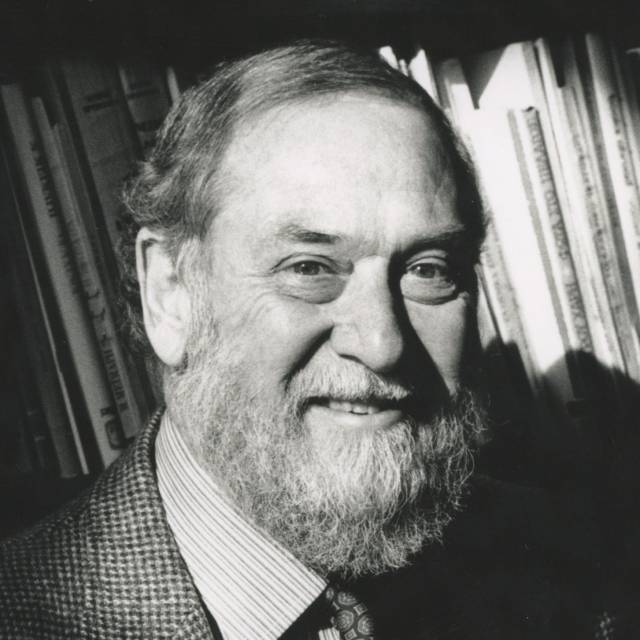

Edmund “Mike” Keeley, the inaugural Charles Barnwell Straut Class of 1923 Professor of English, Emeritus, and professor of creative writing, emeritus, poet and renowned translator of modern Greek poetry, died peacefully at home in Princeton on Feb. 23. He was 94.

Edmund "Mike" Keeley

Keeley, a 1949 alumnus, joined Princeton’s faculty in 1954 and transferred to emeritus status in 1994. He taught English, creative writing, comparative literature and translation at Princeton for 40 years and was instrumental in expanding the Program in Creative Writing, which he directed for 16 years, and in establishing the Program in Hellenic Studies.

“Mike was the preeminent scholar and translator of modern Greek poetry of our time,” said Dimitri Gondicas, the Stanley J. Seeger '52 Director of the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies. A 1978 alumnus, Gondicas entered Princeton in fall 1974 and met Keeley that semester. It was the beginning of a friendship that lasted nearly 50 years, until Keeley’s death.

Gondicas continued: “As president of the PEN American Center from 1991 to 1993, Mike was a champion of writers’ rights around the world. He was America’s most distinguished cultural ambassador to Greece. Closer to home, he was a founder and pillar of Hellenic studies at Princeton. Mike was our teacher, mentor, colleague, comrade in all things Hellenic, fellow traveler all over Greece, and steadfast friend. Until his last hours, Mike kept asking about Hellenic studies and our future plans.”

In 1982, Keeley received Princeton’s Howard T. Behrman Award for distinguished achievement in the humanities.

He was born on Feb. 5, 1928, in Damascus, Syria, to American parents, Mathilde Keeley and James Hugh Keeley, Jr., a career diplomat, and grew up in Canada, Greece and Washington, D.C. He first fell in love with the land, people and language of Greece as a child, when his family lived at the American Farm School, focused on environmental, agricultural and sustainability education, in Thessaloniki, while his father was the American Consul. He had two brothers: Robert Keeley, a 1951 alumnus and 1971 graduate alumnus, who entered the foreign service and served for a time as the U.S. ambassador in Athens; and Hugh Keeley, a 1946 alumnus.

During World War I, before Keeley was born, his father was the officer in charge at Princeton assigned to train the University’s unit of the Army air force. When Keeley entered Princeton in fall 1944 at age 16, there were just 40 members of his class, and he intended to enter the foreign service after graduation. After his first year, he went to Trenton and signed up for the Navy, on Aug. 7, 1945, the day after the U.S. dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. He spent a year as a seaman second class, based in Guantanamo.

When he returned to Princeton, Keeley fell in love with literature after taking an English course in Shakespeare and started writing poetry. He wrote his thesis on F. Scott Fitzgerald.

After graduation, Keeley returned to the American Farm School to teach on a Fulbright scholarship. He earned his doctorate at Oxford on a Wilson fellowship in 1952, writing his dissertation on the modern Greek poets C.P. Cavafy and George Seferis. He saw his foray into translation as a way of being a poet and an academic. At Oxford, he met his wife Mary Stathatos-Kyris, also a student of modern Greek. They were married for 61 years and frequently collaborated in translating Greek fiction and prose. They established the Edmund and Mary Keeley Modern Greek Studies Fund in 2004. Mary died in 2012.

