Name: Rubén Gallo

Title: Associate professor of Spanish and Portuguese languages and cultures, director of the Program in Latin American Studies

Scholarship: A scholar of modern Spanish America, Gallo is the author of "Freud's Mexico: Into the Wilds of Psychoanalysis," forthcoming from MIT Press, which explores Freud's relation to Mexico. His other publications in English include "Mexican Modernity: The Avant-Garde and the Technological Revolution," which won the Katherine Singer Kovacs Prize in 2005, and "New Tendencies in Mexican Art."

Gallo is the 2009 Fulbright-Freud Visiting Lecturer in Psychoanalysis and is spending the fall in Vienna as a guest of the Sigmund Freud Foundation, located at Berggasse 19, where Freud lived for 47 years before emigrating to London after the 1938 annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany. Gallo has an office in the room that was once the bedroom of Minna Bernays, Freud's sister-in-law. In addition to conducting research at the Sigmund Freud Museum, he is giving a series of lectures on Freud's relation to Mexico and teaching a seminar at the University of Vienna.

How did a scholar of modern Spanish America become interested in Freud?

For the past three years I have been writing a book on Freud and Mexico. Part of it is about the reception of Freud. Who was reading Freud in the 1920s? How were books like "Totem and Taboo" read by Mexican poets and artists? Part of it is about Freud's view of Mexico. Freud collected Mexican antiquities, read Mexican books — in Spanish — and corresponded with Mexican disciples. Surprisingly, no one had explored this intriguing relationship. There are books about Freud in Russia, Freud in France, even one about Freud in Argentina called "Freud in the Pampas," but there was virtually nothing about Freud in Mexico, so I decided it would make a good book project.

Has living in Vienna helped you understand Freud's relationship to Mexico?

Absolutely! Not many people realize that the histories of Austria and Mexico have been intertwined for more than 500 years, and that the two countries have had a complex — and at times traumatic — relationship. It was a Hapsburg King, Charles V, who ruled Spain during the Conquest of Mexico in the 1520s, and many of the Aztec treasures taken by the Spaniards made their way to Vienna, where they can still be seen today. And in the 19th century, during one of the most surreal episodes of history, another Austrian, Maximilian von Hapsburg, the younger brother of Kaiser Franz Josef, became emperor of Mexico. He was shot by a firing squad in 1867 — a scene that was painted by Manet — despite pleas to the Mexican government by figures including Victor Hugo and Queen Victoria. And in 1938, Mexico was the only country to present a formal protest at the Society of Nations against the Nazi annexation of Austria, the event that led to Freud's exile. To commemorate this expression of solidarity, Vienna named one of its squares "Mexikoplatz" after the end of the war.

Living in Vienna has helped me to understand the relations between these two cultures, and it inspired me to write a chapter called "Freud's Mexican Vienna," where I document all the "Mexican" places Freud would have encountered during his daily walks in the city.

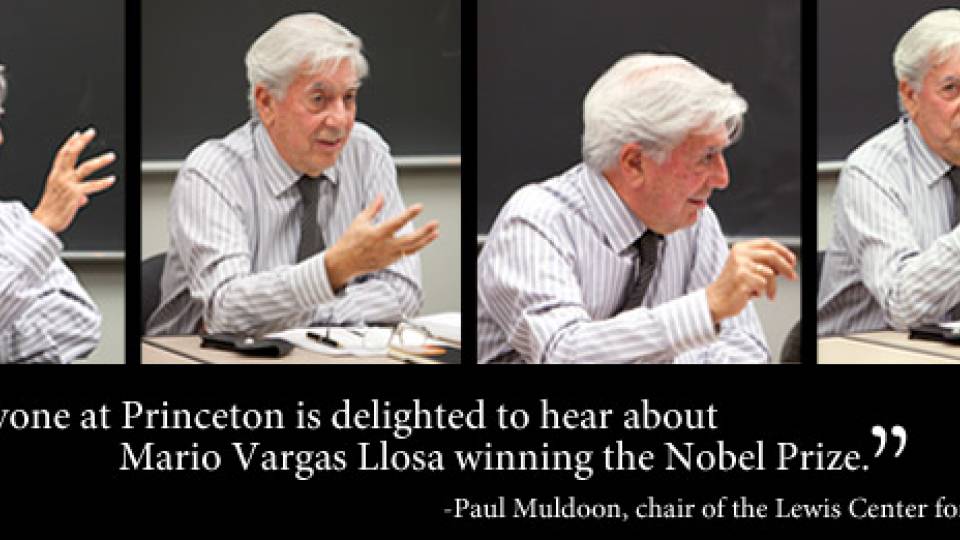

In addition to conducting research at the Sigmund Freud Museum (shown here), Gallo is giving a series of lectures on Freud's relation to Mexico and teaching a seminar at the University of Vienna. He said the experience of living in Vienna has helped him understand the relations between the Austrian and Mexican cultures.

What is it like to work in Berggasse 19?

It is an extremely moving experience. The first time I entered the doorway and walked up the stairs to Freud's apartment, I thought to myself: This is the birthplace of so many ideas that transformed the world. So much of 20th-century culture — the talking cure, surrealism, the films of Luis Buñuel, our approach to the study of literature at Princeton, everything down to the humor of New Yorker cartoons — trace their origin to this modest apartment in Berggasse. And what strikes me most is to think that Freud altered the course of history without weapons, money or power; all he had were ideas and words. It was his passionate relation to "the life of the mind," as Hannah Arendt called it, that changed the world — and it was all done from a desk in this very apartment.

What is a typical day like for you in Vienna?

I have a quick breakfast in my apartment, where from my window I can see the Stefansdom, Vienna's cathedral. I then head to the National Library, located in a section of the Hofburg, the Imperial Palace, where I read and write for most of the day — this is the beauty of a sabbatical year. In the evenings I usually attend lectures at the university or at the Sigmund Freud Museum; the last talk I heard was by an economist who did a psychoanalytic study of "Overconfidence and the Financial Markets." And a few times a week I have dinner at one of Vienna's famous cafés, like the Landtman, or go to a concert at the Philharmonic.

Do you expect to teach about this work when you return to Princeton?

Yes! I already have a few ideas for courses. One will be "Freud at Large," a seminar devoted to the readings of Freud offered by artists and writers in Latin America. The other will focus on the literary and artistic representation of the execution of Maximilian. Mexican novelists have been fascinated by this episode since the 19th century, and there is a vast corpus of novels, plays, poems, paintings — even an opera — that tells us much about the relationship between literature and history.