On the verdant campus of University College Dublin, nearly 300 public health experts and practitioners, government officials, scholars and students gathered to discuss the lessons learned from the Ebola crisis as part of the third annual Princeton-Fung Global Forum.

The two-day conversation investigated global health crises, using the recent Ebola outbreak in West Africa as a case study of a "modern plague." Designed to examine public health disasters from an interdisciplinary perspective, the forum focused on history, science, politics, communications, economics and more to better understand the challenges associated with modern plagues.

"Recent viral outbreaks — Ebola, avian flu and the respiratory syndromes known as SARS and MERS — have presented the world with a formidable quandary," Princeton University President Christopher L. Eisgruber said during his introductory remarks Nov. 2. "Resolving these crises requires a multidisciplinary approach involving not only public health and medical knowledge but also an understanding of the economic, environmental, political and historical roots and consequences of these plagues. This conference will bring together all these perspectives in the hopes of identifying methods for avoiding future crises."

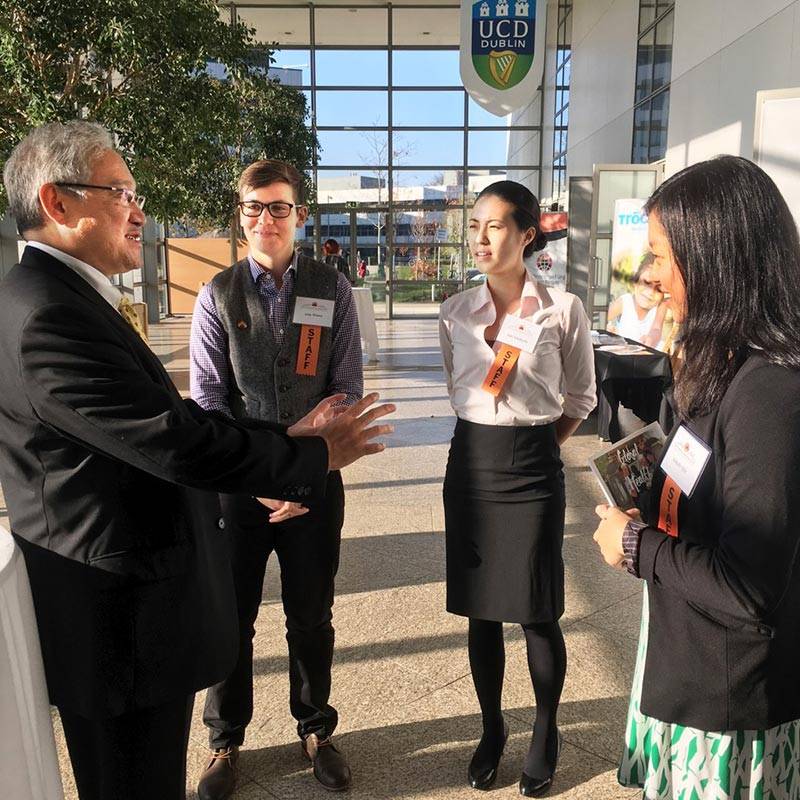

From right, Princeton senior Melody Qiu and graduate students Saki Takahashi and Amy Winter meet 1970 alumnus William Fung, whose gift established the conference in 2012. (Photo by Ryan Maguire, Office of Communications)

Speakers, moderators and attendees hailed from more than 20 countries, including several West African nations.

Fourteen Princeton faculty members from a range of disciplines served as panelists, joining other academics and representatives from relief agencies, government and nongovernmental organizations. Journalists from The New York Times, The Washington Post and NPR served as moderators. More than 40 Princeton alumni and students attended as participants.

William Fung, a 1970 Princeton alumnus and businessman whose generous $10 million gift created the Princeton-Fung Global Forum, introduced the issue with four important questions: Are plagues inevitable? What are the causes of modern plagues? How difficult is it to contain epidemics? And what are the social, political and economic impacts of plagues?

Fung's questions guided the two-day conversation at O'Reilly Hall, which began with a historical examination of plagues and concluded with policy solutions. While the six panels and four keynote addresses were wide-ranging, several themes emerged.

The discussion extended online, with the hashtag #FungForum trending in the United States on Twitter during the first morning of the forum.

