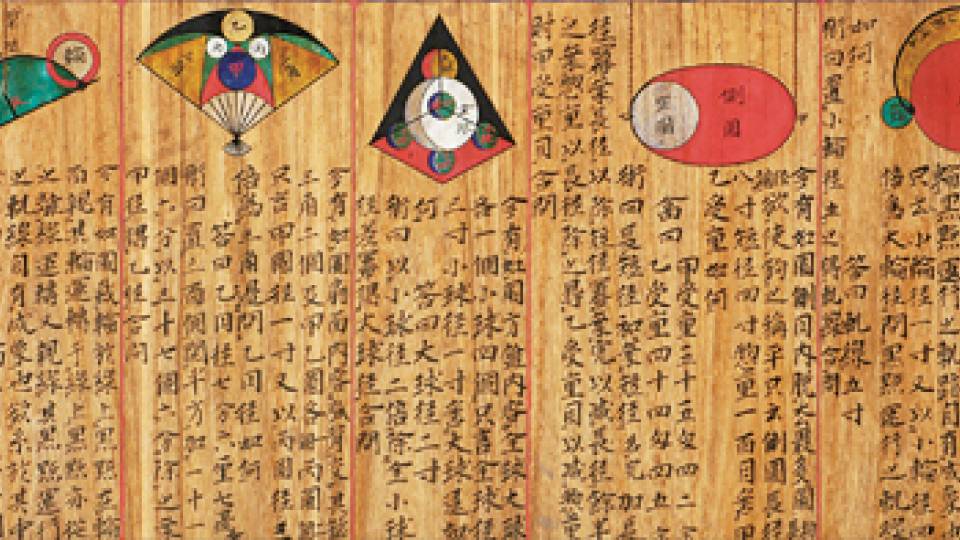

Thomas Conlan, a Princeton professor of East Asian studies and history, and Princeton University Library's Japanese Studies Librarian, Setsuko Noguchi, uncovered rare Japanese medieval documents from Sakuramotobō, a famous temple in Yoshino, Nara prefecture. Pictured are the documents upon arrival to Princeton.

In 2015, Thomas Conlan, a Princeton professor of East Asian studies and history who specializes in Japan, sought a set of “komonjo,” or Japanese medieval documents, for his graduate seminars in ancient and medieval Japanese history. As he often did, he collaborated with Princeton University Library (PUL) Japanese Studies Librarian, Setsuko Noguchi, to acquire a collection that his students could study and transcribe. The two purchased a set of documents from Yoshino, Nara prefecture in Japan, but what they found was rarer and more significant than they ever anticipated.

The documents originated from Sakuramotobō, a famous temple which lodged pilgrims who ascended and worshipped its nearby mountains and a center for Shugendō, a belief system that centered on mountain asceticism. Sakuramotobō, one of many temples founded in Yoshino in the seventh century, suffered because the Meiji government declared that native “Shintō” shrines and Buddhist temples should be distinct. As a result, Shugendō was banned. Many old records were lost, including the earlier Sakuramotobō documents.

“This mountain worship has left very few sources,” Conlan said. “What happened was in 1868, the Japanese government declared this to be a heretical set, and a lot of these records were destroyed. Some things survived, maybe the link to political leaders. But these kinds of documents don’t survive otherwise.”

Discovery and preparation

Before purchase, they learned that a set of documents from Yoshino contained items dated from the 14th century to the 17th century, including five 14th- and early 15th-century bills of sale from women to other women, which are unique. For centuries, the documents were forgotten, serving as insulation for a fusuma paper sliding door, and the sellers themselves were unaware of the items’ content.

“That’s the other irony about this,” Conlan said. “[The documents were] cherished for a long time, for centuries after the original creation. But after about 500 years, [they] use[d] it for the door ... and that allowed it to survive that very dangerous moment.”

When the materials arrived at Princeton, they were heavily disorganized, wrinkled and fragmented. The pair worked with Ted Stanley, special collections paper conservator, PUL Conservation Department, and other Japanese scholars on campus to prepare the documents for Conlan’s classes, humidifying and flattening the fragments. It was then that they noticed the documents’ origin. Immediately, the team postponed using them in the classroom and instead decided to conduct further research.

But preparation was half the battle.

In July 2018, Conlan and Noguchi invited four researchers from the Historiographical Institute at the University of Tokyo (HITU) — Masaharu Ebara, Yasufumi Horikawa, Akihiko Takashima and Akiyoshia Tani — to help identify the nature of the documents, organize the materials and transcribe the content. Takashima, a paper conservator, and Stanley teamed up to identify each document’s paper origin, reuniting several fragments based on the paper’s fiber structure.

At the PUL Preservation Lab, Tani photographed each fragment, while the rest of the team organized the fragments and accompanying data. Ebara and Horikawa, professors of medieval Japanese history at the University of Tokyo, read each item, transcribed the oldest fragments, and reunited 13 documents in the process.

Findings

In total, the boxes purchased contained 119 separate documents, 55 of which were written between 1308 and 1615. The remainder were written after 1615 with the last documents in the set dating from the late 17th century.

In the collection, the earliest dated occurrence of the name Sakuramotobō predates the oldest year recorded in the temple’s official history.

Many documents were addressed to the Sakuramotobō temple itself or to individuals affiliated with the temple. Sixteen documents relate to the activities of visiting Yoshino Mountain, such as tour fees and lodging arrangements, which show the relationships between Yoshino Shugendō, worshippers, guides and tours. Scholars of Japanese history and religion previously knew of only six such documents, and Princeton’s papers are older than the documents that were known.

For the team, it was particularly interesting that many documents were written by women and that the papers exchanged between women were of better quality than those exchanged between men.

The collection also allowed them to reconstruct connections between Sakuramotobō and other temples, centers and provinces in Japan. Deeds for property and letters of credit were also included in the set, documents useful for economic historians.

Future

For Conlan, Princeton’s acquisition will “allow [the documents] to be known and accessible in a way they probably wouldn’t have [otherwise] ...” Going forward, the team hopes to build further awareness of and accessibility to the new sources.

PUL's East Asian Library will organize the collection in chronological order, then match each item to its respective transcription, and later add the materials to the Library’s catalog. The Conservation Department, along with HITU, will work on future preservation, finding the best practices and storage methods (such as how fragments of the same document should be handled). As the documents frequently refer to geographical data such as location of temples, Noguchi hopes to work with the PUL Maps and Geospatial Information Center to create supplementary maps.

Once the documents are ready, Conlan and his graduate students will work on translations. The team aims to organize a conference to share their findings with the University community. They also hope to invite to campus a Shugendō specialist who can further compare Princeton’s material with existing official records of Sakuramotobō.

Ultimately, the goal is to digitize the documents so that these rare primary sources inspire further research in an area of studies that historically lacks materials of this kind.

At Princeton, the research project was funded by Princeton University Library, the Department of East Asian Studies, and the Program in East Asian Studies. The Tokyo Partnership Funds also contributed to the project.