Jason Petta, an assistant professor of physics, has found a way to alter the property of a lone electron without disturbing the trillions of electrons in its immediate surroundings. Such a feat is an important step toward developing future types of quantum computers. (Photos: Brian Wilson)(Images for news media)

* Read about another Princeton University-led team making advances in spintronics *

A major hurdle in the ambitious quest to design and construct a radically new kind of quantum computer has been finding a way to manipulate the single electrons that very likely will constitute the new machines' processing components or "qubits."

Princeton University's Jason Petta has discovered how to do just that -- demonstrating a method that alters the properties of a lone electron without disturbing the trillions of electrons in its immediate surroundings. The feat is essential to the development of future varieties of superfast computers with near-limitless capacities for data.

Petta, an assistant professor of physics, has fashioned a new method of trapping one or two electrons in microscopic corrals created by applying voltages to minuscule electrodes. Writing in the Feb. 5 edition of Science, he describes how electrons trapped in these corrals form "spin qubits," quantum versions of classic computer information units known as bits. Other authors on the paper include Art Gossard and Hong Lu at the University of California-Santa Barbara.

Previous experiments used a technique in which electrons in a sample were exposed to microwave radiation. However, because it affected all the electrons uniformly, the technique could not be used to manipulate single electrons in spin qubits. It also was slow. Petta's method not only achieves control of single electrons, but it does so extremely rapidly -- in one-billionth of a second.

"If you can take a small enough object like a single electron and isolate it well enough from external perturbations, then it will behave quantum mechanically for a long period of time," said Petta. "All we want is for the electron to just sit there and do what we tell it to do. But the outside world is sort of poking at it, and that process of the outside world poking at it causes it to lose its quantum mechanical nature."

In his laboratory, Petta has trapped one or two electrons in microscopic corrals created by applying voltages to miniscule electrodes on a wafer of semiconductor.

When the electrons in Petta's experiment are in what he calls their quantum state, they are "coherent," following rules that are radically different from the world seen by the naked eye. Living for fractions of a second in the realm of quantum physics before they are rattled by external forces, the electrons obey a unique set of physical laws that govern the behavior of ultra-small objects.

Scientists like Petta are working in a field known as quantum control where they are learning how to manipulate materials under the influence of quantum mechanics so they can exploit those properties to power advanced technologies like quantum computing. Quantum computers will be designed to take advantage of these characteristics to enrich their capacities in many ways.

In addition to electrical charge, electrons possess rotational properties. In the quantum world, objects can turn in ways that are at odds with common experience. The Austrian theoretical physicist Wolfgang Pauli, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1945, proposed that an electron in a quantum state can assume one of two states -- "spin-up" or "spin-down." It can be imagined as behaving like a tiny bar magnet with spin-up corresponding to the north pole pointing up and spin-down corresponding to the north pole pointing down.

An electron in a quantum state can simultaneously be partially in the spin-up state and partially in the spin-down state or anywhere in between, a quantum mechanical property called "superposition of states." A qubit based on the spin of an electron could have nearly limitless potential because it can be neither strictly on nor strictly off.

New designs could take advantage of a rich set of possibilities offered by harnessing this property to enhance computing power. In the past decade, theorists and mathematicians have designed algorithms that exploit this mysterious superposition to perform intricate calculations at speeds unmatched by supercomputers today.

Petta's work is using electron spin to advantage.

"In the quest to build a quantum computer with electron spin qubits, nuclear spins are typically a nuisance," said Guido Burkard, a theoretical physicist at the University of Konstanz in Germany. "Petta and coworkers demonstrate a new method that utilizes the nuclear spins for performing fast quantum operations. For solid-state quantum computing, their result is a big step forward."

Petta's spin qubits, which he envisions as the core of future quantum logic elements, are cooled to temperatures near absolute zero and trapped in two tiny corrals known as quantum wells on the surface of a high-purity, gallium arsenide chip. The depth of each well is controlled by varying the voltage on tiny electrodes or gates. Like a juggler tossing two balls between his hands, Petta can move the electrons from one well to the other by selectively toggling the gate voltages.

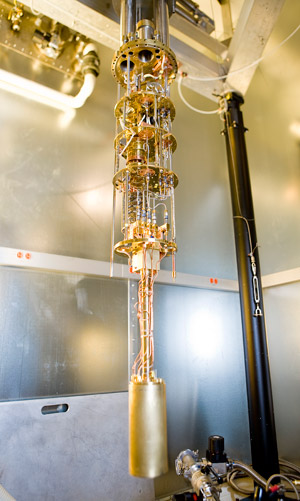

Spin qubits, which could be the core logic elements of quantum computers, are cooled in a device called a dilution refrigerator to temperatures near absolute zero in order to exploit the mysterious rules of quantum mechanics.

Prior to this experiment, it was not clear how experimenters could manipulate the spin of one electron without disturbing the spin of another in a closely packed space, according to Phuan Ong, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics at Princeton and director of the Princeton Center for Complex Materials.

Other experts agree.

"They have managed to create a very exotic transient condition, in which the spin state of a pair of electrons is in that moment entangled with an almost macroscopic degree of freedom," said David DiVincenzo, a research staff member at the IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, N.Y.

Petta's research also is part of the fledgling field of "spintronics" in which scientists are studying how to use an electron's spin to create new types of electronic devices. Most electrical devices today operate on the basis of another key property of the electron -- its charge.

There are many more challenges to face, Petta said.

"Our approach is really to look at the building blocks of the system, to think deeply about what the limitations are and what we can do to overcome them," Petta said. "But we are still at the level of just manipulating one or two quantum bits, and you really need hundreds to do something useful."

As excited as he is about present progress, long-term applications are still years away. "It's a one-day-at-a-time approach," Petta said.

Research at Princeton was supported by the Sloan Foundation, the Packard Foundation and the National Science Foundation. Work at the University of California-Santa Barbara was supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the NSF.