To survive, organisms must solve a number of physics problems: converting energy from one form to another, detecting weak signals in a noisy environment, building structures that extend far beyond the natural scales of their building blocks and more.

For a physicist, understanding life means discovering and articulating the physical principles that govern these essential functions.

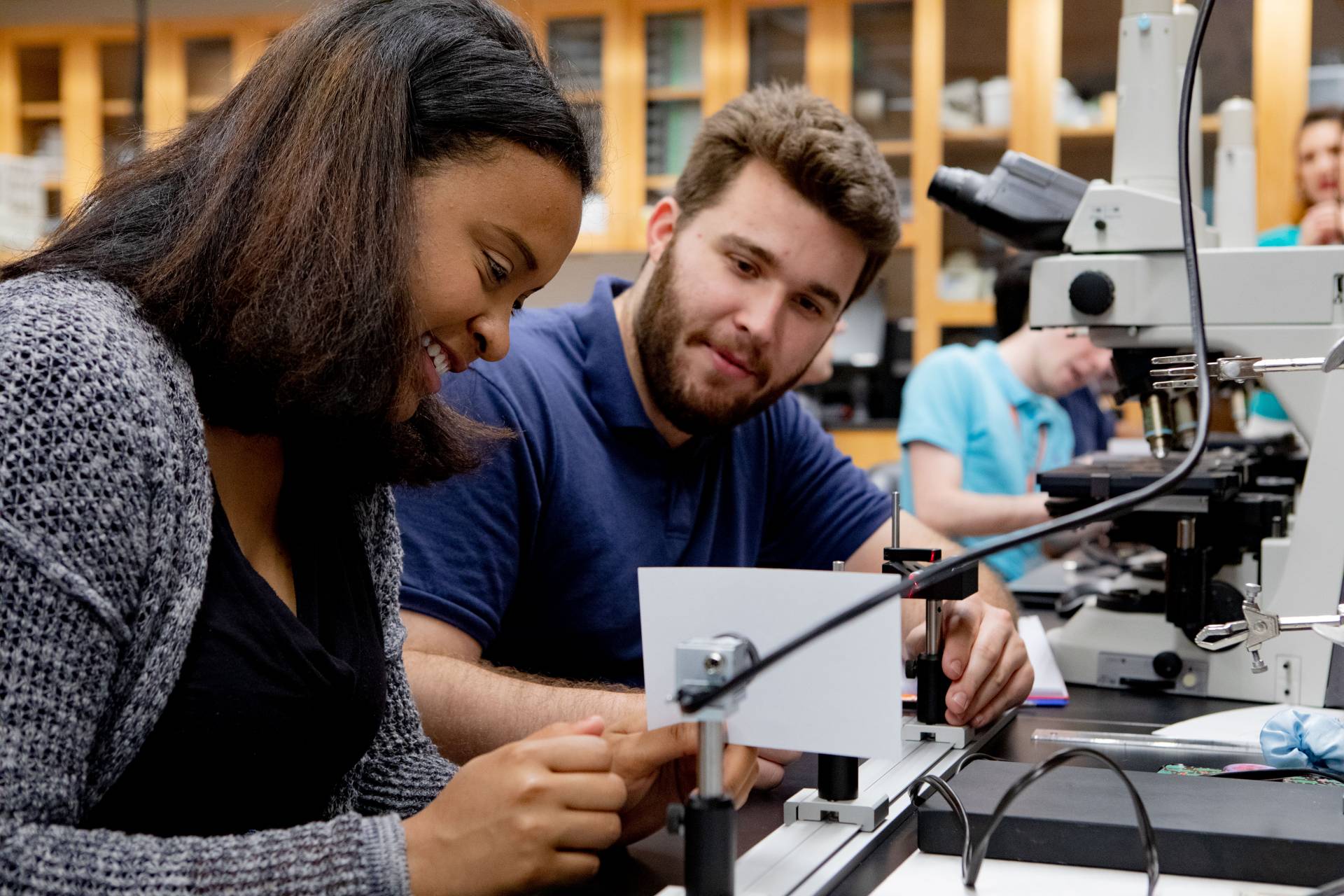

Physics and biology students from around the world came to Princeton for an intensive two-week summer school focused on the intersections between the disciplines, hosted by Princeton-CUNY’s Center for the Physics of Biological Function. Here, Victoria Lakshmi Antonetti of CUNY-Lehman College and Hunter Seyforth of California State University-Fullerton are participating in one of the program’s hands-on lab sessions, aligning their optical components to observe an Airy disk, the diffraction pattern that results from light passing through a small circular opening.

