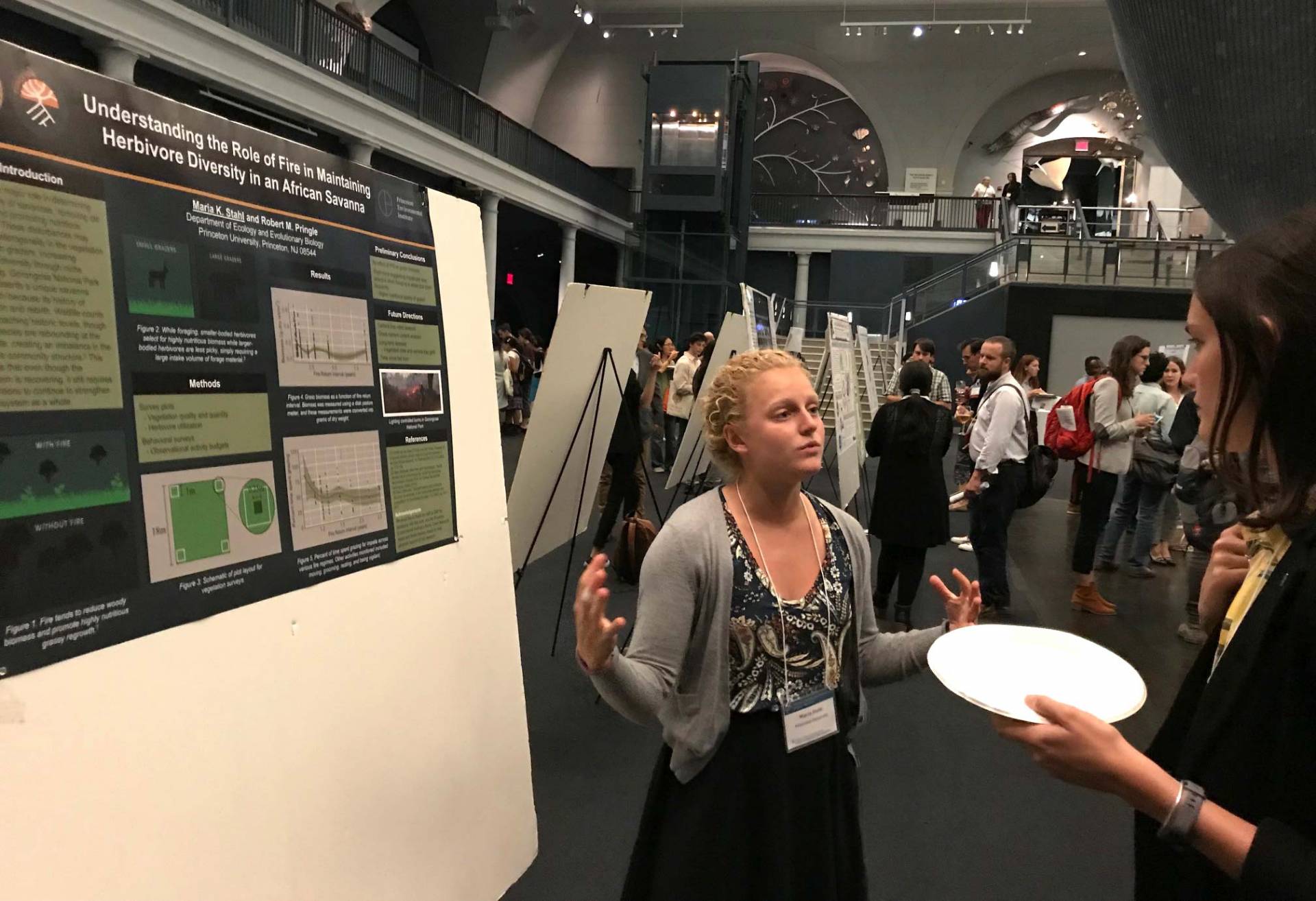

For her senior thesis, Maria Stahl of the Class of 2020 (at left, pictured in 2019 with PEI summer intern Zoe Rennie, Class of 2021) studied whether herbivores’ grazing behavior was influenced by how often tracts of land had been burned. Stahl conducted vegetation surveys at 12 sites in Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park that had burned at least once in the past 18 years, assessing the amount of woody biomass (trees and shrubs), grass both old and new, and bare earth.

