When one is already in possession of the world's oldest chunk of ice, perhaps it's only natural to want to go older.

John Higgins, a Princeton University assistant professor of geosciences, led a team of researchers who reported in 2015 the recovery of a 1-million-year-old ice core from the remote Allan Hills of Antarctica, the oldest ice ever recorded by scientists. Analysis of the ice showed that the concentration of carbon dioxide in the Earth's atmosphere was higher than in the oldest ice core previously, which was 800,000 years old. It also confirmed that atmospheric carbon dioxide and Antarctic temperatures have been directly proportional — as one increased so did the other. The ice is stored in Princeton's Guyot Hall in a freezer kept at -30 degrees Celsius.

But Higgins wants to go further back in time. He and four other researchers returned to the Allan Hills for seven weeks from mid-November to mid-January hoping to come away with even older ice, preferably 1.5 million to 2 million years old. The work is supported by a $700,000 grant from the National Science Foundation.

"We're currently in possession of some of the oldest ice that's been dated and we want to push that further," Higgins said in November, days before he and his team took off for the Allan Hills via New Zealand. Gases such as carbon dioxide and methane trapped in the ancient ice could provide clues about conditions on Earth in the distant past — and what they could be in the future if greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise.

Higgins traveled with research specialist Preston Kemeny, graduate student Yuzhen Yan and postdoctoral researcher Sean Mackay, all in the Department of Geosciences, and drill operator Mike Waszkiewicz of the U.S. Ice Drilling Program. The five men endured the harsh open ice shelf, camping an hour flight by prop plane from McMurdo Station, the research center on the Ross Ice Shelf operated by the National Science Foundation.

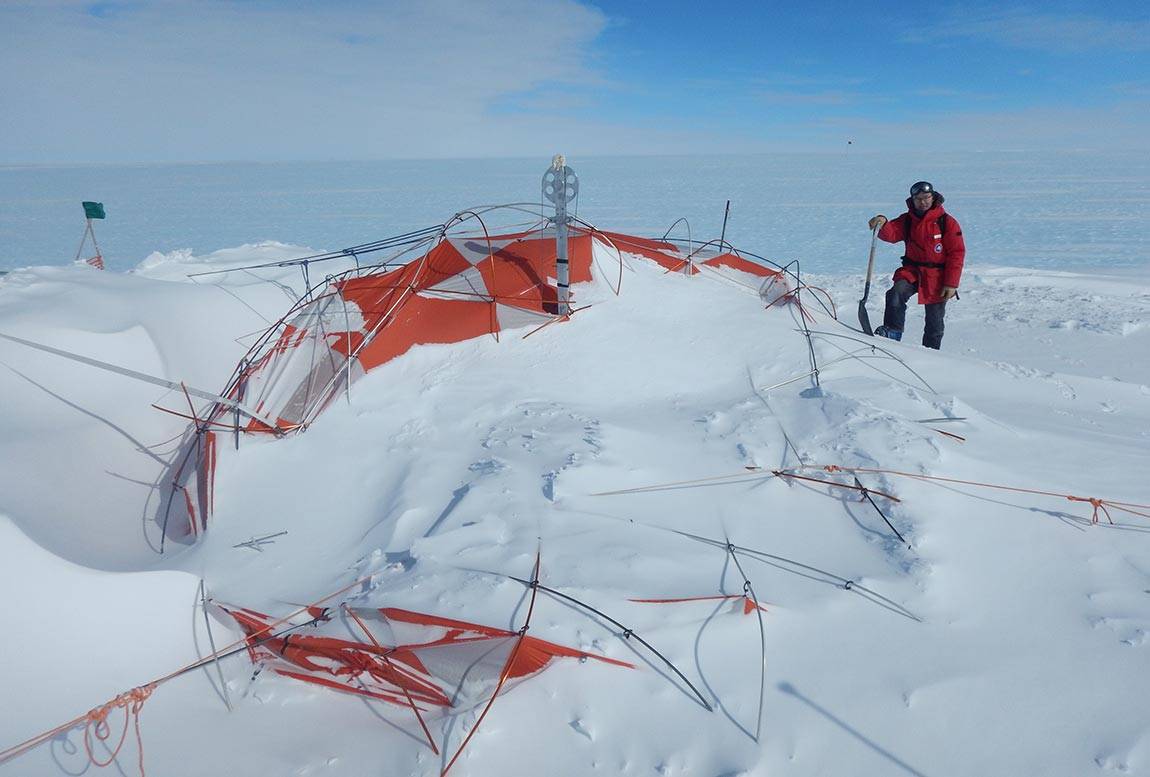

Temperatures hovered around -15 degrees Celsius, despite it being the height of the Antarctic summer. Winds sustained a speed of 25-30 miles per hour, slightly less than a tropical storm. Storms lasted five days straight and left behind drifts 12 feet tall.

The photo and video essay below captures the researchers' experience in one of the world's most unforgiving places, and explains the techniques and significance of their work.

