Princeton University undergraduate students demonstrate a new level of commitment to environmental conservation as they serve in research, volunteer and internship positions around the world.

Determined to be guided by local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and mentors, these students dive into projects directed by grassroots groups, trusting that those on the ground know their needs best. As one student characterized it, they do the work that is needed when it is needed.

The University fosters such work, providing opportunities to serve across the globe each year. Students thrive in these culturally immersive projects as they resolve to contribute to Princeton’s unofficial motto: “In the Nation’s Service and the Service of Humanity.” Below are the stories of several students whose experiences abroad shaped who they are today.

Kisara Moore, Class of 2022, sifts buckwheat in Kunming, China.

Kisara Moore, Class of 2022

Bridge Year program, Kunming, China

Kisara Moore wanted to take a gap year in China, but not the global-powerhouse China, “not the kind of China you’d see in brochures.” Princeton’s Bridge Year Program was an ideal fit. She went to Yunnan Province in southwestern China where she participated in two environmental projects. Life in China exposed her to both multinational banks and government workers overseeing a massive infrastructure project as well as the tiny village of Lisichong — population 50 — where women of the ethnic Miao minority taught her traditional dances. And didn’t laugh at her singing.

At the Yunnan Green Watershed Management Research and Promotion Center, Moore translated phone conversations and articles into English. She shot and edited short films featuring conversations between NGO workers and the local people, whose quality of life is impacted by the Belt and Road Initiative underway across Southeast Asia. “Green Watershed is concerned their voices won’t be heard,” Moore said.

She also helped design classes and workshops for the Miao women through Eco-Women, a project that educates women in rural communities on environmental sustainability and farming practices. Most of the farmers are women, as the men are usually away from the village working in industrial jobs. Pesticide use is a worrisome issue.

“Along with the environment, we were focusing a lot on the fact that villagers were losing touch with their cultural heritage through the impact of globalization and modernization,” said Moore. “I would document the village women dancing traditional Miao dances, making traditional crafts like jewelry or quilts or cloth material, or speaking the Miao language. That was definitely a highlight of my time there. They were so welcoming to me. They don’t have a lot of access to food and they shared everything they had.”

Moore is now a first-year student at Princeton. She is considering pursuing a degree in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

“These experiences have made a profound impact on my values and worldview,” she said. “I’ve gained a new appreciation for nonprofits and the importance of their work after seeing just how dedicated they are to what they do. I’m confident these insights will continue to shape and develop me as an individual while I’m at Princeton.”

Maria Stahl, Class of 2020, at the Mpala Research Centre in Kenya.

Maria Stahl, Class of 2020

Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI) Summer Internship Program, Mpala Research Centre, Kenya

Each morning this past summer, Maria Stahl headed out to the veldt around the Mpala Research Centre in Kenya with a list of 15 to 20 plants she would forage that day. Along with others in the research group of Robert Pringle, an associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, Stahl would pile into a green Ford Ranger and go out in search of Solanum nigrum, Eragrostis regidor and other samples of indigenous grass species. She was part of a larger effort to create a database of all the plants at the reserve. Studying their characteristics, explained Stahl, might give scientists clues about the herbivores that live off of them and the dietary adaptations impala, zebras, elephants and other herbivores develop as climate change impacts plant life.

Stahl was at Mpala on an eight-week summer internship through the Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI). The experience helped her mature as a scientist. Out in the field, she said, there is no one looking over your shoulder to give you advice or guide your decisions. It made the lab work of logging plant species and characterizing their traits more meaningful. And it polished a skill set she had begun working on the year before, during another environmental internship.

“One of the greatest things about Princeton, I think, is the opportunity that students have to go to various places through different programs,” Stahl said. “I’d heard about the Mpala Research Centre in Kenya and really wanted to check it out and explore this new landscape. Since I really enjoyed the work I had done in Mozambique with Professor Pringle the summer before, I thought it would be interesting to have comparisons between these two ecological sites while also exploring a new region of the world.

“These experiences have taught me that I really value hands-on, outside field work,” she said, adding that she plans to take a year or two off before graduate school to pursue conservation work. “It has been really cool to see the different forms that science can take, and to hear from grad students and other researchers about the paths they’ve taken to get where they are.”

Peter Taylor of the Class of 2022 in Cochabamba, Bolivia, with Oscar Olivera, founder of the NGO Fundación Abril.

Peter Taylor, Class of 2022

Bridge Year Program, Cochabamba, Bolivia

It’s all about language for Peter Taylor. Creative writing. Linguistics. Comparative literature. Foreign languages. Language was a main motivator for Taylor’s Bridge Year in Bolivia, where he enjoyed the mesh of cultural and linguistic experiences and added two indigenous languages to his quiver of word-based skills. But most of the work was on the ground level. Quite literally.