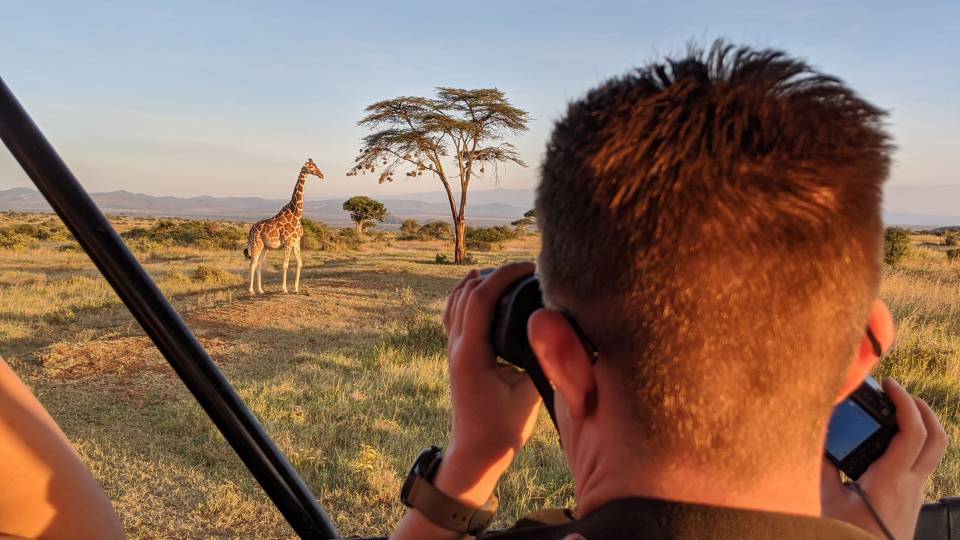

Fire climbed into the sky on either side of the narrow dirt road as Maria Stahl — then a Princeton Environmental Institute intern in the research group of Robert Pringle, an associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology — returned to camp one day in 2017. She had spent a long, hot afternoon on the sweeping treeless floodplain of Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park observing animal grazing behavior and collecting fecal samples for a project on the effect of large herbivores on vegetation growth.

Maria Stahl

“The sky above the flames was littered not only with ash, but also with huge flutters of butterflies and clouds of grasshoppers escaping the blaze,” she described in her senior thesis. “Every now and then a stray oribi or kudu darted out from the grassland to cross the road to safety.”

Stahl, who graduated from Princeton this year with a degree in ecology and evolutionary biology, recounted: “We were driving through a controlled burn and it was unsettling to be so close. Our faces were covered with soot afterward.”

The sight of the flames inspired Stahl to study one of the most controversial and poorly understood topics in conservation — fire. Specifically, Stahl wanted to know how controlled burns by Gorongosa park officials affect the grazing behavior of herbivores such as elephant and wildebeest in an ecosystem recovering from being nearly wiped out by the 15-year Mozambican civil war that ended in 1992.

“That experience got me thinking about the broader impacts of the fires set at Gorongosa, especially on an ecosystem that has not yet reached a stable state,” said Stahl, whose thesis research was supported by a Becky Colvin Memorial Award from PEI and the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, as well as through a PEI Environmental Scholar award.

“I wanted to design a project that would help the park know how fires are impacting plants and animals,” Stahl said. “I’m hoping that even if this project doesn’t have immediate implications for Gorongosa, that other people will continue researching fire regimes there now that I’ve brought attention to it. I really see this project as a jumping-off point for someone looking at controlled burns and their ecological impact.”

Stahl was inspired by the sight of a controlled burn at Gorongosa National Park to study one of the most controversial and poorly understood topics in conservation — fire. Her work could help park management decide how often and how much land to burn at a given time.

From the pine forests of New Jersey to African savannas, fire replenishes certain ecosystems by burning off dead biomass, fertilizing soil and making space for new growth. But as people have occupied these habitats, fire has come to be regarded as a scourge to life and property.

Wildland fires tend to conjure ideas of the conflagrations that engulfed Australia in 2019 and 2020, Stahl said. “The fires in Australia were so destructive because they burned for months,” she said. “A fire that burns for a few days or a week can be really good for an ecosystem.”

