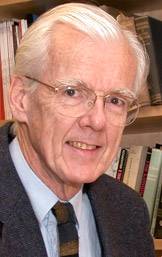

Bart Hoebel, a Princeton professor of psychology and the Princeton Neuroscience Institute who became internationally known for his research on food addiction, died of cancer Saturday, June 11, in Princeton. He was 76.

A member of the Princeton faculty since 1963, Hoebel's interest in understanding how the brain rewards behavior encompassed a breadth of research and led to discoveries in the areas of eating disorders and obesity, addiction, alcohol consumption and depression. He pioneered studies into the mental rewards of eating, and his research on sugar addiction in rats generated worldwide attention for its possible public health applications.

"His studies on food addiction led to the development of a new subfield and a novel approach to studying the obesity epidemic," said Nicole Avena, a visiting assistant professor of psychology at Princeton and a research assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Florida.

"The work Bart produced has been influential on many other scientists," added Avena, who earned her Ph.D. in psychology and neuroscience from Princeton in 2006 under Hoebel's mentorship and continued to collaborate with him through 2010. "He aimed to understand brain mechanisms that drive us to engage in certain types of behavior, like eating, and those findings really laid the groundwork for future research."

Deborah Prentice, the Alexander Stewart 1886 Professor of Psychology and chair of the Department of Psychology at Princeton, said Hoebel equally influenced scientists and students.

"His research is important, of course, but what impressed me most about Bart was his dedication to students," Prentice said. "He was a gifted mentor, with a real passion for training young scientists, and the work of his lab is ongoing even after his death -- just as he would have wanted."

In recent years, Hoebel's lab led research demonstrating that sugar can be an addictive substance, causing changes in the brains and behaviors of rats similar to many drugs of abuse, such as cocaine, morphine and nicotine. In 2008 Hoebel's lab completed an animal model of sugar dependency that was the first set of comprehensive studies showing a strong suggestion of sugar addiction in rats and a brain mechanism that might underlie it.

Hoebel's work allowed scientists to examine more deeply the connections between food cravings and brain physiology, with the hope that the research could one day influence work related to humans with eating disorders.

"Bart was definitely a pioneer. He was not afraid to put out a new idea that people may not necessarily agree with at first and run with it. Our first work with food addiction in rats was really spurred by Bart's enthusiasm," Avena said.

Hoebel had been interested in the brain mechanisms that control appetite and body weight since he was an undergraduate at Harvard University studying with the renowned behaviorist B.F. Skinner.

Most recently in 2010, Hoebel's research team studied the differences between high-fructose corn syrup and table sugar in effecting weight gain in rats and in affecting circulating blood fats called triglycerides. In earlier work in 2004, he had shown that the desires for fatty foods and alcohol share a chemical trigger in the brain, helping to explain one of the mechanisms involved in alcohol dependence and adding to scientists' understanding of the neurological link between the desires for alcohol and food.

"Bart always loved to contribute. His science on diet and food disorders seemed to be motivated mainly by an enthusiasm for helping people," said Michael Graziano, an associate professor of psychology and the Princeton Neuroscience Institute who first met Hoebel while an undergraduate psychology student.

Sarah Leibowitz, a longtime collaborator of Hoebel's and an associate professor at Rockefeller University, said Hoebel was a leader in studying the neural basis for feeding and reward. Some of his earlier research included examinations of how animals regulate their body weight and the neural pathways and neurochemicals involved with motivation. A 1999 study involved examining the brain chemistry of motivation and depression, looking at how the chemical dopamine reinforces connections between cognitive inputs and behavioral output, so that successful behaviors are repeated.

"Bart was very creative and always tried to come up with original ideas. He wanted to come out with something that paved the way for new areas of research," said Leibowitz, who is editing an upcoming issue of the journal Physiology & Behavior in which various scientists have written about Hoebel's influence on their work.

Beyond his research, Hoebel was a gracious mentor to colleagues and students, his peers said.

"He loved teaching and was dedicated to teaching undergraduates -- not just getting up there and lecturing in class, but training young people to be scientists and really caring about the outcomes of their lives," said Barry Jacobs, professor of psychology and the Princeton Neuroscience Institute.

Mark Gold, chair of the department of psychiatry at the University of Florida and a collaborator with Hoebel on food addiction research, said: "Bart was the very best example of a friend, professor and mentor. He was always the most generous with his time, ideas and support. He helped many of his students achieve great things but also to find a balance in their lives."

Outside of the lab, Hoebel was described by colleagues as a "renaissance man" whose generosity and sense of adventure included hobbies such as hot air ballooning, Christmas tree farming and building a steam calliope into an antique fire truck to drive in parades. He also ran a nonprofit organization, the Delaware River Steamboat Floating Classroom, where students and groups experience interactive ecology lessons on board a replica of an 1880 sternwheeler on the Delaware River.

"Bart was so full of life and enthusiasm, and definitely the most interesting person I have ever met," Avena said.

Hoebel was born May 29, 1935, in New York City. He earned his undergraduate degree in psychology from Harvard in 1957 and his Ph.D. in 1962 in physiological psychology from the University of Pennsylvania, where he also worked as a postdoctoral fellow and instructor before joining the Princeton faculty.

Hoebel is survived by his daughters, Valerie Hoebel and Cary Hoebel Lane; a son, Brett; a son-in-law, Ken Lane; and two grandchildren, Fanter and Finn Lane. He was pre-deceased by his wife, Cindy.

A private family gathering for Hoebel was held earlier this week, and the Department of Psychology held a living memorial service for him in January. In lieu of flowers, donations in Hoebel's honor may be sent to the Delaware Steamboat Floating Classroom via its website www.steamboatclassroom.org, or to the Sierra Club via its website www.sierraclub.org.