When Dickinson College rising senior Rizwan Saffie returns to his housing in Princeton's Spelman Halls after a day's work in the lab, he knows that science doesn't have to be over yet: he has friends with whom he can discuss experiments and findings.

"It's nice being in a community of science," Saffie said. "We all talk about science, just randomly hanging out."

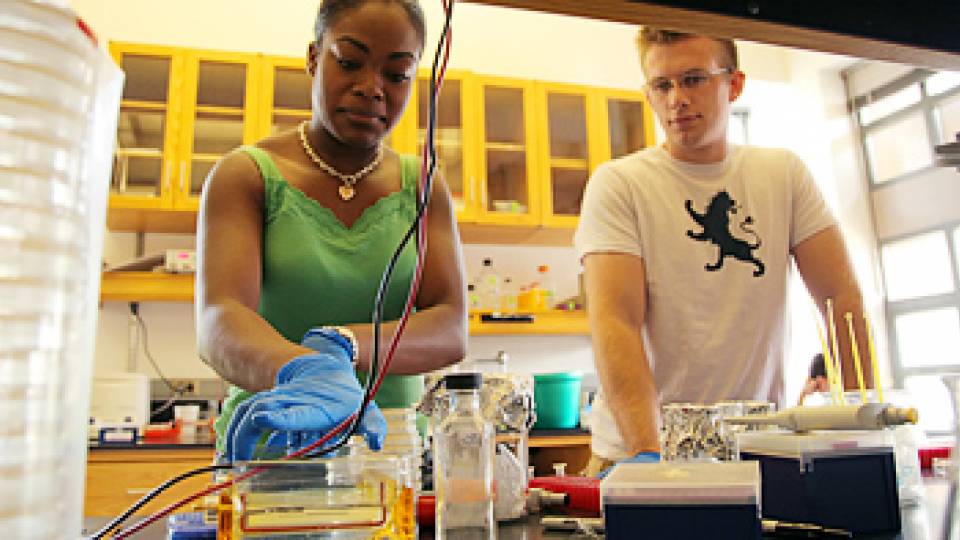

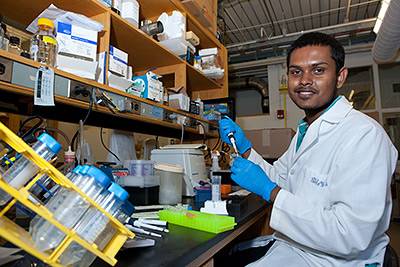

Rizwan Saffie, a rising senior at Dickinson College, has spent 10 weeks learning about how certain enzymes affect the spread of breast cancer to the lungs. He said he has enjoyed talking about science not only in the lab of Yibin Kang, the Warner-Lambert/Parke-Davis Professor of Molecular Biology, but also in his campus residence.

A tight-knit community is one of many things that the 72 college students in Princeton University's Summer Undergraduate Research Program in Molecular and Quantitative and Computational Biology enjoy as they immerse themselves in scientific research over 10 weeks.

The students, selected from a nationwide pool, carry out their own project within a research group, attending lab group meetings and collaborating with faculty, postdoctoral fellows, graduate students and other undergraduates just as they would if they were already professional scientists. They also interact with peers and mentors through research discussion groups and career forums. At the end of the summer, the students present their work in a poster session to established researchers.

"It mimics the true scientific community," said Saffie, a biochemistry and molecular biology major. He is examining how certain enzymes affect the spread of breast cancer to the lungs in the lab of Yibin Kang, the Warner-Lambert/Parke-Davis Professor of Molecular Biology. A crucial factor in Saffie's enjoyment of the unfamiliar terrain of lab work has been the friendly, casual atmosphere encouraged by his labmates, he said.

