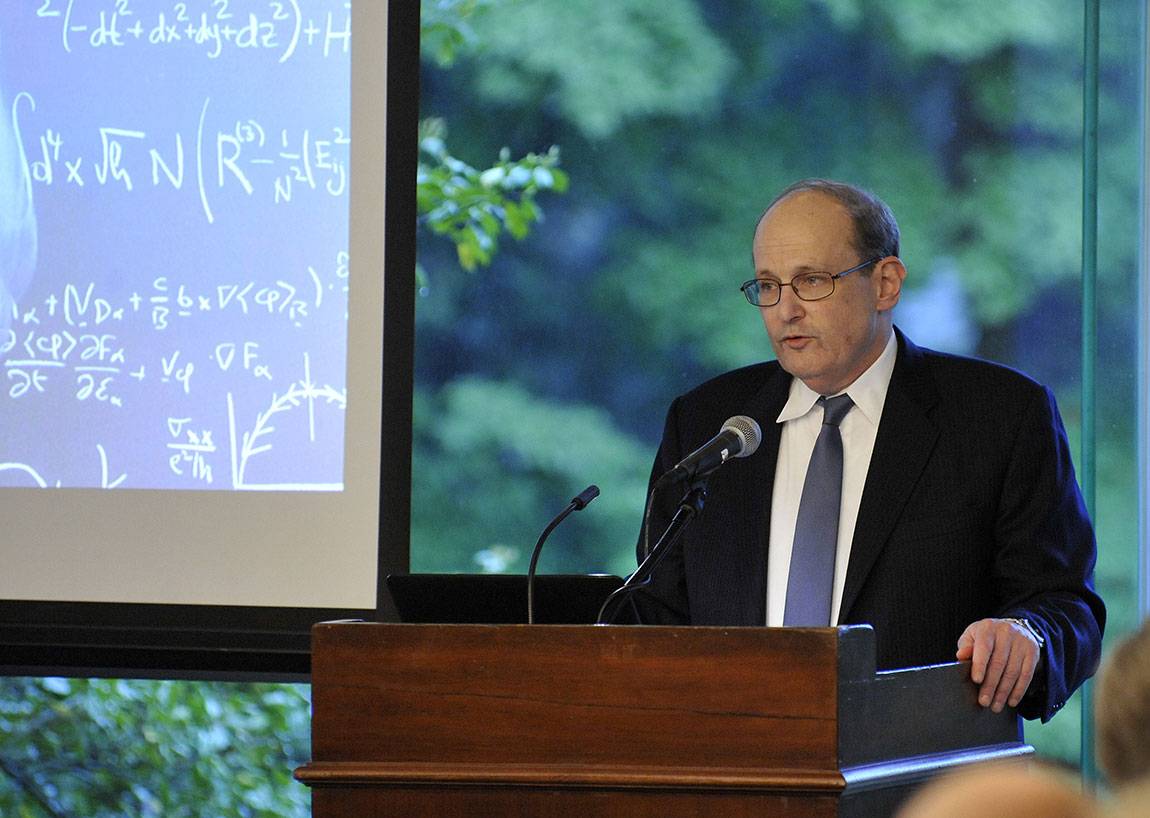

At a dinner celebrating the center's anniversary, Steinhardt talks about PCTS' accomplishments and future. The center brings together theoretical scientists for workshops and seminars, and trains early-career researchers using theoretical methods in a range of disciplines.

Associate Research Scholar Titus Neupert is a PCTS postdoctoral fellow finishing his three-year stint, during which he studied the quantum-mechanical behavior of electrons in solids, including topological insulators. One of the long-term outcomes of this research may be the building of a topological quantum computer, which could make calculations standard computers cannot.

"PCTS was an ideal place for me to 'grow' as a researcher and to learn about the cutting-edge problems that people in other fields are exploring," said Neupert, who will be starting his own research group as an assistant professor in the physics department at the University of Zurich this month. "It was great to be able to work with many different research groups in Princeton, across departments. The barrier to walking into someone's office and asking questions is lower than anywhere else."

The center also offers the "intellectual critical mass" to start new projects and new research, said Bernevig, who was in the first cohort of PCTS postdoctoral fellows accepted into the program in 2006 and is now on the Princeton faculty. "I believe that what PCTS does best is to offer complete freedom to the center postdocs. If a postdoctoral researcher wants to focus on one topic, she or he can do that. If on the other hand, she or he wants to focus on several topics, and explore different areas of research, including new fields, that is certainly allowed and encouraged as well."

Another former PCTS postdoctoral fellow on the Princeton faculty is Mariangela Lisanti, an assistant professor of physics who studies the astrophysical evidence for dark matter particles. "During my time at PCTS, I was encouraged to take risks and to explore entirely new research directions," she said. "I took that encouragement to heart and stepped beyond my immediate research area through collaborations with PCTS faculty fellows and postdocs. In that process, I discovered an entirely new field of interest, which today makes up a significant portion of my research efforts."

Other topics presented by postdoctoral fellows at the anniversary conference included research that could eventually lead to improved solar cells to capture energy from the sun, advances in fusion as a source of safe and renewable energy, how hurricanes affect global climate, and how nature controls the unfolding of a flower.

"We are now starting to discuss further plans for the center," said Klebanov. "We are not going to stand still."