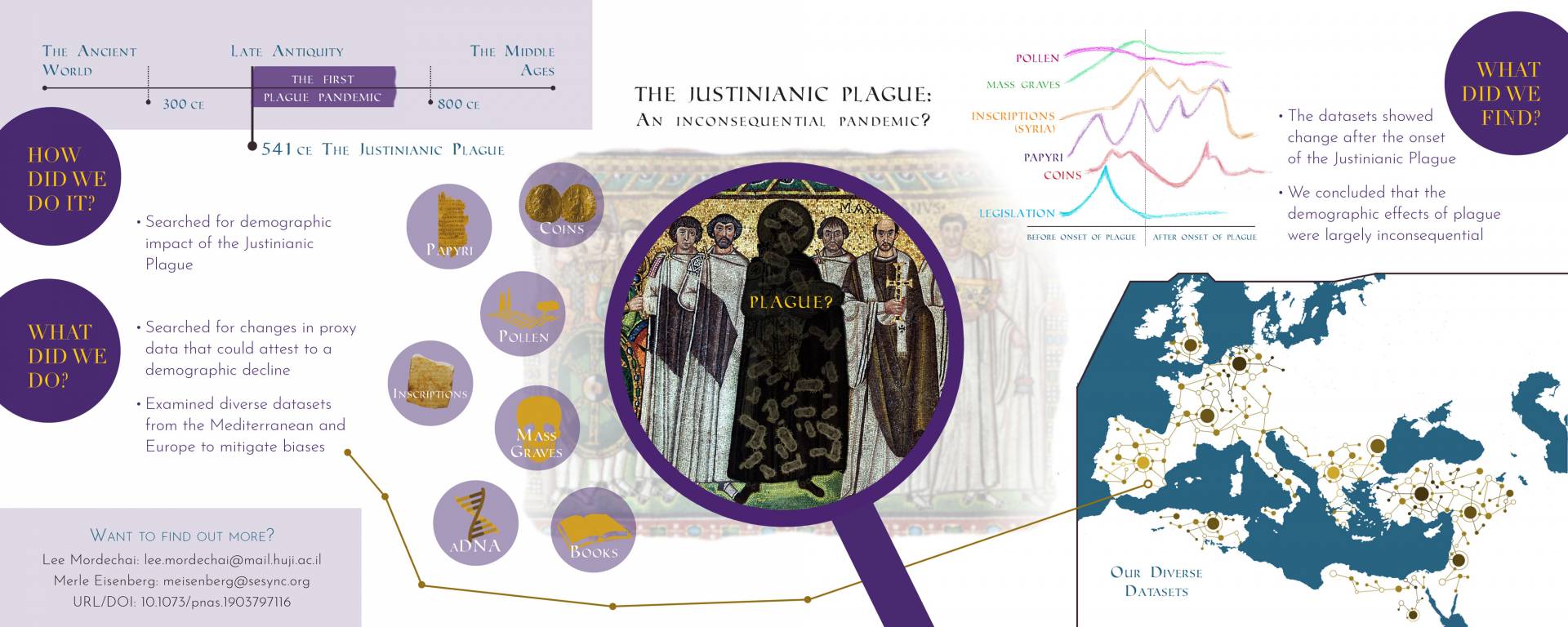

Researchers now have a clearer picture of the impact of the first plague pandemic, the Justinianic Plague, which lasted from about 541 to 750 CE.

The international team of scholars found that the rumors of the plague’s effects may have been greatly exaggerated. Led by researchers at Princeton's Climate Change and History Research Initiative (CCHRI) and the University of Maryland's National-Socio Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC), the team examined diverse datasets from a wide range of fields but found no concrete effects of the plague. Their paper appears in today's issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

“Our article is the first time such a large body of novel interdisciplinary evidence has been investigated in this context,” said lead author Lee Mordechai, co-lead of CCHRI and a 2017 Ph.D. graduate of Princeton’s Department of History. “If this plague was a key moment in human history that killed between a third and half the population of the Mediterranean world in just a few years, as is often claimed, we should have evidence for it, but our survey of datasets found none.”

