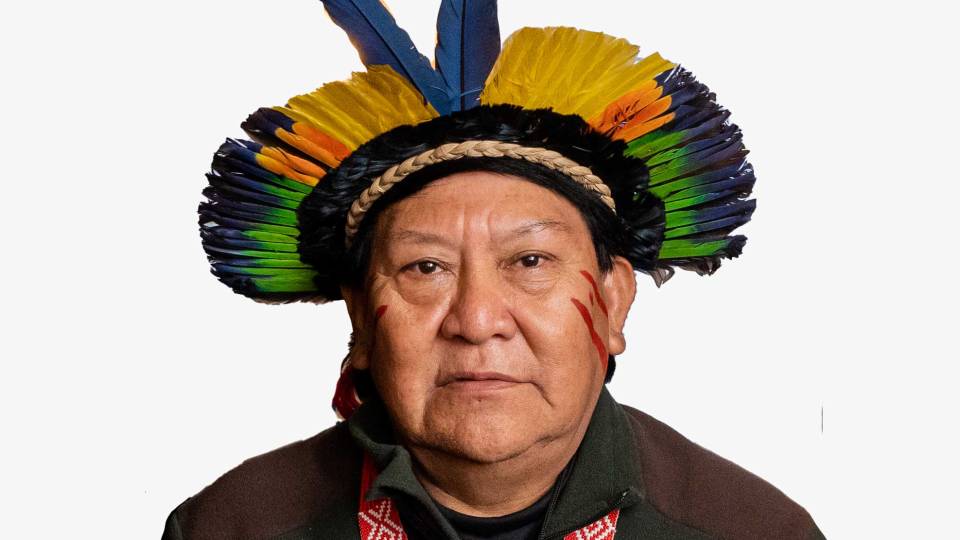

Olga Ulturgasheva, a renowned anthropologist and member of the Eveny reindeer herding community in northeastern Siberia, is teaching at Princeton this year about the interconnectedness of humans and the environment as the Canadian Studies Pathy Distinguished Visitor.

Arctic Indigenous worlds, experiences, and challenges past and present — along with their implications for our climate crisis — are the focus of a course at Princeton this spring titled “Pluriversal Arctic.” That is also the life’s work of the course’s instructor, Olga Ulturgasheva, an Eveny member, renowned anthropologist and the current Canadian Studies Pathy Distinguished Visitor at Princeton.

Ulturgasheva’s research is steeped in her lived experience, as well as academic study. She regularly returns to Siberia to conduct ethnographic research among Indigenous reindeer herders and their reindeer.

“I’m trying to show this alternative vision, perhaps change a little bit of something within these students, to see the environment not as something to control, tame or modify, but as something that without which, humans cannot survive,” said Ulturgasheva, an internationally recognized social scientist with decades of field research in the Arctic who is also a visiting research scholar and visiting professor in the Council of the Humanities for the current academic year.

“This entire course is about producing a particular subjectivity, which is about protection of the environment,” she said, “but also understanding the kind of worldviews that do not separate nature and culture in a way where nature is inferior to human culture.”

The Eveny, an ethnic minority and community of about 20,000, live in Northeast Siberia, in the Sakha Republic of Russia. While it remains the coldest inhabited place on Earth, their homeland is experiencing some of the most dramatic impacts of climate change.

Siberian permafrost — ground that is frozen year-round — is melting rapidly, making parts of the region uninhabitable as potential flooding looms and the land turns to mud and loses stability.

In June 2021, a temperature of 88.8 degrees was recorded in Oymyakon (which is accustomed to lows approaching or exceeding 80 below zero). Also in 2021, Siberia’s Yakutia region was among the hardest hit worldwide by forest fires. These fires were the largest ever recorded anywhere on Earth.

The changes threaten not only the Arctic, but the entire globe.

Research and lived experience

Ulturgasheva’s course incorporates both her lived experience and her research, introducing Princeton students to anthropological and cross-disciplinary studies of the ways in which circumpolar populations experience, perceive and respond to environmental, political and socioeconomic changes.

“The course is a primary source introduction to Indigenous knowledge, ways of looking at the world from a non-human centric perspective,” Ulturgasheva explained.

Ulturgasheva, who holds a Ph.D. in anthropology and polar studies from the University of Cambridge, is senior lecturer in social anthropology at the University of Manchester. She has carried out ethnographic research on childhood and adolescence, narrative and memory, animist and nomadic cosmologies, reindeer herding and hunting, climate change and the latest environmental transformations in Siberia and Alaska.

Since 2006, she has been engaged in international projects exploring climate change and adaptation patterns in Siberia, the American Arctic and Amazonia, along with human and non-human personhood, and youth resilience.

