In the spring course “Derrida’s Library: Deconstructon and the Book,” students studied the French philosopher Jacques Derrida through a hands-on exploration of his personal working library, which was acquired by the Princeton University Library (PUL) in 2015.

Katie Chenoweth, an assistant professor of French and Italian, taught the course, which held many sessions in the PUL Division of Rare Books and Special Collections’ classroom within Firestone Library. Eleven students, a mix of undergraduates and graduate students, were able to delve into Derrida’s intellectual process by engaging with the rich assortment of annotated and carefully curated material the philosopher left behind as part of his literary legacy when he died in 2004.

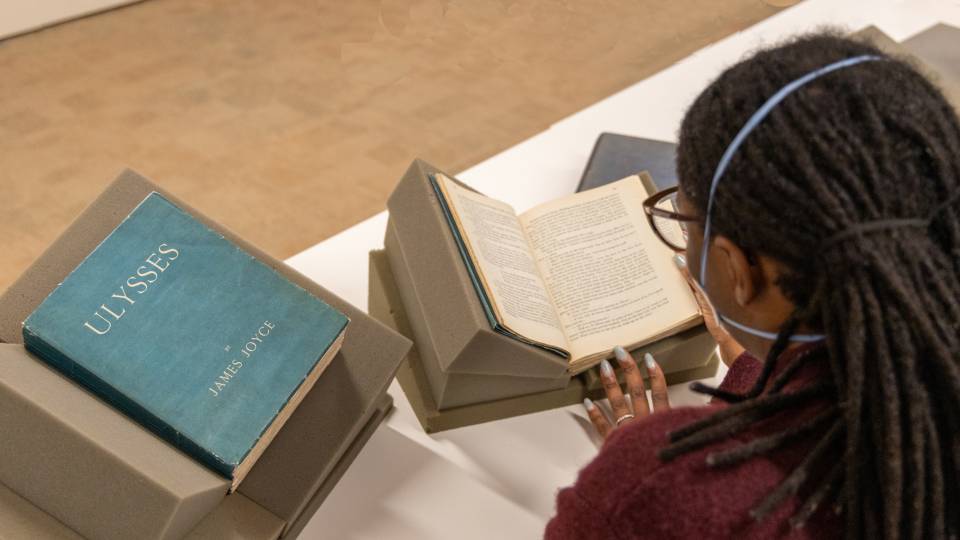

Library catalogers and archivists have spent the last three years processing Derrida’s collection, which consists of about 18,000 items, with 13,800 published books and other printed materials, as well as other objects. The cataloguing process was extensive, not only due to the sheer volume of the collection and detailed annotations, but because Derrida tucked many objects away among the pages of his books, said John Logan, a literature bibliographer in the PUL Division of Scholarly Collections and Research Services. Logan, who traveled with Chenoweth to France to see the collection before it was moved, said these included items such as postcards, photographs, letters, cartoons and even dried leaves.

“Derrida is a creator of texts, but text is not necessarily words in his case. It can be objects. All of these things are significant,” said Logan. “I think that Derrida was always aware of what he was doing and I think there’s perhaps an element of the very savant actor in him. He was a performer … so perhaps this is a quieter form of that same thing, performing in the book, on the book, through the book.”

In order to preserve the collection as it existed in Derrida’s library, catalogers assigned each of these articles its own catalog number.

“If you go into the library and you want to request a book, you never get just one book. You get an entire box,” said Chenoweth. “That box will often have books by the same author, books that were close to that one on the shelf, and you’ll have this whole kind of treasure trove where you get to discover other things, and not just the one thing that you thought you wanted to look at.”

The experience of working with an archive’s physical material has enhanced students’ understanding of Derrida’s work.

“The books [in the collection] are real, physical objects and they have a life of their own,” said Carlos Kong, a graduate student in the Department of Art and Archaeology.

For researchers who are unable to visit the collection at Firestone Library, Chenoweth and colleagues at the Center for Digital Humanities have developed Derrida’s Margins. The first phase of the website focuses on annotations related to Derrida’s landmark 1967 work “De la grammatologie” (“Of Grammatology”), with plans to expand the site’s offerings in the coming months.

Associate University Librarian for Scholarly Collections and Research Services David Magier worked with faculty members and the Derrida family to obtain the physical collection, and he said PUL has acquired rights to additional works, such as Derrida’s lecture notes, and is digitizing them to provide new avenues of research.

“Digital humanities often asks questions that you couldn’t answer just by reading a book or a set of books. It’s sort of aggregating lots of content in order to do some kind of understanding or analysis of the whole corpus or a whole library,” Magier said. “[Derrida] was using items from his library in preparation for his lectures. So he has annotations in the books that point to specific lectures he was going to give, and vice versa, his notes for the lecture would point to different things he was reading from his library. And drawing those intellectual connections is a wonderful project for these scholars.”