“His belief in the humanities, even when sorely tested, proved unwavering,” said Maria DiBattista, who now holds the chair Keeley had, the Charles Barnwell Straut Class of 1923 Professor of English, as well as professor of comparative literature. “He loved most to talk about literature, about the authority and power of words before the most obstinate realities, the most obdurate, often contradictory but deep and thus precious feelings. He was the most companionable of men, his largeness of mind and heart exemplifying the Hellenic spirit that inspired his life and work.”

Keeley served as director of the Program in Creative Writing from 1965 to 1981. He once said he considered it a great reward when both he and his students were moved to tears by discovering something new in literature that touched their hearts. He also said he felt a great debt to the New Criticism, a major source for his work as a critic and teacher in his early years, promoting the close reading of fiction and poetry, as well as an important inspiration for his persistent belief in the value of the humanities. In 2016, the Lewis Center for the Arts established the Edmund Keeley Literary Translation Award, given annually to a promising young translator.

“Though it was founded as long ago as 1939, the Program in Creative Writing took on something of its present shape and significance only under the leadership of Edmund Keeley,” said Paul Muldoon, Howard G.B. Clark '21 University Professor in the Humanities and professor of creative writing in the Lewis Center for the Arts. “Inspired partly by the model of Iowa, he instituted the workshop as the key pedagogical component in the program, allowing students not only to write but, no less importantly, to read the work both of past exemplars and their peers.”

Muldoon continued: “Another key notion was that only the very best practitioners in the field be hired to teach workshops in poetry, prose fiction and literary translation. This last had a special place in Edmund Keeley’s heart, of course, since he himself represented the gold standard in translators of [modern] Greek poetry.”

One of these writing practitioners is the prolific Joyce Carol Oates, the Roger S. Berlind ’52 Professor in the Humanities, Emeritus.

“Mike had been the brilliant, tireless, often hilarious and irrepressibly charismatic director of the Program in Creative Writing when I arrived, in 1978, with the intention of teaching just one year; it is due to Mike that, in 2022, I am still here, and I am even teaching a workshop in advanced fiction this term,” said Oates.

She continued: “Mike and his beloved wife Mary were at the center of a most lively literary circle. At their wonderful parties, newcomers to Princeton were made to feel welcome amid a dazzling ensemble of writers, poets, professors, friends from both Princeton and New York; often there were distinguished visitors, members of PEN. In our community of famously congenial colleagues, Mike’s generosity was legendary…. His work, like his life, was suffused with a sense of purpose, and a particular sort of radiant joy in that purpose. He was one who had loved life — and whom life had loved in return.”

Keeley liked to swim in Dillon Gym. One day he ran into President William G. Bowen and asked if the University could use a supporting grant for a program to teach modern Greek. That conversation led to the transformational gift by Stanley J. Seeger, a 1952 alumnus, to create the Stanley J. Seeger Hellenic Fund in 1979, providing the foundation for the Program in Hellenic Studies, established in 1981. In 2011, the University formally named the Stanley J. Seeger ’52 Center for Hellenic Studies to consolidate and expand its research activities, international initiatives, scholarly exchanges and offerings in the classroom. Until very close to the end of his life, Keeley would return to campus for the weekly lunch at the center, where he enjoyed catching up with graduate students and colleagues.

W. Robert Connor, a 1961 graduate alumnus in classics and professor of classics, emeritus, traveled to Greece with Keeley to convince Seeger that Princeton would make good use of his generosity.

“I was nervous but Mike was, apparently, completely relaxed, and certainly completely persuasive,” Connor said. “Later, I came to realize that underlying Mike’s success in establishing this program, in steering the Program in Creative Writing, and in his own prose and poetry was a rich love of literature, and even more fundamentally a love of life itself.”

Alexander Nehamas, a 1971 graduate alumnus, the Edmund N. Carpenter II Class of 1943 Professor in the Humanities, Emeritus, and professor of philosophy and comparative literature, emeritus, called Keeley “the heart and soul” of the Program in Hellenic Studies.

“His translations and studies of the major modern Greek poets were essential to making them widely known in the English-speaking world,” Nehamas said, “His spirit was generous, his commitment to intellectual work profound, his love of good company infectious. He was my teacher, my colleague, and my friend, as he was to many others: we are all sad to have lost him.”

In 2016, the University added a formal home base for Princeton scholars in Greece with the opening of the Princeton University Athens Center for Research and Hellenic Studies, led by the Seeger Center.

Keeley was the author of eight novels; 15 volumes of poetry and fiction in translation; a memoir, “Borderlines”; 10 volumes of nonfiction; and two chapbooks of poetry. His career as a novelist was recognized at its start when his first novel, “The Libation,” won the 1959 Rome Prize of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and 40 years later, in 1999, he received the Academy's Award in Literature for "exceptional accomplishment."

