Christopher Griffin, assistant professor of geosciences at Princeton, poses with a T. rex skull from the Princeton natural history collection.

For decades, paleontologists have debated whether a small tyrannosauroid skull found in 1942 belonged to a juvenile T. rex or was a full-grown member of a previously unknown species, eventually dubbed Nanotyrannus lancensis.

A recent study in the journal Science, led by a collaboration between Princeton University and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History (CMNH), answers the question: Yes, Nanotyrannus is its own species, and this small skull represents a full-grown adult.

Prior to this study, the scientific community had come to a strong consensus that the specimen was juvenile T. rex, said Christopher Griffin, an assistant professor of geosciences at Princeton and the lead scientist on the project.

But then Caitlin Colleary, the CMNH vertebrate paleontology curator responsible for the skull, saw a way to use Griffin’s expertise in age-dating dinosaur bones to settle the question.

“As a curator, I often have to find a balance between conservation and discovery,” said Colleary. “If our only objective was conservation, we would keep a lot of amazing fossils locked in cabinets, but we collect them to learn about the past, about ancient creatures.”

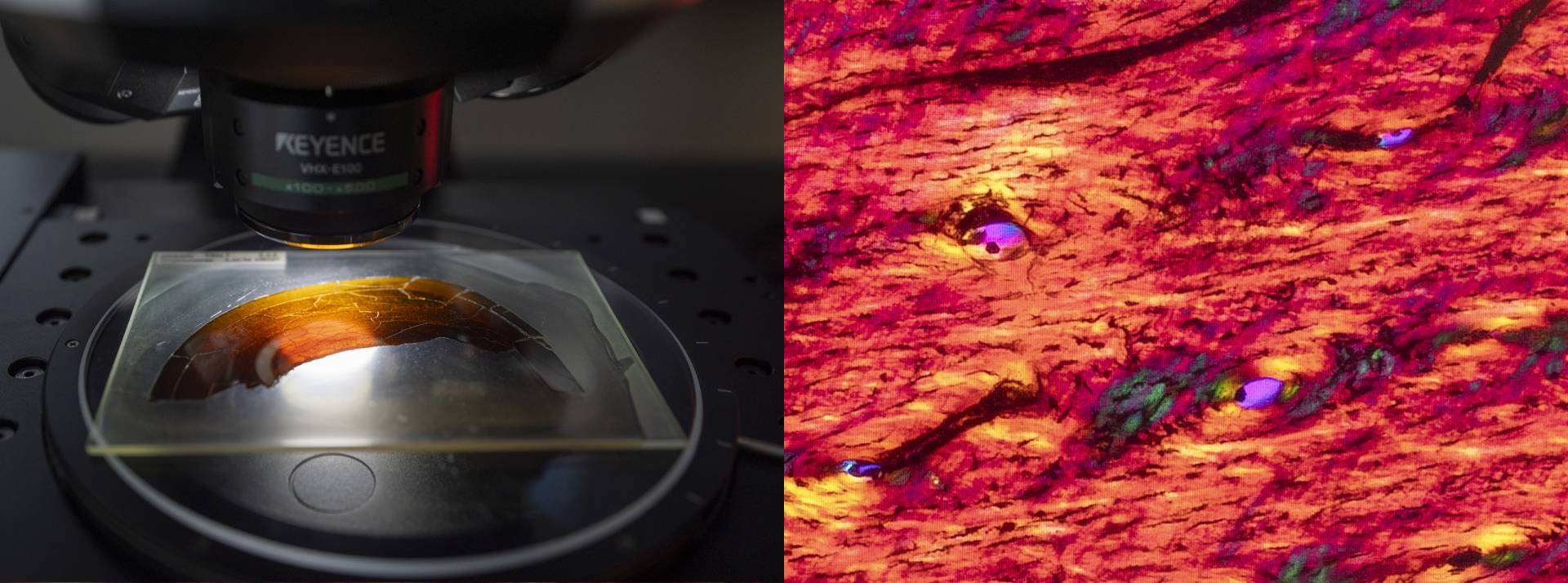

This microscopic cross-section through a Nanotyrannus hyoid shows age rings clustered on the right edge, evidence that this animal was fully grown, even though it is less than half the size of a full-grown Tyrannosaurus rex.

Growth rings on a dinosaur bone

Griffin is infamous among paleontologists for cutting into dinosaur bones to look at their growth rings. Like tree rings that grow each year and reveal the tree’s age, dinosaur long bones show annual growth rings.

Skulls don’t, because they remodel and change as they grow, leaving a muddled age record. But Colleary knew that the Cleveland museum’s skull included small, straight bones that are technically part of a skull — the hyoid.

In humans, hyoid bones are horseshoe-shaped and located at the front of the throat. Dinosaurs and their modern relatives have two separate hyoids: short, straight bones running beneath the jaw to support the tongue.

“This isn’t a new technique, but up until now, age dating has been exclusively used on limb bones and ribs,” Griffin said. “The novelty of this study is showing that these slender throat bones preserve a record of growth like limbs and ribs do.”

No one had thought to look for growth rings in a hyoid before, because “why would you even bother to look, if you have a femur or a rib bone?” Colleary said.

