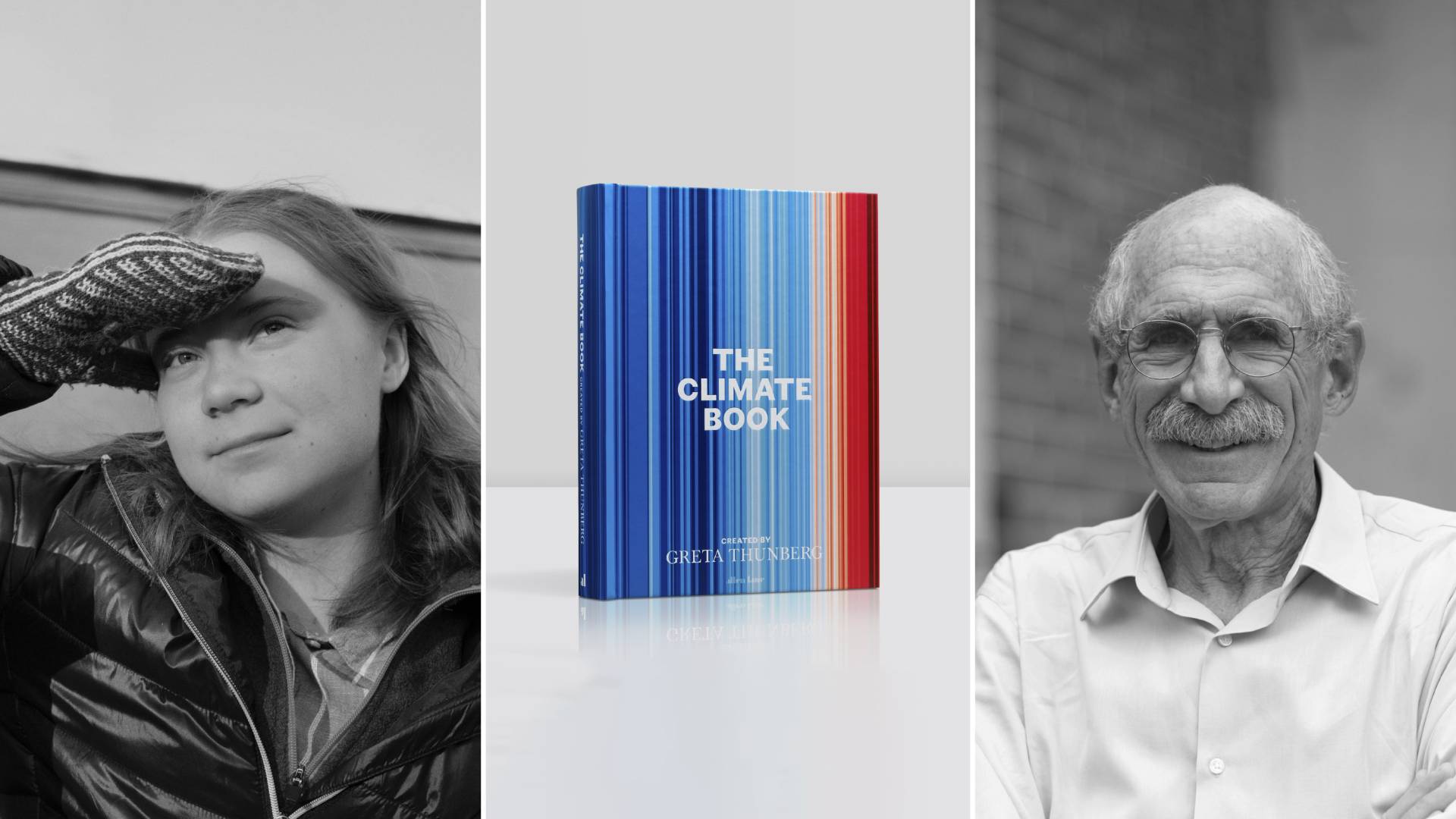

Greta Thunberg, The Climate Book, Michael Oppenheimer

Princeton climate scientist Michael Oppenheimer first came to the attention of climate activist Greta Thunberg in 2019, the year of the children’s strike that made the Swedish teenager a household name across the globe.

Thunberg's team reached out to him after the release of an influential report on the world’s oceans that Oppenheimer coauthored for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and they stayed in touch.

This year, Oppenheimer is one of 100 expert contributors to Thunberg’s new anthology, “The Climate Book: The Facts and the Solutions” (Penguin Random House), which was published in the U.K. Oct. 27 and is slated for U.S. release in February. Oppenheimer’s essay, “The Discovery of Climate Change,” appears in the book’s first section, under the heading “The science is as solid as it gets.”

Here, he talks about what makes Thunberg so compelling as an activist, what he likes about the book’s approach to climate change, and why he hasn’t given up on humanity’s ability to fix this “terrible mess” that we’ve gotten ourselves into.

Oppenheimer is the Albert G. Milbank Professor of Geosciences and International Affairs and the High Meadows Environmental Institute, and director of Princeton’s Center for Policy Research on Energy and the Environment. This interview has been edited and condensed.