He was a principal founder of the Modern Greek Studies Association in the U.S. and served as its first president. A leading guide to the beauty of modern Greek poetry, he translated, with Philip Sherrard, the collected poems of C. P. Cavafy and George Seferis, along with selected poems of Odysseus Elytis. Seferis and Elytis are Greece’s two Nobel laureates in literature.

His many awards for translation included the 1980 Landon Award of the American Academy of Poets for his translations of Yannis Ritsos; the 2000 PEN/Ralph Manheim Medal for Translation, given every three years to a translator "whose career has demonstrated a commitment to excellence through the body of his or her work"; and the 2014 PEN Award for Poetry in Translation, in collaboration with Karen Emmerich, for Ritsos’ "Diaries of Exile.”

Emmerich, a 2000 Princeton alumna, associate professor of comparative literature and director of the Program in Translation and Intercultural Communication, met Keeley when she was an undergraduate. He had already retired but occasionally came for class visits. “I was very much in awe of him,” she said. When she was a postdoctoral fellow at the Seeger Center, she mustered up the courage to ask him to collaborate with her on the Ritsos project one night while out to dinner with Gondicas and the Keeleys.

“Getting to translate Ritsos with Mike was one of the great pleasures and honors of my life,” Emmerich said. “He was like a steamroller bearing down on that project: I couldn’t stop working, either, because his pace was so furious …. Mike was such a careful, conscientious reader, with a beautiful sense of both languages. And his generosity to a young translator like me continues to fill me with gratitude.”

Rachel Hadas, a 1982 graduate alumna in comparative literature and the Board of Governors Professor of English at Rutgers University-Newark, became a lifelong friend and collaborated with him on a massive anthology, “The Greek Poets: Homer to the Present” (2010). In 2018, she wrote the introduction to Keeley’s “Nakedness Is My End,” a collection of his translations from the Greek Anthology.

“The poems Mike loved and rendered so beautifully in this last book are notably clear-eyed and calm (and sometimes playful) in facing the end,” Hadas said. “Mike himself seemed barely touched by age during our conversations in 2020 and 2021. The pandemic was all around us; it was pretty clear we wouldn’t see each other again. The poetry he loved and served for so many years had been preparing him all along. Mike is gone, but the poems abide and inspire us, as do our memories of this remarkable man, as (to quote “Mythistorema,” the Seferis poem that has always been my favorite) we ‘put to sea again with our broken oars.’”

Author and translator Daniel Mendelsohn, a 1994 graduate alumnus in classics, recalled: “While I was working on my own translation of Cavafy, Mike — rather than feeling threatened or competitive — would invite me to lunch at Prospect House every now and then to talk about my progress. We’d sit there for hours, bouncing around ideas for how to approach various poems.”

In 2001 the President of Greece named Keeley Commander of the Order of Phoenix for his contribution to Greek culture.

After his retirement, he continued to write fiction and poetry and to translate from the Greek, including epigrams from the Greek Anthology. At Seeger Center poetry events Keeley would enjoy reciting from his translations of modern Greek poetry. One of his favorites, Cavafy’s “Ionic,” is a poem which evokes the living spirit of Hellenism — ancient and modern — that spanned Mike Keeley’s own life and animates his work (from “C. P. Cavafy: Collected Poems,” revised edition, Princeton University Press, 1992):

That we’ve broken their statues,

that we’ve driven them out of their temples,

doesn’t mean at all that the gods are dead.

O land of Ionia, they’re still in love with you,

their souls still keep your memory.

When an August dawn wakes over you,

your atmosphere is potent with their life,

and sometimes a young ethereal figure,

indistinct, in rapid flight,

wings across your hills.

Gondicas said that Keeley was very happy to share with the world his penultimate poem, “Daylight,” his reflections on the pandemic, published in the summer 2021 issue of the Hudson Review. It was intended as part of a trilogy, along with "Pelion" and "The Day Comes" (his last poem), which the Hudson Review published in his memory.

Daylight

by Edmund Keeley

Our plague has various names

None as blunt as the Black Death

Of the Middle Ages yet still as dark

Unless you can somehow believe that light

From a flash of final recognition

Or anticipated otherworldly dawn

Will always arrive before the end

To mute the horror of so much dying

And your own waiting for what might come.

So why wait any longer,

Why not leave it all to Nemesis

And take a long walk outside

In whatever direction holds the prospect

Of your recovering things to remember

From those lighter years in open spaces

That shore beside an endless sea

The white mornings to lie in wonder

After the beautiful dark passages

Of nightlong loving and the dividends

Of having held another beyond

Any belief that it could possibly end.

The Edmund Keeley Papers are held in Special Collections at Princeton University Library.

Donations in Edmund Keeley's name may be made to the American Farm School in Greece. The U.S. address is: American Farm School, U.S. Office, 1740 Broadway, Suite 1500, New York, NY 10019.

View or share comments on a blog intended to honor Keeley’s life and legacy.