This fall, a Princeton instructor charged students with brainstorming some highly creative improvements to the Palmer Square shopping district. They were warned to avoid the commonplace.

Almost all of them failed.

"The Palmer Square exercise has become famous, or infamous," said Derek Lidow, originator of "Creativity, Innovation and Design," the class that tested the students. The course, offered by the Keller Center, expects students to broaden their approach to design problems. As Lidow said, it teaches a series of skills that develop and flex creativity like a muscle group.

"The first time they go out, they all come back with one or two of the same insights. They are shocked. All of them," said Lidow, an entrepreneurial specialist and lecturer in electrical engineering who graduated from Princeton in 1973. "Even though we warn them. Even after four weeks of helping them get out of their mode of thinking like perfect business consultants."

By the time the students redo the lab one week later, Lidow said, they all "break through."

Derek Lidow, Class of 1973, is an entrepreneurship specialist and lecturer in electrical engineering and the Keller Center who encourages students to create and design solutions from a new perspective. (Photo by Frank Wojciechowski for the Office of Engineering Communications)

The Palmer Square lab is a mere warm-up. In the four years since its inception, "Creativity, Innovation and Design" has pitted undergraduates against some of Princeton's most intractable problems — "wicked problems," as they are called, which are unsolvable but can be mitigated — by teaching them to create and design solutions from a new perspective. The instructors tutor the students in a five-step process called "design thinking," and then assign them pre-selected wicked problems. The classes have dealt with, for example, student sleep imbalances, at-risk drinking, microaggressions and identity crises.

The class has succeeded far beyond Lidow's expectations. It has climbed from one class annually to four sections per year, drawing students from the arts and humanities as well as engineering and the sciences, and necessitated hiring a second lecturer, design expert and researcher Sheila Pontis. Graduates have gone on to work in product design, including at the design firm IDEO. Lidow, the founder and former CEO of iSuppli Corporation, rejects the idea that creativity and innovation cannot be taught. Instead, he regards them as skills developed through practice and "good coaching." The course, he said, is an amalgam of several design courses collapsed into one term that pushes students to evolve creatively.

From the beginning, Lidow envisioned University-wide participation. Administrators, deans, counselors and professors are involved in framing the problems, then judge which end-of-semester presentations most effectively mitigate the initial problem and could be implemented.

The University is now testing several recent designs. In one, a re-imagined breakfast experience that includes cartoons, game boards and a homier selection of food options aims to solve sleep imbalances by coaxing students to shift the start of their day.

Lidow asked another class to come up with plans to mitigate sexual-assault risks. Their solution, already implemented, included re-routing the TigerTransit bus to Prospect Avenue on party nights. The University installed brighter lighting on the bus and trained student volunteers to ride along and provide support. In its first six months, the system provided 1,923 rides. Of riders surveyed, 21 percent said they used the bus to get home safely, often due to alcohol consumption or to avoid someone seeking a sexual encounter. Some 16 percent took advantage of the peer counselors and many reported using the bus ride to rethink their plans for the balance of the evening.

A glance at the classroom in the Engineering Quad proves it serves no ordinary course. Desks are folded up or broken out as needed. Whiteboards on rollers surround or divide students. Storage bins contain rope, glue sticks, charcoal or duct tape as if awaiting some precocious kindergartener.