The Princeton team camped for seven weeks on the barren blue ice of the Allan Hills. Strong winds here scour away ice at the surface, bringing up ancient ice from the depths like a giant conveyer belt. "We're letting the glacier do the work for us by bringing the old ice to the surface," Higgins said. For the same reason, blue-ice areas such as the Allan Hills have long been studied for their extraordinary accumulation of meteorites. (Photo by Preston Cosslett Kemeny, Department of Geosciences)

The researchers' camp was in the Allan Hills, about 130 miles northwest of the National Science Foundation's McMurdo Station research center. The team spent two weeks at McMurdo safe-checking their equipment and gathering supplies. The initial journey to the camp was done in four one-hour trips by plane, moving a total of four tons of goods and gear, Higgins said. The drill and associated equipment alone weigh about one ton. (Illustration by Maggie Westergaard, Office of Communications)

Preston Kemeny (pictured), a research specialist in the Department of Geosciences who was in Antarctica for the first time, carries an ice auger and marker flags. The invaluable research experience of being in the field in Antarctica comes at the cost of spartan living in a harsh, isolated environment. "It's stunningly beautiful and there's a tremendous amount of science to be done," said Kemeny, who received his bachelor's degree in geosciences from Princeton in 2015. "But it needs a lot of logistical support." A plane from McMurdo Station delivered supplies to the camp each week, weather permitting. (Photo by Sean Mackay, Department of Geosciences)

The work Higgins published in 2015 showed that when deployed in the right location drilling shallow cores 100-200 meters long could retrieve the old ice scientists need to understand Earth's past climate without drilling several kilometers into the ice sheet. Higgins and his colleagues came away with the million-year-old ice after drilling 128 meters. The researchers particularly want to go further back in time now to understand a period more than 1 million years ago when ice ages occurred every 40,000 years as opposed to the 100,000-year cycle of the past 800,000 years. "That's a massive change in Earth's climate system," Kemeny said. (Photo by Yuzhen Yan, Department of Geosciences)

The team had three drill sites that they would travel to by snowmobile, hauling the drilling equipment and tent between sites. The team spent all day at the drill site, monitoring the stop-and-start process while trying to stay warm. Only two or three other research groups undertake this kind of fieldwork, said Higgins, shown above carrying a drill bit filled with an ice core. "It's a minority who have deep-field camps and a smaller minority doing their own drilling out there," he said. (Photo by Yuzhen Yan, Department of Geosciences)

The researchers finally returned to one of the drill sites after the days-long storm to find that their work tent had been destroyed. In the photo above, geosciences graduate student Yuzhen Yan stands ready to dig out the drilling equipment. The researchers ultimately obtained three ice cores: two that are 98 and 205 meters long, respectively, and a 20-meter core from the same drill hole as the million-year-old core. Altogether, the cores weigh 4.5 tons, Higgins said. Packed in individual freezer chests, the ice samples will arrive in the United States from Antarctica in April via Los Angeles then be shipped to the National Science Foundation's National Ice Core Laboratory in Denver. Higgins and his team will begin determining the age of the ice cores in early summer, examining 500 grams of ice per day — or 14 to 15 centimeters of ice core at a time. "If things go well, by next winter we'll have a good idea of how old the ice is," Higgins said. Once the age of the ice is determined, the researchers will work with collaborators to measure the composition of chemicals such as carbon dioxide and methane. (Photo by Preston Cosslett Kemeny, Department of Geosciences)

Yan, on his first trip to the southern continent, packs a shipping container with snow to insulate the ice cores and prevent them from melting in transit. The white box weighs nearly 200 pounds and contains nine core segments measuring approximately 30 feet altogether. Despite the all-day sun of the Antarctic summer behind Yan, exposed skin can become frostbitten or, to a lesser extent, frost "nipped" in a matter of minutes. "To do deep fieldwork in Antarctica, you have to be pretty scientifically motivated," said Higgins, for whom it was his third trip to Antarctica. "It involves long time commitments in less than ideal conditions." (Photo by Preston Cosslett Kemeny, Department of Geosciences)

The researchers will date the ice using a technique developed by Michael Bender, Princeton professor of geosciences, emeritus, and Higgins' former postdoctoral adviser. The bubbles in the ice contain trapped ancient air, approximately 1 percent of which is the noble gas argon. The researchers compare the abundance of the three stable isotopes of argon (Ar) — 36Ar, 38Ar and 40Ar — in the trapped air relative to the modern atmosphere. Because 40Ar (but not 36Ar or 38Ar) is continually added to the atmosphere through volcanic emanations from Earth's interior, samples of ancient air from ice cores will contain less 40Ar — but the same 38Ar and 36Ar — than the modern atmosphere. The greater the deficit of 40Ar in the sample, the older the air, and, thus, the older the ice. (Photo by Yuzhen Yan, Department of Geosciences)

Base camp is a "small-family situation" of people confined to small tents striving to stay busy, keep warm and get along, Higgins said. "Everyone got along really well," Higgins said. "It's Antarctica, so it's never going to be especially pleasant." The isolation can be perilous in an emergency. In 2010, Higgins developed a severe toothache. He hopped an hour-long resupply flight back to McMurdo Station where he had a root canal performed. He returned to camp on the next supply flight a week later. (Photo by Sean Mackay, Department of Geosciences)