Last month’s Lunar New Year ushered in a Year of the Tiger, a moment of pride and reflection for Princeton’s vibrant Asian and Asian American community. Throughout the year, we will be elevating the voices of faculty, staff, students and researchers from the community in a series of thoughtful interviews exploring questions of identity, pride, hope, the lived experience of anti-Asian racism, and meaningful steps that allies can take.

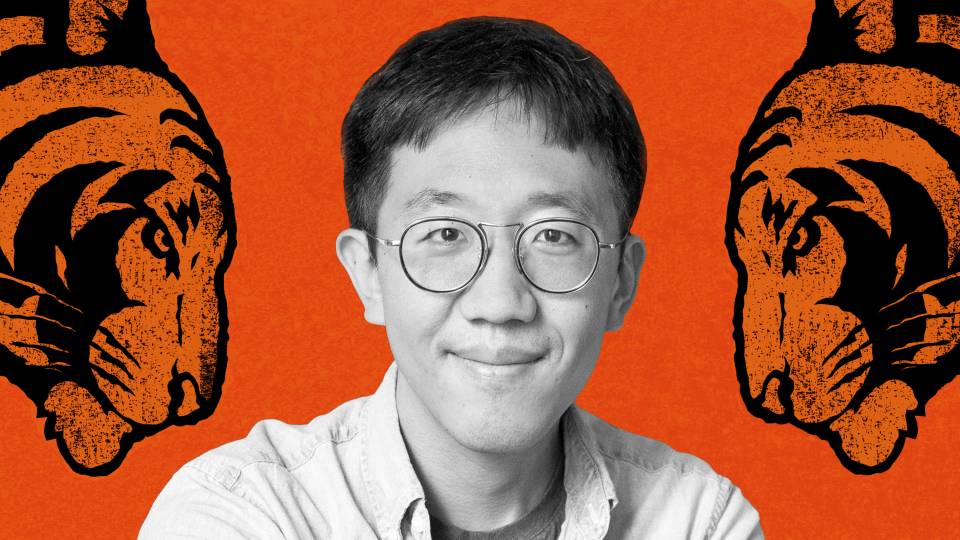

This month, we continue the series in conversation with Yi-Ching Ong, associate director at the John H. Pace, Jr. '39 Center for Civic Engagement and director of the Service Focus program for Princeton sophomores.

How do you self-identify?

The question of identity is so interesting to me because I was born to a family of immigrants and have had to navigate different cultural contexts throughout my life. It’s made me think a lot about how the answer to that question shifts in time, and depending on who you’re speaking with and where you are. So I want to start by sharing a bit about my family history, and then talk about how that’s shaped how I identify today.

Yi-Ching Ong

My parents were born in Malaysia, which prides itself on being a multicultural democracy. My mother’s grandparents and my father’s parents came from China. My parents spent time in England and in the U.S. for graduate school, then came permanently to the U.S. in 1979, driven by strong anti-Chinese sentiment in Malaysia that led to policies and quotas that would have severely limited our educational and professional opportunities. They chose to become American, and now my brother and sister and I are the first generation in our family to be born American.

I grew up in Indiana, in a community that was not particularly diverse. Like most kids, I was sensitive to social belonging, and I felt self-conscious about asserting difference. But in ways large and small, I found it mattered to me to be able to do so. For example, my sister Yi-Ping and I got quite a bit of teasing, and I remember how annoyed my we felt to be called Ping Pong and Ching Chong. But correcting people — sometimes multiple times — about my name became a small way to practice advocating for myself and representing an aspect of my heritage.

When I went to college [at Harvard], I found it really meaningful to have more peers with life experiences and family histories of immigration that echoed my own.

I would now say I identify as Asian American, but I have complicated feelings about that term. I think it has been very helpful in building a sense of solidarity and raising awareness about the many shared experiences that Asians and Asian Americans have faced in the United States related to harmful stereotypes, xenophobia and exclusion. But it also can be used in ways that aren’t helpful, and it can suggest homogeneity where it doesn’t exist. Asian Americans are incredibly diverse, in every way imaginable from religion to socioeconomic status.

When I say I’m Asian American to people who don’t know me, I always hope that raises more questions — about what I value, about what my and my family’s history and experience has been — than it answers.

I also think quite a bit about gender as an axis of identity: being female, and how that intersects with being Asian American. Societal expectations related to gender are so strong to begin with, and there are particularly strong norms in the Malaysian Chinese culture that my parents grew up in. There are also very deeply embedded expectations and perceptions of Asian American females here in the U.S.