Volunteering in the city of Cochabamba, Bolivia’s fourth-largest city, Taylor was “thrilled” to find himself working with Oscar Olivera, founder of the NGO Fundación Abril and a former leader and activist in the Cochabamba Water Wars that flared 18 years ago in response to the city’s privatization of municipal water. Under the auspices of Fundación, Taylor built water tanks and cisterns at local schools an hour outside of the city, which entailed long hours digging ditches.

“I was really glad to be doing something that was very much at the bottom of the organization. Because I was a volunteer, I was the grunt of the group,” Taylor said. “And I was happy doing whatever was needed.”

Later in the year, Taylor was tasked with repairing and re-growing a large garden used by a school in the suburb of Sacaba. After a “giant” mudslide overwhelmed and broke a canal surrounding the garden, he spent several days down in the trenches, shoveling mud and repairing the canal with other NGO volunteers. It taught Taylor a great deal about true service, and about doing the work that needs to be done.

“You’ve got to go somewhere and see what’s happening already, and make yourself useful,” said Taylor, who will pursue a degree in comparative literature. “It’s not about going and doing what you think needs to be done. The way I see it now, I wasn’t down there volunteering. I was going down to learn and also be a part of it in the way they needed. They loved teaching me and having me be a part of it. But the work we were doing together … they didn’t need me in the traditional sense, at all. Or any of us. It was a way to do really productive service work by just being available, being ready for those who knew what they were doing to tell me what I could contribute.”