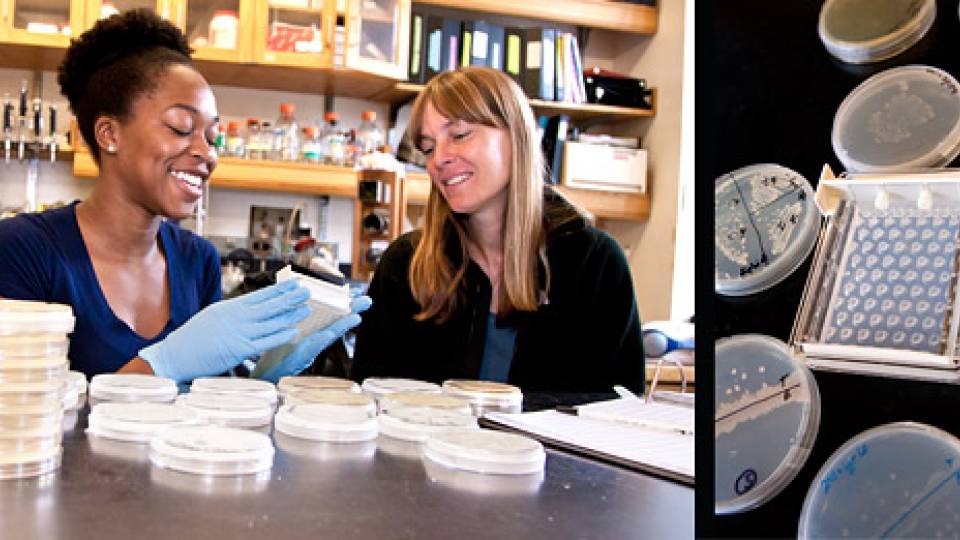

Swarthmore College rising junior Jessie Bacha agreed, citing one of the highlights of her week as lunches with fellow researchers. "I wasn't expecting it to be as relaxed as it's been," she said. "I've had fun getting to talk to lab members and hearing about their experiences, getting to be part of the lab community."

She said she also has appreciated being mentored by Patrick Gibney, a postdoctoral research associate in the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics. "Pat has been very helpful and supportive throughout the program and I feel lucky to have such a great mentor," Bacha said.

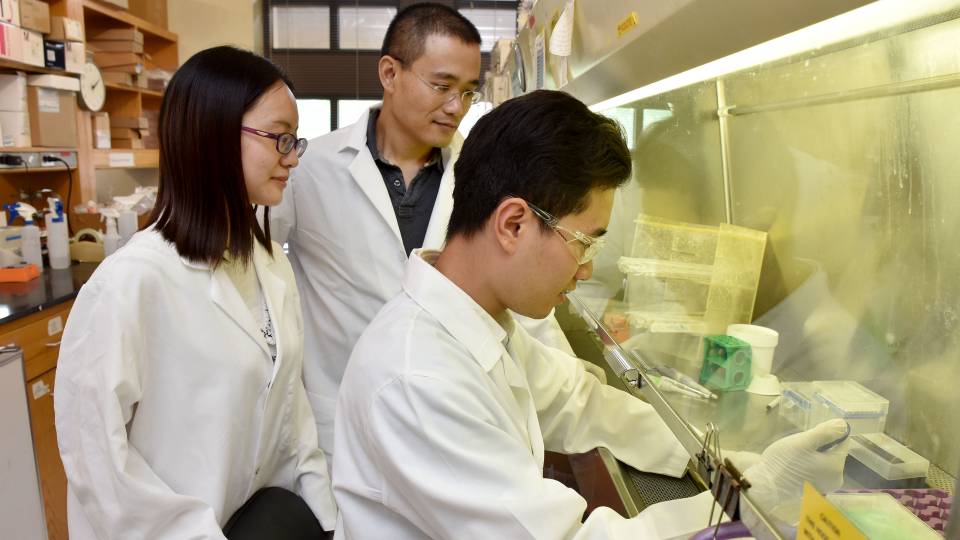

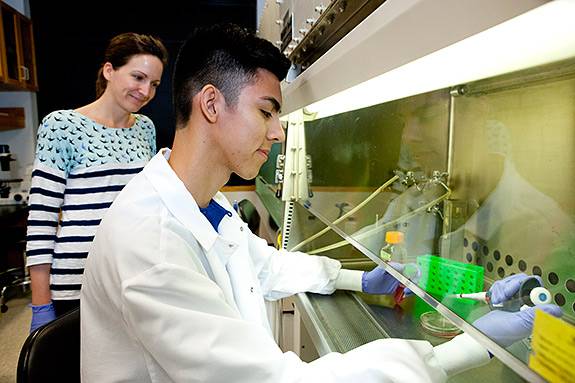

Irving Miramontes (right), a rising junior at the University of Texas-El Paso, has spent the summer conducting research on how specific proteins provide a "sense of direction" to cells, based in the lab of Danelle Devenport (left), an assistant professor of molecular biology.

