Mark Edwards (foreground right), a lecturer in religion, leads a study group on Gandhi with residents inside Garden State Youth Correctional Facility (GSYCF) in Crosswicks, New Jersey. Edwards will teach a spring freshman seminar using residents' writings and reflections drawn from this experience.

Mark Edwards, a lecturer in religion at Princeton, will teach the spring freshman seminar “Imprisoned Minds: Religion and Philosophy from Jail,” using writings from residents inside Garden State Youth Correctional Facility (GSYCF) in Crosswicks, New Jersey, where he recently led a study group on the ethics and actions of Mahatma Gandhi.

The study group met weekly for six weeks. The program, “Discovering Gandhi in Prison,” was part of the 2019 Being Human Festival, coordinated by the Humanities Council in partnership with the Program for Community-Engaged Scholarship (ProCES).

Over the past few years, Edwards, also an adjunct professor at Princeton Theological Seminary, has held study groups inside GSYCF on Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s “Gulag Archipelago,” Hannah Arendt’s “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” and the autobiographies of Malcolm X and the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Below, Edwards reflects on his experience.

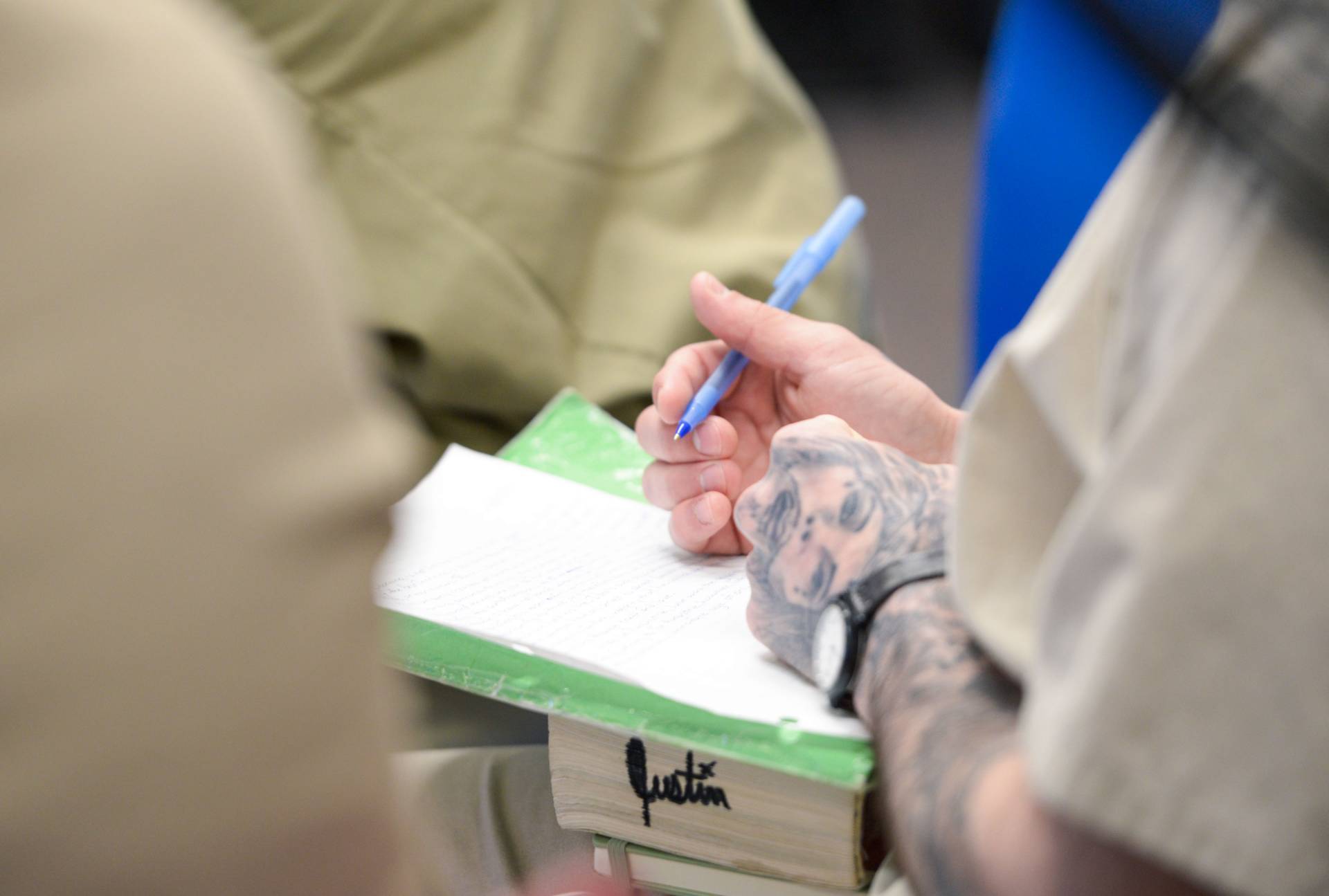

A resident takes notes during a study group session. The six-week program, "Discovering Gandhi in Prison," was part of the 2019 Being Human Festival, coordinated by the Humanities Council in partnership with the Program for Community-Engaged Scholarship (ProCES).

Week #4

“Why can’t this be your ashram?” It is a question I’ve posed to the study group. We have been reading Gandhi’s “Story of My Experiments with Truth.” After four weeks of reading, questioning and seeking Gandhi’s wisdom, the question seems natural. After my experiences these past few years leading study groups at Garden State, what I was actually thinking was, “Hasn’t this already become a kind of ashram?”

Week 4 was a key week in which we saw the genealogy of four terms charting the progression of Gandhi’s great soul: brahmacharya, satyagraha, ahimsa and ashram.

Brahmacharya is a vow of total celibacy and sexual purity in deed, word and thought. Having served as a stretcher bearer for shattered bodies in the Boer War and the Zulu “Rebellion,” Gandhi abhorred the British machines of destruction and turned inward. He asked himself, How are the abuses and violence which I detest in the British also flowing in my own lusts and habits with Kasturbai, my wife? He concludes, “Life without brahmacharya appears to me to be insipid and animal-like.” After consulting his wife, he makes the vow. Having made this first hardest choice, the “hard and steep” path ahead opened up.