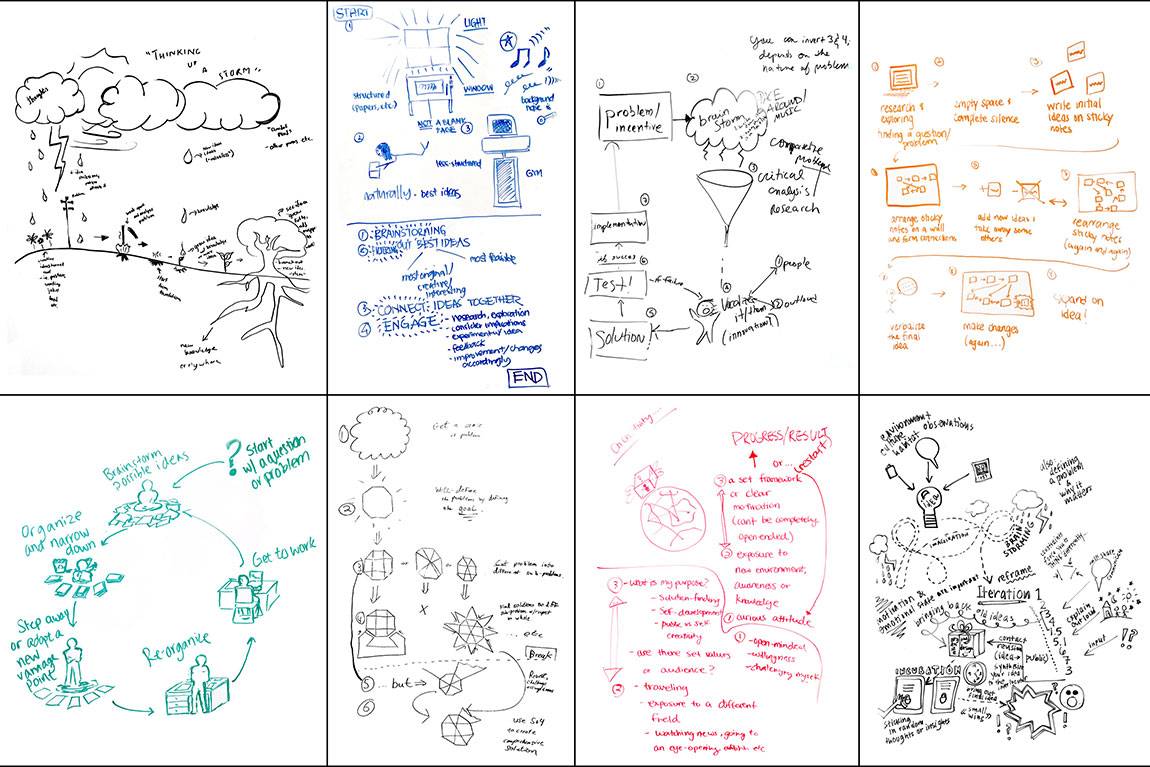

Students in "Creativity, Innovation and Design" taught by lecturer Sheila Pontis created these eight images when given 15 minutes to visualize their own creative processes using concepts they learned in class. (Image courtesy of Sheila Pontis, Keller Center)

Pontis said the specially designed class helps students tap the unconstrained creativity they indulged as children. Absent conscious effort, the brain is wired, she said, to minimize thinking differently and cognitive energy.

"I've learned that creativity and innovation do not happen in a vacuum," said senior John Morone, a computer science major whose section last year worked on microaggressions. "Thinking hard about a problem will not help you solve the problem by itself. The class did not focus on one set path to creativity. Instead, it laid out many workflows — each with infinite variations — and brought to our attention approaches that could unleash creative avenues."

Another former student in the class, junior Taylor Jones, said the course "helped me break out of a fixed mindset I didn't even know I had."

Combining classroom discussions with three-hour labs, the course paces students through a systematic approach: empathy or deep understanding of the problem, reframing, ideation or free association, prototyping, and testing. Students are graded in part on whether their end-of-term solutions are adopted by the University.

Students in the class pepper a panel of experts with questions on their assigned topic of identity crises. The panel returns at the end of the semester to review students’ designs for solutions. (Photo by Frank Wojciechowski for the Office of Engineering Communications)

"Today, problems are getting more complex and boundaries between disciplines are blurred," Pontis said. "I graduated almost 20 years ago when a designer just dealt with well-defined problems. Now, a designer tackles broader and unframed challenges.

"That change in mindset is tremendously valuable to students," she added. "This class helps students think differently and approach problem-solving in a creative way so that they are better equipped to solve complex problems facing society."

This story was originally published in EQuad News.