Researchers from Princeton’s Climate Change and History Research Initiative investigated pollen counts, coinage and burial practices, and many other data sets to study the first plague. They concluded that the first major plague of late antiquity, also known as the Justinianic Plague, may have had its effects overestimated. The map in the lower right is a “nodal map” to represent their data collection across the region. For example, the researchers looked at hundreds of inscriptions from "Syria" (which at that time included modern Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Israel), so there is a node there with connections to other parts of the region. Similarly, a source written in central France mentioned sites in France and Italy.

The research team examined contemporary written sources, inscriptions, coinage, papyrus documents, pollen samples, plague genomes and mortuary archaeology. They focused on the period known as Late Antiquity (300-800 CE) that included major events such as the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the rise of Islam — events that have been sometimes attributed to plague, including in history textbooks.

“Our paper rewrites the history of Late Antiquity from an environmental perspective that doesn’t assume plague was responsible for changing the world,” said co-author Merle Eisenberg, a 2018 Ph.D. alumnus and a member of the CCHRI. “The paper is notable because historians led this PNAS publication, and we asked historical questions that focused on the potential social and economic effects of plague.”

The team found that previous scholars have focused on the most evocative written accounts, applying them to other places in the Mediterranean world while ignoring hundreds of contemporary texts that do not mention plague.

This early 7th century gravestone from Spain contains one of the only two inscriptions that explicitly refer to the Justinianic Plague.

“While plague studies is an interdisciplinary, demanding field of study, most plague scholars rely solely on the types of evidence they are trained to use. We are the first team to look for the impacts of the first plague pandemic in very diverse datasets. We found no reason to argue that the plague killed tens of millions of people as many have claimed,” said co-author Timothy Newfield, another co-lead of the CCHRI who is now an assistant professor of history and biology at Georgetown University. “Plague is often construed as shifting the course of history. It’s an easy explanation, too easy. It’s essential to establish a causal connection.”

Many of these datasets, such as agricultural production, show that trends that began before the plague outbreak continued without change.

“We used pollen evidence to estimate agricultural production, which shows no decrease associable with plague mortality. If there were fewer people working the land, this should have shown up in pollen, but it has failed to so far,” said co-author Adam Izdebski, a member of CCHRI, a research group leader at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and an assistant professor of history at Jagiellonian University.

Even some of the most well-known effects of large epidemics, such as changes in burial traditions, follow existing trends that began centuries earlier.

“We investigated a large dataset of human burials from before and after the plague outbreak, and the plague did not result in a significant change whether people buried the dead alone or with many others,” said co-author Janet Kay, a lecturer in the Humanities Council and history and the CSLA-Cotsen Postdoctoral Fellow in Late Antiquity in the Society of Fellows at Princeton. She contrasted that with the Black Death, a plague that took place about 800 years after the Justinianic Plague. “The Black Death killed vast numbers of people and did change how people disposed of corpses,” she said.

This mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, shows Emperor Justinian (who reigned from 527 to 565 C.E.) and members of his court. One influential late antique author claimed that Emperor Justinian was an “evil demon” who killed a trillion people during his reign, in various natural disasters. Another author asserted that the plague killed 99.9% of the population. The CCHRI researchers caution that these narratives need to be read in light of their historic contexts, not taken literally.

The researchers also used available plague genomes to trace the origin and evolution of the plague strains responsible for outbreak. That there was a plague that killed people across Eurasia is not in doubt, say the researchers. The question is just how many people.

Co-author Hendrik Poinar, a professor of evolution biology and director of the Ancient DNA Centre at McMaster University, added: “Although tracing the origins and development of the plague bacterium is crucial, the presence of the pathogen does not in itself mean catastrophe.”

“The Justinianic Plague: An inconsequential pandemic?” by Lee Mordechai, Merle Eisenberg, Timothy P. Newfield, Adam Izdebski, Janet Kay and Hendrik Poinari appears in the Dec. 2 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1903797116). The study is based upon work funded by the National Science Foundation DBI-1639145, Princeton University’s Climate Change and History Research Initiative, Georgetown University’s Environmental Initiative, the Max Planck Society, Poland's Ministry of Science and Higher Education, and the ACLS/Mellon Dissertation Fellowship.