A panel on "The Politics of Plague" featured, from left, João Biehl, the Susan Dod Brown Professor of Anthropology and co-director of the Program in Global Health and Health Policy at Princeton; Amaney Jamal, the Edwards S. Sanford Professor of Politics at Princeton; Dominic MacSorley, CEO of Concern Worldwide, a charity that works globally with the poor; Leonard Wantchekon, a professor of politics and international affairs at Princeton; and moderator Joel Achenbach, staff writer for The Washington Post and a 1982 Princeton alumnus. (Photo by Angela Halpin for Princeton University)

Responding to the next outbreak

One of the key takeaways woven throughout the two days was the need to be nimbler, acting quickly during times of crisis.

"The disease was neither expected nor suspected," Margaret Chan, director-general of the World Health Organization, said during her Nov. 2 address. "The virus circulated undetected off every radar screen for three months. The earliest cases in Liberia and Sierra Leone were likewise missed. This all gave the virus a momentous head start, and national and international responders could not begin to catch up until October. Late detection and delayed intervention contributed to the outbreak size."

Margaret Chan, the director-general of the World Health Organization, gave a keynote address focusing on the Ebola crisis and calling for universal health coverage. (Photo by Angela Halpin for Princeton University)

One solution to this quandary is the development of a global vaccine fund, as proposed by speakers Adel Mahmoud from Princeton and Jeremy Farrar from the Wellcome Trust. Supported by governments, foundations and pharmaceutical companies, this fund could carry promising vaccines from development to deployment.

For example, Ebola vaccine candidates were available well before the time of the outbreak, but no incentive existed for companies or governments to test them given the relatively small number of affected patients prior to this latest outbreak. Had one been tested and approved, public health workers could have vaccinated people from the start, saving thousands of lives.

"Next time, we need to do a better job. We need a global vaccine fund for this kind of infection," Peter Piot, co-discoverer of Ebola and professor at the London School of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene, said during the first keynote address. "We need funding for control. Without a stronger system, it will be very difficult to absorb shocks and prevent major outbreaks, or small outbreaks that become major. The Ebola crisis was a perfect storm of environmental and political factors, infrastructure issues and a failure to understand cultural traditions and beliefs. It was a total collapse of trust."

Piot's themes were echoed across all panels throughout the two-day event. In many panel discussions, particular focus was placed on the political hurdles involved with public health crises, both at the local and national level.

"There needs to be more interfacing with local government and international organizations," said panelist Amaney Jamal, the Edwards S. Sanford Professor of Politics at Princeton. "We see a power vacuum in Liberia. It wasn't clear how to get down to these local villages. It wasn't clear who was administering treatment or keeping things in control. In the future, we need some type of private and public partnership. You need to build local capacity for health care across the board."

On the local level, community health workers were especially vital during the Ebola crisis. Serving as cultural conduits, these frontline public health workers helped to identify and diagnose those infected by the virus. In many cases, these workers were not even paid.

"You can't build resilient health systems if you don't have health workers," said Mary Robinson, former president of Ireland, U.N. special envoy for climate change and founder of the Mary Robinson Foundation — Climate Justice, during her luncheon keynote address Nov. 2.

"We trained a massive amount of 'contact tracers,'" said Rebecca Levine, a 2001 Princeton alumna and officer with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "They were people actually from that village who would make it part of a neighborly visit."

During his Nov. 3 luncheon keynote address, Raj Panjabi, instructor in medicine at Harvard University Medical School and associate physician in the Division of Global Health Equity at Brigham and Women's Hospital, also highlighted the importance of community health workers. As co-founder and CEO of Last Mile Health, Panjabi recruits, trains and equips community health workers to provide health care in their own villages.

"The impact of community health workers is incredible," Panjabi said. "Without these rural frontline workers, we cannot combat modern plagues."

The panel "The Science of Plagues" examined the science that drives both the prevention and treatment of plagues. The panel included, from left, George Armah, an associate professor of electron microscopy and histopathology at the University of Ghana; Gabriel Fitzpatrick, a public health physician and chairman of Médecins Sans Frontières in Ireland; and Bryan Grenfell, the Kathryn Briger and Sarah Fenton Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Public Affairs at Princeton. (Photo by Angela Halpin for Princeton University)

Sharing information, responsibility and success stories

These workers are especially important in terms of educating their peers. Fear, hysteria and stigma surround enigmatic diseases. Many are terrified to come forward, concerned about community perceptions.

"Stigma stops people from seeking treatment. If you were the first case, you wouldn't want to say, 'I have AIDS' or 'I have Ebola,'" Anne Case, Princeton's 1886 Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, said during the "History of Plagues" panel. "Stigma is a sister to fear. It is another way in which the disease is able to spread."