She also serves as a principal investigator for two large, international collaborative research projects funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the European Research Council (ERC).

At a reception in October, Ulturgasheva traded gifts as a symbol of friendship and solidarity with Pastor John Norwood of the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation. Princeton University sits on land that is considered part of the ancient homelands of the Lenni-Lenape peoples, who were the first inhabitants of eastern Pennsylvania and parts of New York, New Jersey, Maryland and Delaware.

The NSF-funded project is a study of adaptation strategies and resilience patterns among Alaskan Yup’ik and Siberian Eveny, which aims to provide new insights on human capacity to navigate through recent environmental threats induced by climate change and environmental degradation in the Arctic.

The ERC-funded project examines how climate change is managed at the ethnic borderlands of China and Russia, while mobilizing the expertise of anthropologists, historians and philosophers of science and ethics, religious studies experts, Indigenous leaders and environmental scientists.

Simon Morrison, professor of music and Slavic Languages and literatures at Princeton, and director of the Fund for Canadian Studies, encouraged Ulturgasheva to apply for the Pathy professorship after meeting her during a PIIRS Global Seminar, which he taught for 15 Princeton students in Moscow in 2019.

Morrison said Ulturgasheva’s research is grounded in her lived experience and her direct observations as an anthropologist.

“She’s looking at how people in her community are processing these calamitous events, and what she brings to the classroom is what it’s like to be there,” Morrison said. “She’s not just talking about stuff she read on JSTOR or in books. It’s actually the gritty, sweaty, uncomfortable, brittle, fragile, alienating nature of that kind of work.”

He added: “On one hand, she is committed to the preservation of that rich and distinguished and very fragile culture, and, on the other hand, she’s dealing with ways for us to comprehend something that’s existential and comprehensible — climate change — and whether or not there are systems of knowledge that Indigenous communities can provide, that can actually help us to comprehend and perhaps address the crisis.”

Twenty-seven Princeton students are enrolled in Ulturgasheva’s course this spring. About two-thirds are anthropology concentrators, and there are also students from departments as varied as music, computer science, mathematics and physics.

Ulturgasheva is teaching the course “Pluriversal Arctic” this spring to 27 students, introducing them to Indigenous ways of knowing, Arctic Indigenous cosmology, and how these can be used as lenses for viewing the world — in particular, our current climate crisis.

Ulturgasheva acknowledges that some of the source material can seem overwhelming and unfamiliar to students with different worldviews. Pluriversal in the course’s title, for example, refers to the theory of the existence of more than one reality, which is central to Arctic Indigenous cosmologies.

In one class lecture, Ulturgasheva described the central role of the shaman to Siberian communities in connecting with the spirit world and ensuring the health and well-being of the clan.

The term shaman, meaning “one who knows,” derives from the Tungus language, which the Eveny share with their closest kin, the Evenki. She played a video clip of a shamanic ceremony, and later spoke of the threats to shamanic practice, including the long persecution of shamans under Soviet Russian rule.

Keely Toledo, a concentrator in anthropology, was among the many students who engaged Ulturgasheva with questions afterward. Toledo, a member of the Navajo Nation, asked about how shamans protect themselves in the spirit world. “She doesn’t create an air of mystery about it,” Toledo said. “It’s a way of life.”

Toledo said Ulturgasheva encourages students to ask questions and to think critically. On a personal level, Toledo said she finds Ulturgasheva’s presence to be a comfort.

“She really does stand in her power, and I think that’s very inspiring,” Toledo said. “She believes in the work that she’s doing, and her passion shows through.”

Gabriel Duguay, a senior who is finishing an independent study in Indigenous studies, said he was thrilled when he learned the class was being offered.

Duguay, a Canadian national whose father is Mi’kmaw, said he and Ulturgasheva share many interests. Duguay said he hopes to work in the Arctic in the future for the Canadian government.

“I think her firsthand stories of the Arctic are pretty exceptional and really add to the issues that we’re talking about,” Duguay said. “Whenever we’re talking about a concept, she’s able to elaborate on it from personal experience which was really quite helpful.”

Ulturgasheva will share more lessons from the region later this year in a collection titled, “Risky Futures: Climate, Geopolitics and Local Realities in the Uncertain Circumpolar North” (Berghahn, August 2022). The volume, which she co-edited with Barbara Bodenhorn, brings together authors who are local practitioners, Indigenous scholars and international researchers, providing nuanced views of the social consequences of climate change and environmental risks.

The book takes up the same message she impresses upon her students: What happens in the Arctic region, such as permafrost thaw or methane release, not only sweeps rapidly through local ecosystems, but also has profound global implications.