Satyagraha is Gandhi's call to let one’s life become united with the force of truth. Satyagrahis unite under the pledge of ahimsa — the truth that non-violence is the way to overcome darkness, hatred and fear of death. With the realization that ahimsa is manifested in manifold ways, an ethic of “do not trample” leads Gandhi to change his dress, deny life insurance, and live off peanuts, lemons and olive oil. He rejects the caste system, adopts days of silence and with a pinch of salt liberates 350 million Indians living under the dehumanization of British colonial rule. Gandhi's philosophy of ahimsa creates the ashram, simple farming collectives of Satyagrahis who live, pray and suffer together.

Edwards and the group meet in one of the facility's common rooms. Over the past few years, Edwards, also an adjunct professor at Princeton Theological Seminary, has held study groups inside GSYCF on Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s “Gulag Archipelago,” Hannah Arendt’s “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” and the autobiographies of Malcolm X and the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Week #5

“Are you sure you really want to leave? It’s pretty crazy out there.” I pose this question to Chris and Tim, both scheduled for release this afternoon. Chris is ready to be out of here. But by the way Tim and his friends gather to talk, listen and pray, I can tell my question has actual import with him, even after 51 months. When an institution of unwilling segregation, isolation, incapacitation and punishment becomes a community of fellowship, books and wisdom seeking, a community one reluctantly leaves, maybe true reform has taken place? Perhaps an ashram has sprouted.

We are in prison. Should this be happening here? A fifth term of Gandhi’s legacy emerges: mandir — a Hindu temple. Perhaps this is the deepest truth Gandhi has to offer: “Suffering, cheerfully endured, ceases to be suffering and is transmuted to ineffable joy.” Time and time again Gandhi goes to jail with joy and in freedom. “The cell door,” he writes, "is the door to freedom.” Let there be no confusion. He is talking about going in. He spends 249 days in South African jails; 2,089 in Indian ones. These days are spent writing books, studying the scriptures and in quiet prayer. Back home on the ashram, even his private bedroom is cell-sized with bars on the windows. He calls prison his mandir; his temple to truth.

Week #6

Our last session. A photographer comes to capture what reading Gandhi in prison looks like. This changes the dynamic somewhat. What does it look like? Look and see. But let me say what it feels like. It feels like we are just being human. Hands holding books. Minds asking questions. Souls seeking a way.

An ashram? Let’s call it an experimental ashram cultivating the inner freedom of being human. Perhaps, it’s even a six-session ashram illuminating Gandhi’s conviction that “jail for us is no jail at all.”