What would it mean for a generation of young scientists to have that bio-physical perspective?

That question, posed by the creators of the joint Princeton–City University of New York Center for the Physics of Biological Function (CPBF), led to the creation of a two-week intensive biophysics summer school for juniors and seniors from around the world, led by the 14 members of the CPBF faculty.

“If you spend your time trying to do science at the interface between physics and biology, you realize that the way we traditionally teach both disciplines is limiting for our students,” said William Bialek, the John Archibald Wheeler/Battelle Professor in Physics and the Lewis–Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics (LSI), who is one of the co-directors of the CPBF. “Princeton is special: We have a critical mass of faculty who work at the border of physics and biology. And not only is Princeton an institution that has tremendous resources, it’s also an institution that believes those resources are there to build an environment in which people get the best possible education.”

Now in its second year, the CPBF summer school brings students to campus to delve deeply into the space between biology and physics.

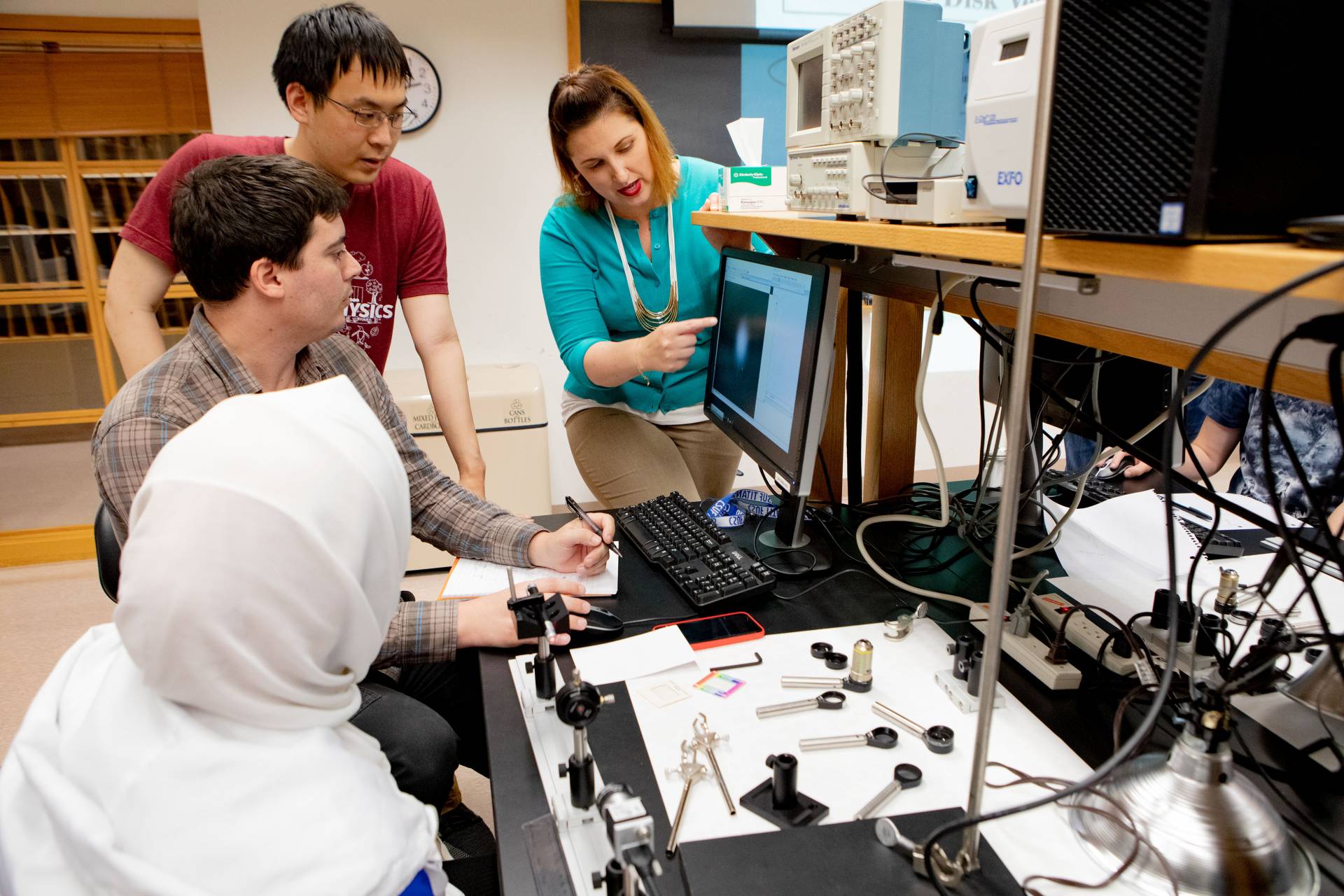

From left: Dianzhou “John” Wang from the University of Illinois-Urbana-Champaign works with Sara Al Bassri and Alex Vidal from Cal State-Fullerton to determine the wavelength of their laser, based on how much light is diffracted when passing through a grating.

