Daniel Osherson, Princeton’s Henry R. Luce Professor in Information Technology, Consciousness, and Culture, Emeritus, and an emeritus professor of psychology, died at home in Princeton on Sept. 4 from complications due to Parkinson’s. He was 73 years old.

One of the world’s leading experts on cognitive science, Osherson did foundational work on reasoning, epistemology, inductive logic, probabilistic thinking, concepts and categories. He published two textbooks, “Sentential Logic for Psychologists” and “An Invitation to Cognitive Science.”

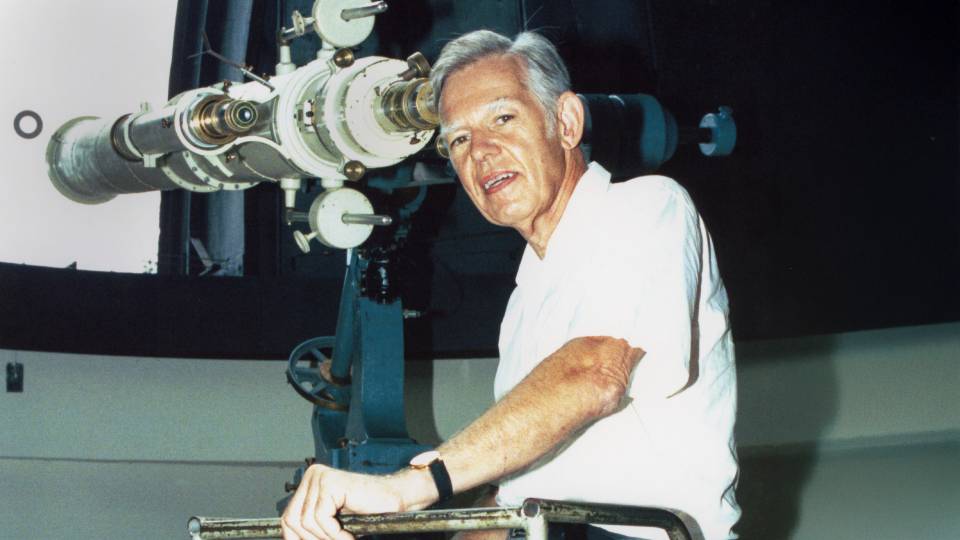

Daniel Osherson

“Dan was a cherished colleague and a legendary figure in cognitive science,” said Ken Norman, chair of the Department of Psychology and Princeton's Huo Professor in Computational and Theoretical Neuroscience. “He made important contributions to an incredibly diverse range of questions about human thinking, spanning from how we reason about probabilities to how concepts are represented in the brain. We will miss him terribly.”

Osherson’s passion for learning spanned several fields of expertise. “I found him to be a wonderful collaborator — very patient with my lack of knowledge of his field, and very quick in his understanding of mine,” said former Dean of the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences H. Vincent Poor.

Poor and Osherson collaborated several times. “These projects also involved some of my graduate students, and he was an excellent and caring mentor to them as well,” said Poor, Princeton’s Michael Henry Strater University Professor and the acting chair of the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. “I was serving as dean of engineering during this time, and he was very generous with his own time in working with these students when I wasn’t able to give them as much attention as they needed. I’m sure I won’t be the only one to say this, but he was a wonderful colleague, a great asset to Princeton faculty and students in multiple disciplines, and he will certainly be missed by many.”

“Dan had a broad range of interests in psychology, computer science, machine learning and philosophy,” said Sanjeev Kulkarni, former dean of the faculty and the William R. Kenan, Jr., Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering and Operations Research and Financial Engineering. "I have very fond memories of Dan and our collaborations."

Osherson joined Princeton’s faculty in July 2003 after a career that spanned academia and industry in Europe and several American states. He transferred to emeritus status in July 2017.

Never limited to a single discipline, Osherson studied jazz piano performance, linguistics and computer programming in addition to receiving his degrees in psychology. He received his B.A. from the University of Chicago in 1970 and his Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1973. He taught at Stanford University, UPenn, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Université Vita-Salute San Raffaele in Milan, and Rice University. He also spent four years as director of the Institute of Artificial Intelligence in Martigny, Switzerland, before coming to Princeton in 2003.

Noam Chomsky, a colleague at MIT, said that knowing Osherson was “a rare privilege.”

“Dan was a close personal friend for many years, a marvelous human being,” Chomsky wrote in an email. “A scientist of rare talent, exploring many domains with insight and original ideas, always demanding the highest level of intellectual integrity and consistently meeting his high standards in his own creative and often path-breaking contributions. It’s a cliché to say of someone that there are none like him. Sometimes it’s actually true.”

At Princeton, Osherson was known for his interdisciplinary research projects, which brought him into close collaboration with colleagues across the University.

“Dan and I were good friends for many years,” said renowned mathematical physicist Elliot Lieb, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics, Emeritus, and an emeritus professor of mathematical physics. “Despite coming from very different fields, we also collaborated on two scientific papers about concepts in neither one. Our collaborations opened mathematical vistas which I would not see otherwise and for which I am truly grateful.”