First and foremost, how did you come to be part of this book? How did you come to know Greta Thunberg?

I was an author on the 2019 report for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change about sea level rise, oceans and ice, and I did a lot of work to make sure the IPCC report got as much publicity as possible in the United States. I think that brought me to her attention.

Her people asked me to appear at an event with her in Washington. I couldn't make it, but they remained in contact.

Greta distinguished herself by ultimately making the science and scientists a touchstone for her message. She sent a handwritten thank you note to the scientists of the IPCC.

Her work brought together my own interest in science, in activism and the IPCC. I decided if she asked me to do something, I would do it. And then they asked me to contribute to the book.

Thunberg has grown to global prominence as an activist. What makes her successful?

She strips away unnecessary complexity and gets the whole thing down to a direct and coherent message, and she’s unabashed in pointing to those responsible.

It’s as if she is able to stand outside of the complexity of the issue — not deny it, but actually go to the very essence. That is, that the scientists are telling us something, that they’ve been telling us for over 100 years, we haven’t been listening, and now we’re starting to pay the price.

The appearance of naiveté draws people in, and the wisdom knocks them on the head. And, to my knowledge, she’s never said a thing about the science that’s wrong.

How did the science and its timing contribute to her success?

There were a lot of things that came together in the 2015-2019 period that gave her a lot to work with. The governments had asked for an IPCC report on the 1.5-degree Celsius target in the Paris Agreement. If that report hadn’t come out, and there wasn’t something particular for her to point to, it might not have worked.

There had also been a string of “bad weather,” which had grabbed people's attention, building on concern generated by the deadly 2003 heat wave in western Europe, and Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and Hurricane Sandy in 2012 in the U.S. In 2017, Hurricane Harvey struck, and the science had advanced enough to be able to attribute the phenomenal rainfall totals in the storm to the buildup of greenhouse gases.

Attribution science’s first success was quantifying the contribution of climate change to the intensity of the 2003 European heat wave, and by the time Greta was ready to make her public move, it had become widely accepted science. You could say “the precipitation in that storm was 40% higher because of climate change,” or “that heat wave in the Pacific Northwest could not have happened without the climate change caused by the buildup of greenhouse gases.” Statements now could be very firm and clear.

What have you learned from her?

She reminded me that speaking with clarity and speaking the truth about what the science says can be powerful when there is an adept messenger. And she’s a very adept messenger.

What’s different about this book?

What you’re getting here is the personal take of individuals on the issue, speaking largely from their professional perspectives. Those individual prisms are put in a juxtaposition, which lets the reader get a much more comprehensive picture than they usually get, yet at a level they can understand.

Usually, you get either what one person thinks about an issue or a chaotic picture because too many people are involved and there is no central message. Instead, in this book Greta’s vision holds it together.

It goes through different views on how climate change happened in the first place, developments that might allow us to do something about it, the forces of opposition that aren’t going away that we have to deal with, and the forces that are pushing forward. So you get all that, but not from any one person. It is well constructed, without the different perspectives warring with each other.

How have you able to detach from the scariness of climate change to persist over your long career? Can you talk about that?

I’m old enough that when I was in elementary school, it wasn’t like life was great because it was the 1950s, it was like, we are all going to die in a nuclear exchange with the Russians.

I clearly remember in the third or fourth grade being told to get under my desk, cover up my head and eyes. We had to practice in the case of a nuclear explosion. It was even worse than, “Climate change is going to get out of control and we won’t know what to do”; it was like, “We’re going to be vaporized.” The fact that we weren’t and I’m still alive is a bit of a surprise.

What that tells me is that human beings are very adept at making terrible crises happen, but they are almost always smart enough to get out of the crises.

Unfortunately, they usually wait too long. But I am convinced that human beings are capable of both making terrible messes and cleaning them up.

They are always a little slow on getting to the cleaning up. But now we’ve gotten going, so we’re going to get it fixed.

And that’s not the whole story. My father was a refugee from Hitler. He grew up in a world that is far worse than what I’m facing or what my kids are facing. It was terrible — half his relatives were murdered. He got over here, survived and thrived. Certain things you just have to get through, and hope that things will be better on the other side. I am not going to live long enough to see the climate problem really solved, but hopefully my children will.

Can you characterize this moment in climate history?

Well, I will say I’m sick of seeing moments identified as, “This is it.” While it’s not the end if you screw up, because you can usually come back and try again, the more times we fail to really get the solution to climate change off the ground, the harder it gets for people to thrive, particularly for those who don’t have a lot of resources. We can’t let the warming continue to run out of control again and again. We’ve got to try harder.

Still, might this be one of those pivotal moments that could really get us going, if we redouble our focus on climate change? I think it is, because the public’s attention won’t stay riveted on climate forever. We have to get certain things in place to ensure that solving the problem becomes routine and is just a part of the way we do everything.

We’re in the midst of an energy revolution. That is happening. Will it be perfect? No. Are we still going to have damaging climate events caused by the warming happening for decades? Yes. But we’ll hopefully learn how to deal with it. Are we going to learn how to deal with it in a way that will help the victims of the junk we’ve put into the atmosphere over the last couple centuries? I hope so.