The more overt incidents of personal racism I’ve experienced have often been related to these ideas. One very small example — I remember having to change my route between classes in college to avoid a group of men who routinely catcalled and shouted out greetings in various Asian languages. It was darkly comical in that none of those languages were the ones spoken in my own home. These types of experiences, and so many more — and worse — are distressingly common. There are so many ways that Asian American females are exoticized and expected to be compliant objects of desire. It’s definitely a very challenging piece of the way that stereotypes run in the United States.

What makes you proud to be Asian American?

I’m proud of my heritage, and proud to be the daughter of immigrants. Now that I’m older, with my own children, I appreciate in deeper ways than I ever could before what it meant for my parents to leave their own families of origin and set out to build a new life with us half a world away. My parents were quite clear-eyed about the challenges they would encounter. But they were also idealistic, in the best way possible. And I think that kind of idealism — about building a shared future that has space for all to inhabit — is such an important thing to celebrate and hold onto, even when we may seem far away from it.

I want my children to know their heritage and be proud of it, too. When my daughter entered preschool, we decided to send her to Yinghua International School, a Chinese immersion school, so she could get a bilingual base. I felt like I missed an opportunity to connect more deeply with my grandparents by not developing my language skills when I was young. Because my Chinese is very rudimentary and my husband has a different background, school was the only way to impart this to her.

She’s had a wonderful experience there, and it’s been heartwarming for me to see her connect with my parents in a different way because of it. I have this lovely memory from just before the pandemic — in January 2020 — of the school’s annual Chinese New Year celebration, when my parents were visiting. The children sang and put on skits, and there was a dragon dance and other festivities. Watching my parents, I could see them marvel at the long arc of time and confluence of circumstances that allowed their American granddaughter to celebrate Chinese New Year more fully than I was ever able to when I was young.

What can allies and others do to combat anti-Asian racism?

Allyship can take so many different forms, because anti-Asian racism — and racism in general — has so many different facets. It can be structurally codified in policies and practices. It can show itself in direct and personal ways, like the increased incidents of targeted violence against Asians. And it can circulate in narratives that shape people’s beliefs, perceptions and actions. We’ve seen a lot of that recently, as COVID has fed narratives that build on a history of ideas about Asians and disease. The past couple of years have been both painful and hopeful in that because anti-Asian sentiment has risen, we are now forced to talk more in the public arena about how it is real.

I think a lot about that last aspect of anti-Asian racism — the narratives — because I’m interested in how we all, as human beings, tell stories to make sense of our world and our lives. I’ve talked a lot about my own family history because I think that if we are curious and open to each other’s stories, it brings us closer to understanding other people on their own terms.

So one big area of allyship that I’d love to highlight is learning about Asian American history in a way that highlights the nuance and complexity it enfolds, and trying to extend opportunities for people to learn about it. It helps to illuminate where bias and discrimination exist in the present day, and where certain tropes keep surfacing again and again.

Are there examples from what you’re involved in to counter anti-Asian racism that you think would help others?

In my work at the John H. Pace ’39 Center for Civic Engagement, I feel really fortunate to be part of how Princeton supports students in the service of humanity. Students in our programs work alongside and learn from community partners, through full-time summer internships, or as volunteers during the academic year. Sometimes, there have been very direct opportunities for students to learn about and address anti-Asian racism.

For example, some of our students have interned with community partners like the Museum of Chinese in America or Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders in Philanthropy. These have been meaningful opportunities to learn from leading advocates and practitioners, and I’d certainly encourage anyone interested to connect with and support organizations like these that are doing strong work in this area.

But I also see students learning skills and habits of mind that will help them to counter racism through other kinds of experiences. In all of our programs at Pace, we strive for service to not only be a short-term response to need, but also to lead to a deeper understanding of — and capacity to recognize and respond to — complex societal issues, including racism.

We guide students in preparation and reflection so that they can critically interrogate what they observe. We ask them to think carefully about how historical and contemporary structures and norms are shaping the societal issues that they’re grappling with. We encourage them to listen carefully and with empathy to perspectives and opinions that may be different from their own. We also encourage them to think about how what they learn in the community can inform their academic inquiry, and how insights from research can guide their community engagement. These practices are vital if we want our communities to flourish in more just ways.