“Dan was a great friend, a wonderful person, and a brilliant scientist,” said Alexander Todorov, a former Princeton professor now at the University of Chicago. “In terms of science, he was interested in so many different topics, never losing his curiosity and always thinking outside the box.”

Osherson trained a number of influential psychologists and cognitive scientists in his career. One former graduate student who has become a prominent psychology researcher, Jiaying Zhao, described Osherson as her “intellectual father.”

“His mind was fiercely sharp, and he could spot the most critical flaw in any research in a manner of seconds,” said Zhao, who completed her Ph.D. in 2013 and is now an associate professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia. “Because of this, he made our work infinitely more rigorous. Since I started my lab at UBC, I often ask myself ‘What would Dan think?’ as a way to channel his criticisms to improve my work.”

“Dan was also incredibly supportive and warm to me as a supervisor,” Zhao said. “When I first arrived at Princeton from abroad, he brought me a landline telephone so I could make and receive phone calls. We met on an almost daily basis for five years to discuss work, life or anything else.”

Several of Osherson’s students spoke of his blend of scientific rigor and warmth.

Matt Weber, who completed his Ph.D. with Osherson in 2009 and is now the deputy chief data officer for the New Jersey Attorney General’s Office, wrote, “Dan taught me the value of replicable data analysis, the importance of sticking up for your subordinates, a healthy skepticism for machine learning, and the joys of an observation just terse enough to make the reader work a little.”

He continued: “He was usually funny, sometimes snarky, and always kind, and if I never forget the grueling Saturdays in his dark office fighting over tiny details of phrasing in a paper, I’ll also never forget that he pitched me a tough-sounding question at my defense that he knew I knew the answer to. Or the terror his index finger inspired in a generation of grad students — it would rise, solo, if he had a question about your talk, and more often than not, the question would (in the nicest possible way) cut right to the heart of what you were doing and why, and afterward you could tell your friends you’d gotten ‘oshed.’”

Eldar Shafir, who was Osherson’s Ph.D. student at MIT and is now Princeton’s Class of 1987 Professor in Behavioral Science and Public Policy, wrote: “Dan was a brilliant man; an original and independent thinker, with a dry sense of humor and a sharp moral sensibility. An eternal student, he cultivated so many interests — from learning theory, child development, thinking and decision making, and perception, to theoretical computer science, biology, and world affairs. Dan approached all of these with striking intensity and an innovative and often inspired touch. I remember as a graduate student first going to meet this august figure who had a reputation for being scary-smart. To my surprise I found a warm, funny and quirky renaissance man in an office whose walls he kept perfectly bare. Dan would become my teacher, my mentor and my dear friend. He lived the examined life, and those of us who felt close to him benefitted from his smarts, his humor and his warmth. I’ll miss him deeply.”

Scott Weinstein of the Class of 1969, a frequent collaborator and close friend since they were young faculty together at UPenn, praised the breadth of Osherson’s work across the many subdisciplines of cognitive science, from laboratory studies of the effects of traumatic brain injury on cognition, to the mathematical foundations of machine inductive inference. “Throughout this work, his creativity in framing research problems — and his energy and enthusiasm for pursuing their resolution — inspired the efforts of numerous students and colleagues as collaborators,” he said.

“Among my many precious memories of Dan as collaborator and friend, one that stands out now is our miles-long walks around Manhattan,” said Weinstein, now the director of the Logic, Information, and Computation Program at UPenn. “Dan had a deep interest in history and culture, and he would vibrantly bring to life the landscape and milieu of the neighborhoods we traversed from decades and centuries earlier. Recollections of Dan’s enormous lust for life, his towering intellect, and his extraordinary openness and generosity of spirit, bring joy to my heart, even amidst my grief in his passing.”

Michael Miller, then a graduate student in politics, was one of Osherson’s early collaborators at Princeton. “In a University full of world-class scholars, Dan was a legend among the graduate students, someone talked about with head-shaking amazement and surprise at the sheer range of his interests and mastery of it all,” said Miller, who completed his Ph.D. in 2011 and is now an associate professor of political science at George Washington University. “I was lucky enough to co-author with him when I first started as a student, and it transformed my approach to research. Dan didn’t talk about writing papers like it was work; he talked about it as discovery, as a chance to uncover knowledge long buried or never known.”

Joseph Blasi, the director of the Institute for the Study of Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing at Rutgers and a former visiting professor at Princeton, first crossed paths with Osherson when they were both in Cambridge in the 1970s; for the past decade, they have been neighbors in Princeton.

“Dan was the sweetest of colleagues and the most tolerant of others throughout those many years,” Blasi said.

Their 50-year friendship included a little-known chapter of Osherson’s life: “Many of Dan's recent colleagues do not know about his deep and energetic involvement in the seventies to found a liberal arts college focused on cooperative principles called the Cooperative College Community,” Blasi said. “The college came very close to reality. After he moved next door to me in Princeton, we would often discuss and analyze those days, in typical Dan fashion!”

Osherson is survived by his wife, Yolande, and their three children: Marc, his wife Neetu Agrawal and their daughter Adele; Anne and her partner Carlos Monino; and Benjamin.

Donations may be made to any foundation working on Parkinson’s research.

View or share comments on a blog intended to honor Osherson’s life and legacy.