Princeton politics professor Christopher Achen (above) is co-author, along with Larry Bartels of Vanderbilt University, of "Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government," a book published in April by Princeton University Press that challenges popular conceptions of how American democracy works and lays the groundwork for a new approach. (Photos by Denise Applewhite, Office of Communications)

While on a fellowship at Princeton in the early 2000s, Christopher Achen wandered into a bookstore across from campus. On the front table he spotted two books about shark attacks along the New Jersey coast that killed four people over 12 days and sparked a panic in 1916.

Those books gave Achen an idea, a way to test a theory he and colleague Larry Bartels had been batting around as part of a broader conversation about the way American democracy does — and doesn't — work. The theory in question: American voters often blame incumbents for things the officeholders can't control. So, did the shark attacks cost incumbent President Woodrow Wilson votes in the 1916 election?

"I spent the next month down in the bowels of Firestone Library digging up the election returns for little coastal towns in New Jersey for 1916 and comparing them to 1912 and 1911, when Wilson ran for governor," said Achen, now the Roger Williams Straus Professor of Social Sciences and a professor of politics at Princeton. "I coded it up and ran it, and there it was, big as life. There's no question people voted against Wilson because of the shark attacks."

Achen and Bartels, Princeton's Donald E. Stokes Professor in Public and International Affairs, Emeritus, and the May Werthan Shayne Chair of Public Policy and Social Science at Vanderbilt University, spent 15 years testing such theories, analyzing voting patterns and filling in an outline first sketched on a dinner napkin. The result is a book published in April by Princeton University Press, "Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government," that challenges popular conceptions of how American democracy works and lays the groundwork for a new approach.

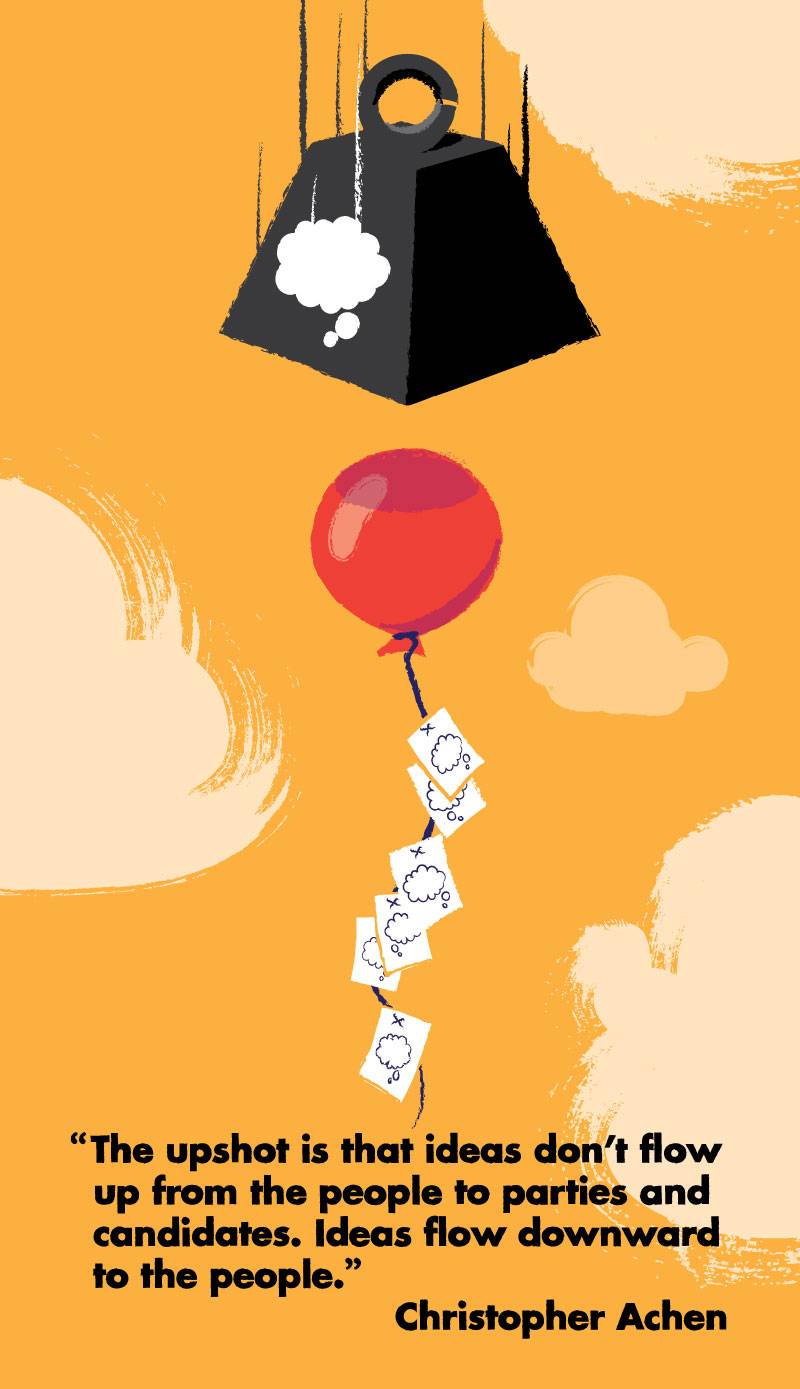

"The upshot is that ideas don't flow up from people to parties and candidates," Achen said. "Ideas flow downward to the people. Voters have loyalties and identities that are central to understanding what happens in elections. Parties and interest groups mobilize these identities and tell people how to think about their problems, as opposed to individual people selecting politicians based on the policy positions they prefer."