“We think that the undergraduate time is a very nice time to do it,” said co-director Joshua Shaevitz, a professor of physics and LSI. “Physics students typically do not see biology in their education — and if they do go take a course in a typical biology department, I don’t think it’s easy for them to see the links to their physics education. So this is an opportunity to get younger students, who may only have an inkling that they’re interested in this stuff, and really show them what the potentials are, and empower them and give them some of the tools to be successful in research.”

The program has two goals for the students: to build an understanding of how physics problems emerge from thinking about biological systems like developing embryos, communicating bacteria, interacting animals and more, while also learning how ideas and methods from physics, modeling, data analysis and imaging connect to diverse biological phenomena.

Each year, the school has welcomed 24 students. The biggest cohort has come from the CUNY schools — eight students the first summer and five this year. The 2019 program also welcomed two students from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (better known as ETH Zurich), while the student farthest from home was Arunn Suntharalingam of Malaysia.

“My school doesn’t offer too many biophysics programs, so I thought this would be a good opportunity to get some insight into the field that I really want to work in,” said Colin Yancey, a physics major at the University of Maryland-College Park.

“We had a lot of biology and physics courses, but the research there is really separated between disciplines,” said Ella Muller of ETH Zurich. “I’m interested in the physics underlying living systems.”

“Here, we get a broad overview because Princeton has faculty from so many areas of biophysics,” said her classmate Kathrin Laxhuber.

Jiatian “Crystal” Wu from Emory and Nathan Khabyeh-Hasbani from CUNY-Baruch College are observing how white light separates into a rainbow — revealing white light’s many constituent wavelengths — when passed through a grating.

On weekdays, students attended a mix of sessions, including classroom-style lectures, problem sets where they worked alone and in groups, traditional research talks, and hands-on lab sessions.

During one lab, where the students recorded videos of swimming bacteria, physics major Mia Morrell from Emory University said: “I thought this was a good opportunity to learn some biology, but it’s a little intimidating. But we’re having a good time!”

The students also had a few “State of the Field” (SOTF) days that focused on a single broad topic in biophysics, featuring interlocking lectures from multiple faculty members tackling similar problems from different perspectives, to give the students a sense of how researchers combine theory and experiments in physics and biology to answer fundamental questions. An SOTF day might cover the neurobiology of animal behavior, communication in bacterial populations, or genetic networks in development.

Chemistry lecturer Jennifer Gadd (right) discusses with Wang, Vidal and Al Bassri how to verify the location of the first minimum of an Airy pattern.

The visiting undergraduates also got to explore Princeton and the surrounding areas, both to strengthen bonds between the students and to provide additional professional development. In the first week, students toured the different experimental labs and participated in demonstrations of the different kinds of measurements being made. On the last day, a panel discussion with two graduate students, two postdocs and two faculty gave the students a chance to ask about graduate school, career opportunities and research.

They also socialized together, with an afternoon of canoeing, a trip to Philadelphia, and barbeque dinners on the first and last evenings. Faculty members often ate lunch with the students in the dining hall, which students reported gave them valuable opportunities to build personal connections.

“Our goals for the center — including the summer school — are ambitious,” said Bialek. “If we succeed in all of our hopes, then we’re talking about redrawing the intellectual landscape in the border regions between physics and biology. We realize that as excited as we are about what we can do right now, that redrawing is a multigenerational activity. As with so many things in academia, this is enlightened self-interest. If we inspire more bright undergraduates to go into the field, it will be better for us. And we’ll know that things have changed because 20 years from now, people will speak differently about this part of the natural world.”

The Center for the Physics of Biological Function (CPBF), a joint effort between The Graduate Center at CUNY and Princeton University, is one of eleven Physics Frontier Centers established by the Physics Division of the National Science Foundation Directorate for Mathematical and Physical Sciences.