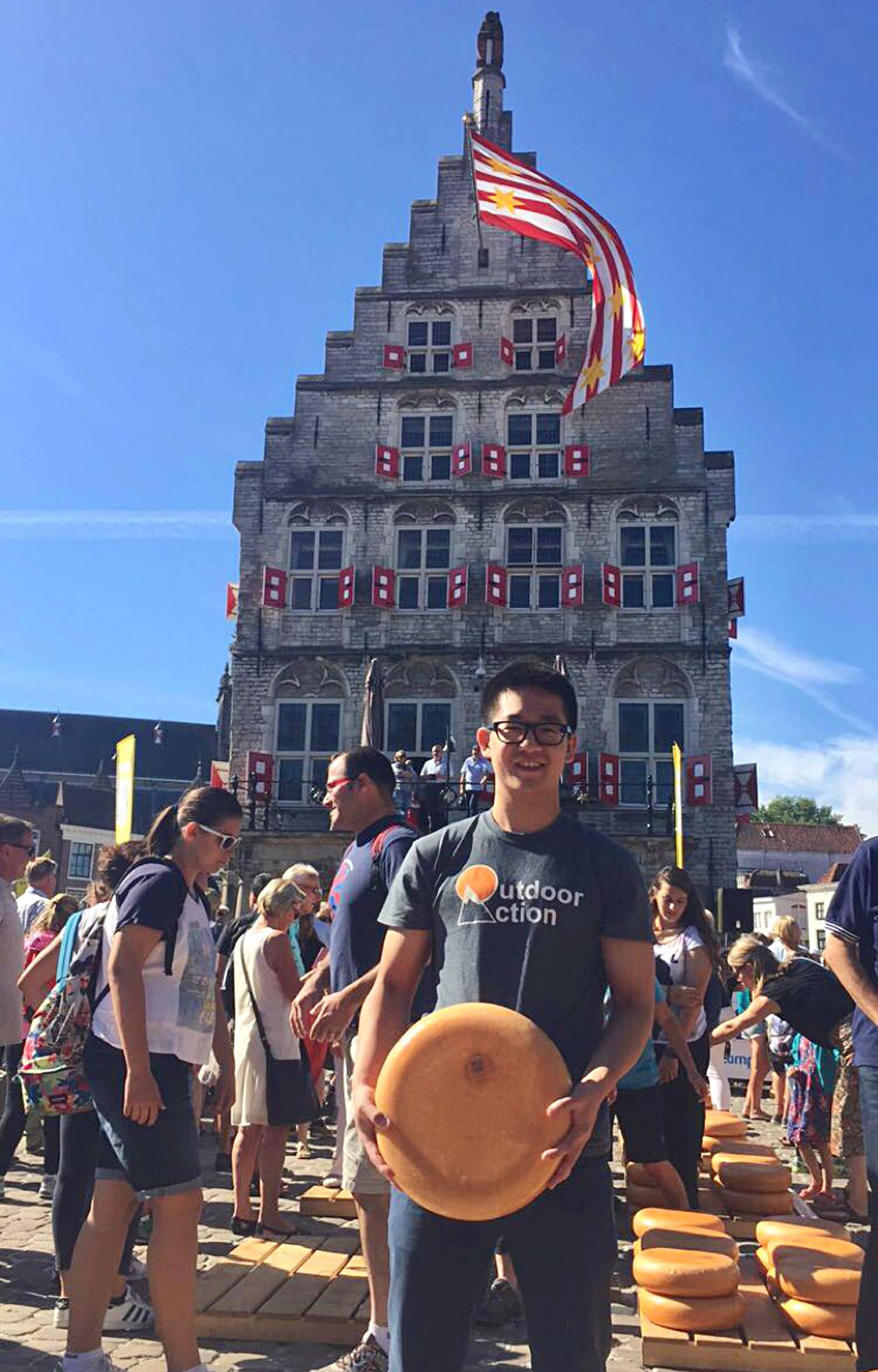

Lap Hei Lam, Class of 2021, in Lima, Peru.

Lap Hei Lam, Class of 2021

International Internship Program, Lima, Peru

It wasn’t until the flight abroad that Lap Hei Lam — six days after finals, two days after visiting his family in Connecticut, and one day after driving to New York for departure — really let it sink in: he was headed to Peru as a summer intern for Planeta Océano. On the ground in Lima with 18 other interns, Lam worked on a couple of locally driven projects. The main project involved teaching leadership skills to schoolchildren through the lens of environmental sustainability. Another centered on an environmental exhibit about issues affecting the ocean. Lam addressed everything from manta rays to overfishing to plastic waste, eventually contributing to 40 pages of documents directing the exhibit’s installation.

But perhaps most instructive of all, Lam says, was a side trip to Tarapoto, a hunting-and-farming community in the Amazon that had largely depleted its natural resources. A group of local volunteers helped redirect Tarapoto’s small economy towards ecotourism, which Lam saw as an essential pivot and a community-wide lesson in cooperation. “The transformation yielded spectacular results and made clear how impactful conservation can be,” said Lam, who is considering majoring in civil and environmental engineering.

In the end, the Peru internship fulfilled Lam’s hopes to bear witness to volunteerism on a local level. But that was simply the beginning, he explained

“Now, I want to think about how I can contribute to the challenge of environmental degradation,” Lam said. “But I would also like to see how the corporate level handles things — oil, propane, natural gas — because it’s always very different from the way the media portrays it. It’s very important to see both sides of the issue.”

To that end, Lam is applying for an internship next summer on the corporate side.

“Companies claim they’re investing more in clean options, but to what extent are they really doing that? How far has it gone? Do they really mean it or not?” he said. “I want to explore the corporate side of it — if they’re going to change their approach through ever-growing pressure. I’m trying to reconcile those two sides of one important issue.”

Kim Sha, Class of 2019, in Bochum, Germany.

Kim Sha, Class of 2019

Keller Center International Research Exchange Program, Bochum, Germany

Over the past few years, Kim Sha has enjoyed internships that gave him an evolving perspective on the push-and-pull of innovation and policy, refining his sense of how environmental issues — including climate change — play out on many levels. It’s one of the reasons he came to Princeton in the first place.

“When I first got here, I was very interested in the intersection of engineering and innovation and the economics of a particular technology,” said Sha, who is majoring in chemical and biological engineering. “The initial research I did was laboratory-based and it was a little bit more difficult to see the real-time effect. This past summer was extremely inspiring, because I got to see the connections between what scientists are doing in the lab and what works in real life.”

He started out three summers ago with research on organic solar cells through the Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI). Then, after his sophomore year, Sha worked at the Institute for Materials at Ruhr-Universität Bochum in Germany, through Princeton’s Keller Center’s International Research Exchange Program, programming a general tool used to characterize materials. His work at Ruhr-Universität was lab-based and generative, and had a fundamental programming component.

This past summer, Sha worked at the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) in Chicago in collaboration with the nonprofit watchdog, Citizens Utility Board, in an internship set up through Princeton’s Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment. Sha’s work with the EDF was an extension of sorts of his internship in Germany, because it illustrated how lab-based research can be used to solve practical problems.

The combination of these internships, at home and abroad, helped to shape Sha’s viewpoint.

“I’ve learned so much about how the industry as a whole works from the ground up, from conception to development to research and design to pricing and policy,” said Sha, who is also pursuing a certificate in finance.

Asked if he believes his experiences make him more optimistic about the future of climate change and our ability to manage it, he tempered his response. “I would say ‘qualified optimism.’ With the kinds of issues we have today, it’s very difficult to promote specific policies,” he said. “But there’s potential there. Especially if our infrastructure continues to develop.”

This story was published in Princeton International Magazine.