Challenging conventional wisdom

That conclusion challenges what Achen and Bartels call the "folk theory of democracy," which is the idea that voters have policy preferences and select candidates based on those preferences or — in cases of a referendum — voters make policy directly based on their policy preferences.

"That really, really doesn't work," Achen said. "People don't have the time and interest to follow issues, and they make serious mistakes and harm themselves in the process."

Achen said the approach to studying democracy he has crafted with Bartels highlights the inequality in American politics, where the preferences of individual voters don't play a significant role. (Illustration by Kyle McKernan, Office of Communications)

Bartels and Achen argue that a second prominent theory about American democracy also doesn't hold up. Known as the retrospective theory of voting, it suggests that voters hold sway by passing judgment on the performance of incumbents. As the shark attacks show, Achen said, voters struggle to do this effectively both because they blame incumbents for things they can't control and because voters tend to have a short time horizon, thinking back over only the past six months or a year.

While Wilson won re-election in 1916 despite the shark attacks, Achen said another presidential election turned on another factor unrelated to the candidates: the weather. In 2000, Achen and Bartels estimate, unhappiness over flooding that affected some places and drought in others turned enough voters away from Al Gore, the incumbent vice president, for George W. Bush to be elected president.

The new approach suggested by Achen and Bartels calls for political scientists to pay more attention to individual voters' social, occupational, racial and religious identities, rather than how voters come to hold particular policy positions. As an example, Achen points to supporters of Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, who has called for building a wall across the U.S. border with Mexico.

"We don't believe that large numbers of people have been desperately wanting to build a wall across the border with Mexico and have found a candidate who also believes that," Achen said. "We argue it's the reverse. Many of those who believe Trump will build the wall have gotten the idea from him. We're directing attention to the circumstances in those people's lives that the political system has not paid attention to — the economic struggles — that draw them to a candidate like Trump."

Achen and Bartels are already thinking about how they might expand on their ideas, continuing a relationship that began when Bartels studied under Achen as a graduate student at the University of California-Berkeley.

Achen himself earned his bachelor's degree at Berkeley before getting his Ph.D. from Yale University. He taught at Yale, Berkeley, the University of Chicago and the University of Michigan before joining the Princeton faculty in 2004. Achen, whose research interest is political methodology, has also written books including "Interpreting and Using Regression" and "The Statistical Analysis of Quasi-Experiments." He is affiliated with Princeton's Center for the Study of Democratic Politics.

"Professor Achen is one of the singular giants in the field of American public opinion and methodology," said Paul Frymer, a professor of politics. "He was at the forefront of a revolution in the way political scientists understand public behavior and his work remains the standard that newer scholars need to respond to. His new book, by all appearances, is a perfect addition to his already incredibly distinguished canon.

"But beyond that, they simply don't make people like Chris anymore, by which I mean that he's both an incredibly brilliant and talented scholar of political methodology as well as having unparalleled intellectual depth and breadth. "

Achen brings his research into the classroom, where he encourages students to look beyond policy positions supported by voters to understand their motivations.

Beyond policy positions

Topics Achen teaches undergraduate and graduate students include religion and American politics, democratic theory and practice, comparative political behavior, and the Tea Party and the history of populist movements in America.

Achen said he applied many of the approaches from his current research to his course on the Tea Party and populist movements, helping students look beyond policy positions advocated by the Tea Party movement to understand the movement's supporters.

"Their policy positions are what you hear," Achen said. "That's not necessarily the main thing to understand in my view, but rather how they think about themselves. You pay attention to how people construct their understanding of their life. They build a notion of who they are, what life is about, why they are a good person. They bring those structures to politics, and it brings them out in complicated ways."

Achen said this approach to studying democracy highlights the inequality in American politics, where the preferences of individual voters don't play a significant role.

"The current system is profoundly unequal in how it treats people and profoundly unequal in the access and clout that it gives people," he said.

Eve Barnett, a member of the Class of 2016 who took the Tea Party course in the fall of 2014, said the course and Achen's teaching changed her perspective on what it means to be a political scientist.

"He showed me that political science isn't only about explaining what happened, but it's also about understanding why it happened," said Barnett, who is majoring in politics and pursuing a certificate in values and public life. "Professor Achen demanded rigorous analysis and gave us all the intellectual tools we needed to do just that. That class helped me discover how challenging and invigorating the field can be — and how much I love it."

Barnett explored the organizational structure of the National Park Service in her senior thesis, with Achen as her adviser.

"He helped me take my thesis from an idea to the most challenging, rewarding project I have ever had the pleasure to complete," she said. "At each stage of the process when I came up with questions and concerns, he said something along the lines of 'if this were an easy project, Eve, it wouldn't be a worthwhile one.'"

That's much the same reason Achen said he and Bartels kept working on "Democracy for Realists" over many years.

"We want to get people to think about how democracy works in a different way, to see the places in which it's very unequal," Achen said.