Rosina Lozano

Rosina Lozano, associate professor of history, researches Latino history with a focus on Mexican American history, the American West, migration and immigration, and comparative studies in race and ethnicity.

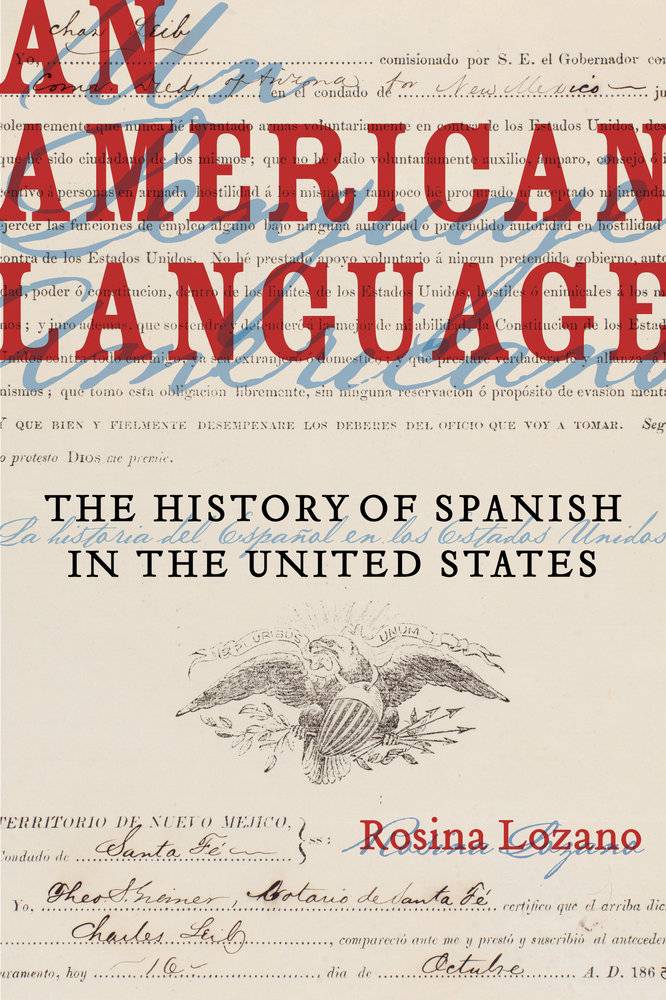

Her latest book, “An American Language: The History of Spanish in the United States,” published this year by the University of California Press, is a political history of the Spanish language in the United States from the incorporation in 1848 of the Mexican Cession — the region that Mexico ceded after its war with the United States — through World War II. It also discusses more recent developments.

In “An American Language,” Lozano argues that the United States always has been a multilingual nation, and that Spanish-language rights, in particular, have remained an important political issue to the present.

Lozano answered questions about Spanish’s little-recognized role in the development of U.S. history.

Lozano’s book, “An American Language: The History of Spanish in the United States,” examines the role Spanish played in the early years of the United States to the present day.

You describe Spanish as a colonial, immigrant and indigenous language in the United States. Can you explain that?

Social linguists have defined the Spanish language in this way. It is a colonial language because the Spanish colonized much of what became the United States. It is also an indigenous language in many parts of the current United States due to its over 400-year history of being used by Spanish settlers and Native peoples. The oldest capitol city in the United States is Santa Fe, New Mexico, which was founded in 1610. Since then, Spanish has — over time — become viewed by many in the United States almost exclusively as an immigrant language due to the millions of immigrants who have come in recent decades from Latin America.

How and why have Spanish’s roots in American history been forgotten?

If you grow up on the West Coast, the evidence of a previous Spanish-language past is all over in the place names of streets, towns and even states like Colorado. Most people know there are older roots, but they don’t know what happened with the language after the United States took over the lands that became the U.S. Southwest.

“An American Language” traces the largely forgotten history of the official use of Spanish in political settings in the states of the Southwest after the war with Mexico. This included having legislatures with translators, constitutional protections of translations at the state level, Spanish-language ballots, political speeches, court proceedings and schools. This history may have been forgotten, but it was never hidden. It was all over the archives once I began looking.

Why is it important that we acknowledge that history?

There are several reasons why the longer history of the use of Spanish in the United States is important. First, it demonstrates that a United States political system not only can, but has operated bilingually before. Second, it serves as a reminder that Spanish is not just an immigrant language in this country, but has very deep roots in the political culture of the nation. The federal government acknowledged the use of Spanish and even paid for translations of documents in New Mexico. It did very little in the 19th century to try and transition much of the Southwest into English.

As I give talks, I am also reminded that this history has a real value for individuals. It provides Spanish speakers with a way to connect with the history of the United States. They have told me that it makes them proud to know that the language they are often told is foreign has a longer history in the nation.

You make the argument that Spanish, from pre-colonial times through today, gained a privileged status over other languages in this country. How has it benefited?

The reasons that Spanish has held a privileged status have changed over time. In the 19th century, Spanish was the only language that the federal government supported financially by paying for translations of official territorial documents. It did so because instead of the Spanish language being a second language of government (like it was with German in several states), it was actually the language of politics. In New Mexico, the legislature and many of the courts operated in Spanish.

By the 20th century, Spanish gained incredible importance because it served the economic and political goals of the United States in Latin America. Spanish became the most studied non-English language in high schools and universities by World War II. At the same time that Spanish became important for hemispheric reasons, increasing numbers of immigrants also arrived from Latin America. This immigration has brought debates over its use in official settings at a broader scale.

How do your students respond to learning about the more complex racial and ethnic underpinnings of the nation’s founding?

The vast majority have never learned the history of everyday individuals in the United States and how they were affected by colonialism, war or immigration policy. Most high school textbooks only have a cursory discussion of these sorts of topics. Sometimes students get a little angry reading primary sources for class that cause them to draw different conclusions from the summaries that their high school textbooks provided because they wish they had learned this side of history sooner.

Learning the history of those everyday people who resided in the United States allows my students to connect the history of the United States to their own experiences.