Complicating matters, the skull is what’s known as a holotype — the first-described and definitive example of a new species. And Griffin was going to cut into it.

“Historically, a lot of curators probably wouldn’t have approved a destructive analysis like this on a holotype,” Colleary said. “But because I do molecular research, I know the value of hidden information inside a fossil. This is a perfect example of using destructive analyses appropriately, because we gained so much more information than we lost.”

This slice through the hyoid of a full-grown ostrich helped Griffin illustrate growth patterns in modern-day dinosaurs (birds).

Eureka! … oof

Before he dared cut into the Nanotyrannus holotype, Griffin investigated hyoids of modern dinosaurs — better known as birds — and dinosaur cousins like crocodiles, alligators and caimans.

He found that, just like long bones, hyoids show widely spaced growth rings for juveniles and tightly clustered rings at the bone edges for adults. This is such a well-known pattern in long bones that those bunched-together adult growth rings have their own name: EFS, for “external fundamental system.”

Once he had documented that the delicate hyoid, under sufficient magnification, does in fact reveal the same pattern as a femur or rib, Griffin was ready to cut into the Nanotyrannus hyoid.

Colleary and Griffin both expected to find confirmation that the skull belonged to a juvenile T. rex. But when Griffin slid the wafer-thin slice of hyoid under his microscope, he was shocked.

“I saw what, for all the world, looked like EFS, the external fundamental system,” Griffin said. “An EFS is unambiguous. You see it, and boom, you know this thing’s full-grown. My first thought was, ‘Oof, this is going to be a lot more work.’”

To challenge the accepted theory that the skull belonged to a juvenile T. rex, “we had to definitively show that this hyoid technique works,” Griffin said. “Maybe crocs and ostriches aren’t the best models? We had to document it in other theropod dinosaurs, other medium-sized dinosaurs, other large-bodied animals, even other tyrannosaurs.”

It took years to build up a convincing database of hyoid and long-bone measurements. Even finding hyoids in museum collections was tricky, because the tiny bones aren’t catalogued separately from skulls. And then Griffin needed permission to cut slices, grind them to the perfect dimensions, and slide them under his microscope — after thoroughly imaging, molding and documenting the untouched original, of course.

Just how small was Nanotyrannus?

This artist's rendering shows a full-grown Nanotyrannus (left) running with a juvenile T. rex (right front) and a full-sized T. rex (right rear).

Despite the name, Nanotyrannus was a medium-sized dinosaur, with adults standing about six feet tall at the hip. The holotype skull is just under 2 feet long (22 inches, or 57 cm), while adult T. rex skulls are typically 4 to 6 feet (1 to 2 m).

“It’s still a big animal, it’s just that Tyrannosaurus rex is so big that by comparison, Nanotyrannus seems really, really small — about a tenth of the size by total body mass,” Griffin said.

Confirming the existence of this second predatory species is leading paleontologists to rethink the ecosystem just before the catastrophic end of the dinosaur era, Colleary said.

Griffin added, “Before, we thought there was only one major predator at the end of the Cretaceous in western North America, but now we know there was more diversity, more ecological complexity leading up to the mass extinction.”

Sharing the science

Griffin completed and published his hyoid and long-bone database using a new digital microscope funded by the Princeton endowment.

“This fancy microscope takes enormous, high-resolution, whole-slide images,” said Griffin. “We posted every single piece of data that we have on an online repository that goes with this paper. In fact, I don’t even have an eyepiece to look through, it just digitally captures the whole field. So whoever downloads these big files is seeing exactly what I see when the slide is on my microscope.”

While Griffin and his coauthors were working, a separate research team in North Carolina studied a complete skeleton that they identified as Nanotyrannus lancensis by comparison with the CMNH holotype skull. “They have an amazing specimen,” Griffin said. “100% complete, down to the tip of the tail.” Their paper was published in Nature a month before Griffin’s Science paper and also concluded that Nanotyrannus was a separate predatory species that lived concurrently with T. rex.

The two studies reinforce each other’s conclusions and should settle the question for good, Colleary said. “It’s great to confirm that our Nanotyrannus was fully grown. It’s also really exciting to have also contributed a new tool — hyoid age dating — to the field of vertebrate paleontology,” she said. “Museum collections have such an important role to play in making these types of discoveries. We’ve invested in the care of this specimen for more than 80 years, and that’s what enables studies like this to happen.”

“A diminutive tyrannosaur lived alongside Tyrannosaurus rex” by Christopher T. Griffin, Jeb Bugos, Ashley W. Poust, Zachary S. Morris, Riley S. Sombathy, Michael D. D’Emic, Patrick M. O’Connor, Holger Petermann, Matteo Fabbri, and Caitlin Colleary, appears in the Dec. 4 issue of Science (DOI: 10.1126/science.adx8706). The research was supported by the Princeton University and Yale University endowments, as well as the National Science Foundation (NSF Postdoctoral Research Fellowship in Biology Award 2010677 to CTG).

Griffin took 30-micron-thick slices through bones of birds, crocodilians, tyrannosauroids, allosaurs, and other living and extinct organisms to show that the hyoids can reveal a creature's age.