The program is supported by the Department of Molecular Biology, the Lewis-Sigler Institute, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Genentech Foundation and the New Jersey Commission on Cancer Research. The program gives participants a taste of the high and the low points of the scientific process. Bacha noted that a lesson that will stay with her is that scientists cannot always be as efficient and productive as they might like.

"Science doesn't go right or go on your terms all the time," said Bacha, a biology major who is working in the lab of David Botstein, the Anthony B. Evnin '62 Professor of Genomics. "But when it does go right, it's really rewarding. It takes time to get something to work or figure out how to get something to work," she said.

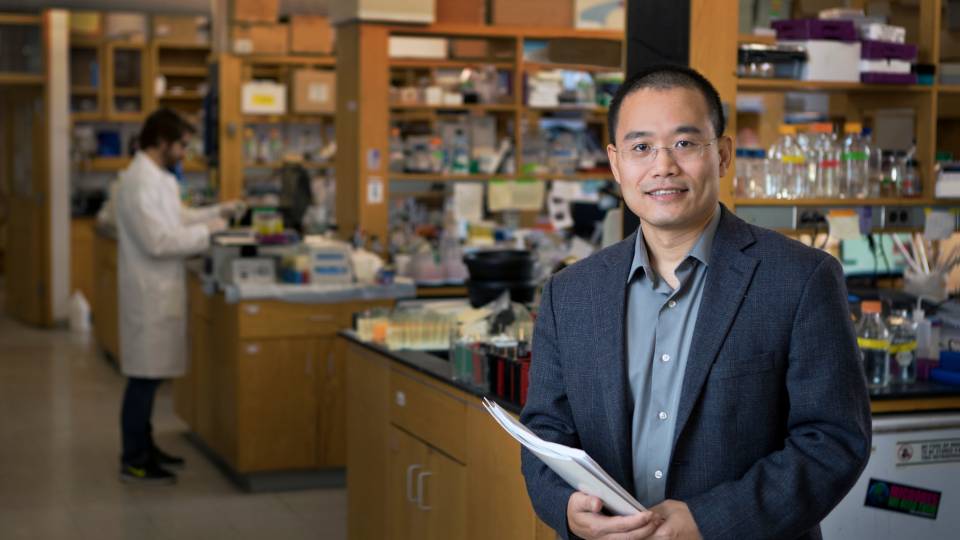

Kang observed how the students' contributions to lab morale are especially important.

"They bring energy," he said. "They are the kinds of students who stay late and work hard ... they have the passion to learn as much as they can." And sometimes, Kang added, they bring even more. "You don't expect them to make major discoveries in such a short time, but sometimes they do," he said.

Kang's sentiment is echoed by Danelle Devenport, an assistant professor of molecular biology and a mentor to Irving Miramontes, a rising junior at the University of Texas-El Paso who is majoring in cellular and molecular biochemistry. Miramontes is working to understand how specific proteins provide a "sense of direction" to cells, enabling such phenomena as a fixed-growth direction of animal hair. Because scientists know so little about how cells transmit that direction along to neighboring cells, anything that Miramontes might uncover could be "a huge contribution," Devenport said.

And it goes both ways: Devenport said she could already see how students such as Miramontes were benefiting from the training they are receiving from the program. "It doesn't matter what they are studying, it's the scientific thinking," she said.

The program succeeds in reinforcing students' interest in scientific careers: More than 70 percent of former participants have since pursued degrees in Ph.D., M.D. or combined M.D./Ph.D. programs, noted program director and molecular biology senior lecturer Alison Gammie.

Kang pointed out that the program also enables Princeton to recruit talented undergraduates for graduate study at the University — an important facet of his department's mission. As professors gain a favorable impression of the undergraduates under their watch, so, too, do the undergraduates begin to think about what it could be like to continue their studies at Princeton. "We recruit the best students," Kang said. "It's building this pipeline of recruiting talent from really great colleges."

For Saffie, the confidence he has gained working with complex laboratory techniques and grappling with challenging questions has left him feeling more prepared to pursue an advanced degree in science, wherever he ends up.

"When I first got here I wasn't sure if I was ready, but then after being exposed to the different techniques and told to do this [work] independently, I'm much more confident and educated in my own project," he said. "Now I think I'm ready for grad school."