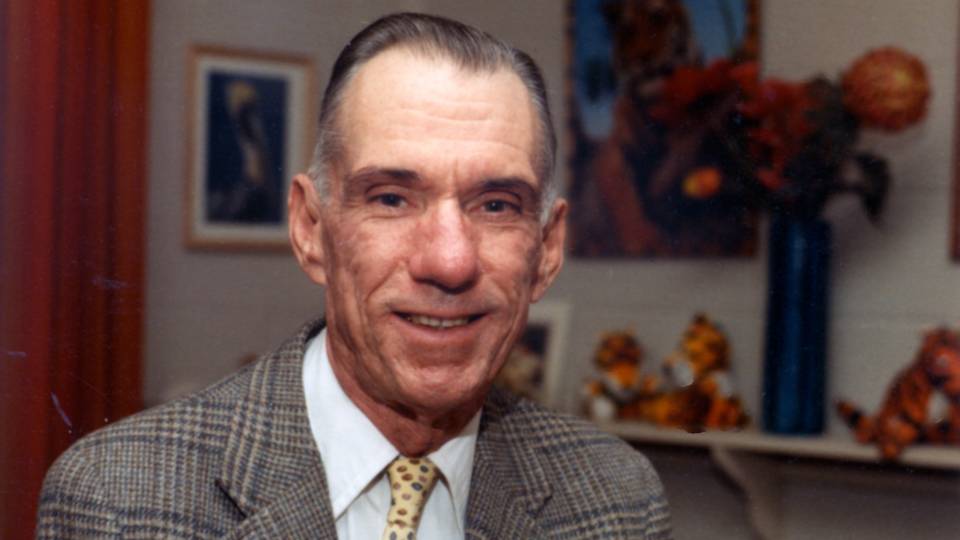

Sin-I Cheng, an emeritus professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Princeton University who, in a career spanning five decades, made critical early advances in rocketry and helped develop modern computational approaches to aerodynamics, died Dec. 6 at his home in Princeton. He was 89.

Cheng, who earned his Ph.D. in aeronautical engineering from Princeton in 1952 and served on the University faculty for 41 years, developed an early expertise in the stability of liquid propellent rocket engines. He published a highly influential monograph in 1956 with his thesis adviser, Professor Luigi Crocco, describing the fluid dynamics and chemistry that could lead to overly rapid or explosive burning.

The theoretical understanding provided by this rigorous work was essential in paving the way for reliable rockets as the United States hurdled into the space race after the Sputnik launch of 1957, said Sau-Hai "Harvey" Lam, who was a graduate student at Princeton at the time and is now the Edwin S. Wilsey Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Emeritus.

"In the early days, rockets very frequently blew up on the test stands," Lam said.

In subsequent years, Cheng made broad contributions to fluid dynamics, the field that includes understanding the flow of fast-moving gases, such as air over a wing. He published more than 100 journal articles and book chapters on subjects such as unsteady boundary layers, reacting gas dynamics, high-speed flows and turbulence.

Working as a consultant to industry, Cheng helped develop early designs for intercontinental ballistic missiles. In 1973, Cheng was granted a patent on a method for reducing the sonic boom associated with airplanes that travel beyond the speed of sound.

As computers became more prevalent in research, Cheng was an early proponent of using them to simulate fluid flows to solve problems in aerodynamics and develop a deeper, mathematically based understanding of turbulence.

Cheng was born in Changzhou, China, and scored first in the nation in his college entrance exams, which earned him a full scholarship to a Chinese college of his choice. He earned a bachelor's degree in 1946 from the prestigious Jiao Tong University in Shanghai. In another nationwide competitive exam during his senior year, Cheng also scored exceptionally highly, winning him a government-sponsored scholarship to pursue advanced studies abroad, a rare opportunity during those war years.

Cheng enrolled at the University of Michigan in 1948 and received his master's degree in aeronautical engineering the following year. He came to Princeton in 1949 as one of the first recipients of a highly competitive national fellowship, the Daniel and Florence Guggenheim Jet Propulsion Fellowship. At Princeton, he was one of the first Ph.D. candidates in a newly created department, then called the Department of Aeronautical Engineering.

Cheng was appointed an instructor at Princeton in 1951, prior to earning his Ph.D., and was promoted after graduating in 1952 to research associate with the rank of assistant professor. He was awarded tenure in 1957 and promoted to the rank of full professor in 1960. Cheng retired from full-time teaching and research in 1992 but actively continued his work on the theoretical foundations of turbulence.

In recognition of his work, Cheng was named an honorary professor at Northwest (Xibei) University in Xian, China, and honorary director of the university's Thermophysics Institute. He also was a visiting professor and consultant to the National Cheng Kung University in Tainan, Taiwan.

Following normalization of relations between the United States and China, Cheng frequently returned to China under Chinese government invitations to deliver lecture series at universities and research centers across the country. Under the auspices of the United Nations (UNESCO), he delivered an influential series of lectures in Dalian, China, in 1979 on computational aerodynamics.

Cheng also was a founding participant in a visiting scholars program that brought Chinese graduate students and young professors to study temporarily in the United States and which is credited with leading to structural improvements in the Chinese educational system.

Combining skepticism and enthusiasm

Ronald Probstein, who earned his Ph.D. in the department the same year as Cheng, said that as a student and later as a faculty member Cheng was both brilliantly quick and painstakingly careful in working through new ideas.

"He would really work to understand a new idea," said Probstein, now the Ford Professor of Engineering Emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "Where many of us would accept it and move on and use it, Sin couldn't do that. Unless he could understand it to the last T, he would just stay on it until he did."

"Years later, if we talked about a particular problem [we had solved] he was still skeptical about the approach we used," Probstein said.

A former student of Cheng's, Sylvain Raynes, said that having Cheng as his thesis adviser was a formative experience in his career.

"The most important thing I took away was a skepticism toward what is," said Raynes, who earned his Ph.D. in 1986 and went on to a career in finance. "Whatever you read in a book may not be the whole unadulterated truth. So you must question — you must go into things in a deeper way than what is presented to you. That was Professor Cheng's own approach to everything."

Raynes noted that although he himself moved away from the field of fluid dynamics, he stayed in contact with Cheng, who worked until his death on his longtime dream of creating exact mathematical equations — as opposed to methods based on statistics — to describe turbulence. Raynes said this work was largely completed and he had helped Cheng secure a book contract before Cheng's death.

Lam, who had Cheng as an adviser when he first joined the department, recalled that Cheng's passion for his subject was infectious.

"The thing that I remember was his enthusiasm," Lam said. "He was the one who imparted not only the subject matter itself, but the beauty of the subject when he taught."

Another student at the time, William Sirignano, recalled particularly enjoying a two-semester graduate course Cheng taught on the subject of viscous fluids. "He would lose track of the clock and stay overtime, but I didn't have any class afterward, and he was just a very good lecturer," said Sirignano. "His enthusiasm was always contagious."

Sirignano also joined the faculty at Princeton and later became dean of engineering at the University of California-Irvine. Cheng was a supportive senior colleague, Sirignano recalled. "He made a younger colleague feel important."

Cheng is survived by his wife of 65 years, Jean, as well as his three surviving children, Doreen, Andrew and Irene, seven grandchildren, and two great grandchildren. Another son, Thomas, died in 2008. Cheng's sons and three of his grandchildren also are Princeton alumni.

Memorial contributions may be made to the American Cancer Society to further the advancement of cancer research.