“A lot of people think that fires are a bad thing, but they’re an ancient thing that have been part of many landscapes for a long time,” said Pringle, Stahl’s senior thesis adviser and a PEI associated faculty member. “Many African savannas are maintained by fires. In a recovering savanna ecosystem like Gorongosa, it’s critically important to find a good balance when it comes to fire.”

Stahl wanted to know how controlled burns at Gorongosa affect the grazing behavior of 16 animal species (pictured, waterbuck). Fourteen were ruminants that, like cows, periodically regurgitate partially digested food that they chew and swallow again, and prefer thin-membraned, high-protein plants such as grass. The other two, elephants and warthogs, were hindgut fermenters that tend to have a more varied diet that includes woody plants.

With her work, Stahl aimed to provide guidelines for park management as to how often and how much land to burn at a given time. She focused on whether the grazing behavior of the park’s recovering herbivores was influenced by how often tracts of land had been burned. Stahl selected 12 sites within the park that had burned as often as once per year to only once in the past 18 years. She conducted vegetation surveys of subplots at each site (48 total), assessing the amount of woody biomass (trees and shrubs), grass both old and new, and bare earth.

Stahl then focused on 16 animal species: buffalo, bushbuck, common duiker, red duiker, eland, elephant, hartebeest, impala, kudu, nyala, oribi, reedbuck, sable antelope, warthog, waterbuck and wildebeest. Fourteen of the species are ruminants, which means that, like cows, they periodically regurgitate partially digested food that they chew and swallow again. These animals’ digestive systems extract the highest amount of plant protein, but takes longer, so they prefer thin-membraned, high-protein plants such as grass.

On the other hand, elephants and warthogs are hindgut fermenters with fast-moving systems that extract proteins less efficiently. Hindgut fermenters tend to have a more varied diet that includes woody plants.

Using motion-activated cameras, Stahl captured the animals that visited each of the 12 sites and noted how long they stayed to feed. She also tabulated the amount of dung in each plot to help gauge how often herbivores were in the area.

Stahl found that body size and gut type did appear to influence the degree to which herbivores select for the quality and quantity of their food. The animals she studied tended to stay away from very recently burned areas, likely due to the lack of forage material available, she said.

However, body size and digestive strategy did influence when animals eventually returned to burned areas. Large ungulates — or animals with hooves — such as wildebeests and buffalo, as well as the ruminants, were much slower to return to burned areas. Hindgut fermenters such as elephants and small ungulates such duikers and oribis resumed grazing on burned land much sooner.

Stahl’s research provides a reference point for understanding the role of fire at Gorongosa, Pringle said. Previous research from his group had found that in the decades when Gorongosa's herbivore populations were low the amount of tree cover increased dramatically.

“Fire may have an important role to play in opening the habitat back up so that the grass-eating herbivores can recover,” Pringle said. “What Maria has done is a valuable step toward identifying a controlled-burning regime that facilitates the recovery of the whole ecosystem in a scientifically accurate way.”

As a researcher, Stahl stood out for her determination to spend hours in the field designing and fine-tuning experiments she came up with herself, Pringle said. “Especially for our students who might be oriented toward a career in science, you want to let them build their own idea and implement it,” Pringle said. “That is such an essence of science and it’s not something that comes naturally — it’s a skill that’s acquired.

“When I’m thinking about the value of a Princeton senior thesis, it’s partly about the final product but mostly about the learning process,” he continued. “Maria produced a beautiful piece of work and it reflects the learning process of a young scientist.”

Stahl (presenting her research at the Student Conference on Conservation Science at the American Museum of Natural History in October 2019) found that the animals she studied tended to stay away from very recently burned areas, likely due to the lack of forage material. But body size and gut type influenced when animals eventually returned. Small-hoofed animals and animals such as elephants with more varied diets resumed grazing on burned land much sooner.

For Stahl, one of the most valuable outcomes of her research was the opportunity to work in a wild habitat independently pursuing her own research. After graduation, Stahl will work at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory with ecology and evolutionary biology graduate student Ian Miller on his study — funded by a PEI Walbridge Fund Graduate Award — on the effect of climate change on the spread of plant pathogens.

“If I’ve learned anything from Rob, it’s that being curious is always helpful,” Stahl said.

“This was my project, which a lot of students might not be able to say,” she said. “I did a PEI internship with Rob after my first year at Princeton and I haven’t looked back. I was blown away by how interesting and fun working in the field can be. Those experiences have been the most formative of my Princeton career.”