Part of the stigma and fear is created by media reports and the spread of information. In many cases, the epidemic was shaped by unnecessary hype, alarm and panic.

"Today, information spreads so quickly. That's great because information is crucial, but there is a hyping of a crisis that induces panic. This is unnecessary panic, which is counterproductive when you are trying to prevent the spread of disease," Cormac O'Grada, professor of economics at University College Dublin, said during the "History of Plagues" panel.

To better control epidemics using information technology, national and international coordination is needed, several speakers concluded. Protected data should be readily available to make smart and informed decisions.

Cecilia Rouse, dean of Princeton's Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, served as master of ceremonies for the Fung Forum and moderated the final panel, "After the Plague," which assessed the impact of the Ebola crisis and lessons learned. (Photo by Angela Halpin for Princeton University)

"In thinking about what to do going forward, we should consider privacy by design," Matthew Salganik, a Princeton professor of sociology, said during the "Disease and the Information Highway" panel. "For example, the general approach is to collect lots of data and try to protect it. A better approach would be to collect data in a way that, were it to be released, it wouldn't do harm to people."

"We need national and regional agreements on standard operating procedures related to data. You need to have people using systems as ongoing systems," said Christopher Fabian, co-creator and co-leader of the Innovation Unit at the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). "We need to invest in building technology in countries that are damaged and weak." Fabian deployed a text-messaging service that was used across West Africa to educate residents about the disease.

In terms of implementing solutions, panelists urged the importance of being realistic and strategic.

"There are many things that are desirable that may not be feasible," said Angus Deaton, Princeton's Dwight D. Eisenhower Professor of Economics and International Affairs and the 2015 Nobel laureate in economic sciences. "Throwing money at these problems without dealing with more fundamental problems will have unintended consequences."

The Fung Forum provides many opportunities for the exchange of ideas. Above, Jennifer Browning, left, who works at the World Food Programme and earned a Master in Public Affairs at Princeton in 2013, talks with Adel Mahmoud, a lecturer with the rank of professor at Princeton's Woodrow Wilson School and Department of Molecular Biology. (Photo by Angela Halpin for Princeton University)

Future responses need to be a global effort, panelists concluded. During his Nov. 3 keynote address, Farrar explained that global health is shifting away from the "old paradigm" of dominant countries being in charge, and the need for cooperation is more apparent now than ever.

"We need global health leadership. It needs to be a collective. There are only a small number of organizations who have the capacity to respond on a global scale; we can’t rely on the U.S. alone. The world needs to step up," Farrar said.

Even though the discussions focused on the lessons learned, powerful success stories also were brought to the surface. Many panelists agreed these stories should be leveraged to the serve the public good.

"There were people who went to health facilities and got first-class care," Barry Andrews, CEO of GOAL Ireland, said. "We are trying to bring people to the villages to tell those stories, to reaffirm that there is an appropriate health facility and appropriate data collection. We need to reaffirm that there were positive stories and for those stories to be told."

"Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) tries to keep the patient at the center of everything," said Gabriel Fitzpatrick, chairman of MSF Ireland. "You'll rarely get in trouble if you keep the patient at the center."

Several students involved with Princeton's Global Health Program (GHP) also attended the forum and were able to network with some of the world's top public health experts during their two-day stay.

"In our GHP curriculum, we're reminded in our lectures and in the program's structure to take an interdisciplinary approach to health challenges," said senior Jamie Shenk. "This conference really showed what that looks like in action. The forum brought together the foremost experts in each sector related to the Ebola outbreak — from Nobel laureates, to historians, to on-the-ground responders — to talk about what happened, the lessons learned and how to move forward. As a student, that was the most powerful aspect of this conference — watching and participating in such a high-level discussion."

During his concluding remarks, Eisgruber touched on the recurring themes of the conference: the ability to act quickly during an outbreak, truly understanding the local epidemic and knowing which solutions are feasible.

"What a remarkable two days it has been. Our panelists have taken us quite literally from the first vial of laboratory research … to the last mile of health care delivery and covered a great deal in between," Eisgruber said. "The conversations have been far too rich, too varied and too contested [to summarize] — and they should be contested with the difficult subjects like the ones we've described."

Visit the Fung Forum website for more information about the event. Videos of the panels and keynote speeches are available on YouTube.

The Fung Forum was held in O'Reilly Hall at University College Dublin. (Photo by Angela Halpin for Princeton University)