Tullis Onstott, a Princeton graduate and professor of geosciences known for his innovative research in several specialties and his explorations of lifeforms deep below the Earth’s surface, died Oct. 19, 2021, in Oracle, Arizona, from complications associated with lung cancer. He was 66.

Tullis Onstott

Onstott, who earned his Ph.D. at Princeton in 1981, was a member of Princeton’s faculty for 37 years. For the past several decades, he focused on subsurface microbial life and ecosystems via mines, drilling and new underground laboratories at some of the deepest sites across the globe.

Notably, he led a team of researchers that in 2008 discovered the microbe Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator almost two miles below the Earth’s surface in a South African gold mine. In 2011, he co-discovered Halicephalobus mephisto, a nematode worm living 0.56-2.24 miles underground, the deepest multicellular organism known to science.

“Tullis Onstott’s many friends in GEO and the geosciences community in the U.S. and abroad will grieve the loss of their colleague, TC,” said Bess Ward, the William J. Sinclair Professor of Geosciences and the High Meadows Environmental Institute, and chair of the Department of Geosciences. “Although far too young when he died, TC was one of the longest serving members of the department; having done his Ph.D. here, he returned after a postdoc to spend the entirety of his professional career in this department.”

Ward said Onstott’s research career was more varied than most, his journey taking him from geophysics and paleomagnetism to biogeochemistry and microbiology, which “earned him friends and colleagues at every step.”

“They will all remember his enthusiasm and curiosity about everything, his fearless dives into new and challenging problems and his always youthful smiling countenance,” Ward said. “He was admired by many and will be remembered and missed by all.”

Onstott is the author of “Deep Life: The Hunt for the Hidden Biology of Earth, Mars, and Beyond” (2016, Princeton University Press) and more than 170 scholarly papers.

Most recently, Onstott’s research group has been involved in four field projects investigating bacteria/rock/environment interactions: two in the deepest mines in North America and South Africa, one in Siberian permafrost deposits, and another in shallow groundwater sites in New Jersey.

Without reliance on sunlight or other organisms, subsurface microbes inhabit water-filled cavities inside rocks and acquire the energy they need from chemical reactions caused by the natural radioactive decay in minerals.

Among the questions explored by Onstott and his team were how subsurface microorganisms evolve, what constrains their diversity and abundance, and what role does radiation play as an energy source for life. His group also addressed how the methane and nitrogen cycles interact in the subsurface, and how global climate warming might impact the methane cycle in the Arctic and in Antarctica.

"Beyond his own research, TC was also deeply committed to science education," said Laurel P. Goodell, manager of the geosciences undergraduate laboratory. "For many years, he worked with local in-service teachers through QUEST and other professional-development programs run by Princeton’s Program in Teacher Preparation."

"He helped educators understand where and how organisms are able to live," Goodell, said. "He was so enthusiastic, patient and open to learn from teachers as well. His sense of humor, brilliance and passion were appreciated by all who knew him."

Early in his career, Onstott specialized in argon dating techniques, paleomagnetics and the crystal-chemical structure of minerals. He later pivoted toward questions of lifeforms that exist in seemingly inhospitable conditions below ground.

“He started doing this work with biology deep underground, and it was out of sight, crazy, different, really innovative,” said Robert Phinney, professor of geosciences, emeritus. “I’m sure that most people in geosciences, or for that matter, biology, would have said, ‘This is ridiculous. There’s nothing down there.’”

Proof that life existed below the Earth’s surface raised the possibility of discovering life beneath the surface on planets like Mars. In 2004, Onstott worked as part of a multi-institutional team that won a NASA grant to develop instruments that could extract evidence of microbes from beneath the surface of Mars.

Onstott was born on Jan. 12, 1955, in Carlsbad, New Mexico, to Margaret Allene and Tullis (Scotty) Onstott, who lived in Carlsbad since the early 1940s. The family moved to Ontario, Canada, and Las Vegas, Nevada, where Tullis graduated from high school in 1973.

Onstott earned his B.S. in geophysics at the California Institute of Technology and his Ph.D. in geology at Princeton under the supervision of Robert Hargraves. After receiving his doctorate, Onstott spent three years as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Toronto before returning to Princeton in 1985 as an assistant professor of geosciences. He was promoted to associate professor in 1991 and became a full professor in 2001.

“Tullis Onstott had contagious enthusiasm as he embarked on projects, and he maintained that enthusiasm through all the inevitable ups and downs that he would encounter as the project progressed,” said Lincoln Hollister, professor of geosciences, emeritus. “He had no fear of failure. His students worshiped him for his support and the respect he had for them.”

Satish Myneni, professor of geosciences, said Onstott was a “gentle soul, and very cheerful person.”

“He was always friendly to junior faculty and highly supportive of their work and needs,” Myneni said. “For every Christmas, his tradition was to hand-deliver bouquets to my colleagues in the department, and organize get-togethers for his group members at his residence. He cared about everyone in the department.”

Onstott was named one of TIME’s 100 Most Influential People in the world in 2007.

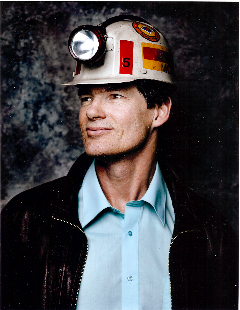

Onstott wears his headlamp and protective gear while excavating microbial life in some of South Africa’s deepest mines.

He received numerous awards including the Presidential Young Investigator Award (1985-1989); Jubilee Medal, Geological Society of South Africa (1988); Award for Meritorious Research in Subsurface Microbiology (1995), Award for Meritorious Research in NABIR Program (1998) and Appreciation Award for Research Excellence Office of Science (2002), U.S. Department of Energy; and the LExEN Award for his work “A Window into the Extreme Environment of Deep Surface Microbial Communities.”

Tullis is survived by his wife, Nora Anderson of Stockton, New Jersey; two sisters, Tullisse (Toni) Murdock, and her wife, KJ Spring, of Oracle, Arizona, and Pat Pinckert of Carlsbad, New Mexico; and three nieces, Allene Warren and Ruthie Brown both of Carlsbad, New Mexico, and Jan Smith of Wichita, Kansas.

Memorial contributions can be made to the Dr. Musa Manzi Foundation or designated to support the Planets and Life undergraduate certificate program founded by Onstott in the Department of Astrophysics at Princeton University.

View or share comments on a blog intended to honor Onstott’s life and legacy.