The Year of the Tiger that launched with the Lunar New Year on Feb. 1, 2022, has been a moment of pride and reflection for Princeton’s vibrant Asian and Asian American community. Throughout the year, we have elevated the voices of faculty, staff, students and researchers in a series of thoughtful interviews exploring questions of identity, pride, hope, the lived experience of anti-Asian racism, and meaningful steps that allies can take.

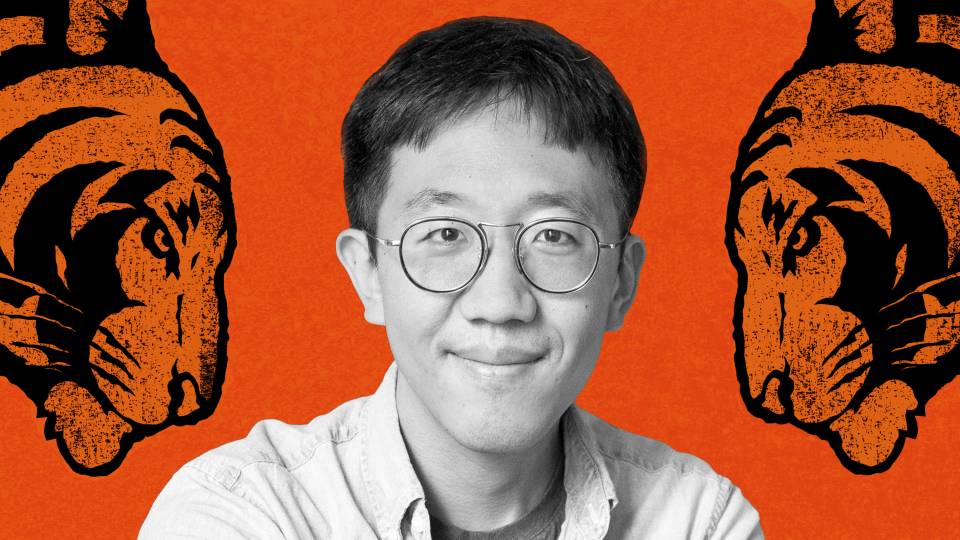

As the Year of the Tiger concludes this month, we share the last installment of our interview series. Ella Gantman, Class of 2023, plays goalie on the women’s varsity soccer team. She is concentrating in the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs and pursuing a certificate in Spanish.

Gantman co-founded The Poll Hero Project, which mobilized more than 37,000 young people to volunteer as poll workers during the 2020 election. On campus, she served as the lead athletics fellow for the Vote100 program, spearheading voting initiatives for nearly 1,000 student-athletes. Gantman grew up in Washington D.C., and spent last summer interning at the Department of Justice’s Office of Civil Rights through the Scholars in the Nation’s Service Initiative.

How do you self-identify?

This has always been a hard question for me, but I will try to unpack it.

Ella Gantman is a four-year varsity athlete on the women's soccer team.

I was born in a rural rice town in Hunan, China, to Chinese parents that I will never know. A week before my first birthday, I was adopted by a white family from the United States. My dad is American and my mom is Argentinian. They are also both Jewish. As such, I identify as Asian American and Latino American and Jewish — all at once.

Growing up, this left me frustrated. I felt like pieces of many things, but never fully anything. Since my mom was born and raised in Argentina, I was raised most closely with that culture. We visited Buenos Aires every year and spoke Spanish at home. I learned to be comfortable identifying as Latina (even if the outside world did not see me that way).

And although both my parents are ethnically Ashkenazi Jews and my grandparents’ first language is Yiddish, my family rarely practiced Judaism. This distanced relationship to my religion made it difficult to claim. I wasn’t Jewish by blood, and I was barely Jewish by practice. Even so, it remains the only thing I have ever known.

As a child, I sought to create a distance between myself and my Chinese heritage. I anglicized my name, my habits and my language, all as a part of a charade to simplify the complexities of my identity. I laughed while my friends used Asians as the punchline of their jokes. I looked for comfort in whiteness; I hid my eyes behind reflective sunglasses, which I believed could hide my almond eyes from view.

My identity has always seemed to be a contradiction: the Chinese girl tutoring Spanish; the Jewish kid that doesn’t believe in God; the “bad” Asian who doesn’t take their shoes off when they walk inside. I have never “made sense.” But Princeton taught me that my intersectional identities are a strength. For the first time in my life, I have met Latinx Asians, Jewish Asians, Jewish Latinos and every other combination, offering me communities that I thought did not exist.

Today, I am still figuring out who I am. I am confident in identifying as Chinese, as American, as Argentinian and as Jewish. Mostly, I am proud to be all of them at once.

What makes you feel proud to be an Asian American?

Gantman, who grew up in Washington, D.C., is a young child in this undated family photo with her mom, Ana Levenson, her dad, Howard Gantman, and her late family dog, Bottito.

I didn’t grow up in a typical Asian American household or community. So there was a long time where I did not feel proud to be Asian American, not because I didn’t support the community, but because I did not feel I could claim it as my own. I felt like a fraud. I have since learned that this feeling is called racial imposter syndrome (when your internal sense of self does not match with others' perceptions of your racial identity).

Ironically, perhaps, having the language for this feeling has empowered me. It showed me that I am not alone. Racial imposter syndrome is a phenomenon shared by many trans-racially adopted kids, which has allowed me to discover the greater Chinese adoptee community. Through the Facebook group China Children International (CCI), I have met other young women who were adopted and share similar experiences as me. The community was one I desperately needed and for the first time validated my experience as an Asian American person. It helped me realize that even though I don’t speak the language or know the nuances of the culture or traditions, I can still be a proud Asian American woman.

What can allies and others do to counter anti-Asian racism?

I think one of the most important misconceptions to address is the fact that anti-Asian hate is not isolated to racist slurs or kids pulling back their eyelids and speaking in a crude accent. It is not even isolated to a demolished storefront or a woman pushed onto train tracks. These events are awful and they should be widely acknowledged, shared and mourned. However, anti-Asian hate — like many systems of oppression in this country — are systemic and their solutions must be too.

Working to counter anti-Asian racism will require all of us, Asian and not, to expand our collective understanding of how race works in this country. I think one actionable way we can do this is by working to unlearn what Mount Holyoke professor Iyko Day calls the “Black-White racial binary" in her book "Alien Capital." In other words, in the United States, our conversations about race position Black and white people on opposing sides of a binary, seldomly considering those who are neither. By limiting ourselves to this binary, we erase the unique experiences of many racial groups.

In the case of Asian Americans, we often overlook how immigration laws in the 1920s, imperial wars abroad in the 1950s and 60s, and ongoing colonial projects in the Pacific Islands (as well as many other events that cannot be contained to a sentence), have and continue to impact Asian Americans today. Moreover, countering Asian American racism will require each of us to unlearn the “perpetual foreigner” and the “model minority” myths, which confine us to a monolithic stereotype and often times rob us of our American identity, and in some cases, even, our humanity. We must educate ourselves on our past and how it informs our present, in order to build a more equal future.

Are there examples from what you’re involved in to counter anti-Asian racism that empower you?

I don’t think that there’s one grand solution. But every person, in their own way, can rewrite society’s understanding of what it means to be Asian American.

I have found empowerment in breaking the stereotypes people hold about me, as an Asian American woman. One that bothered me most growing up was the notion that we are supposed to be quiet, passive and unproblematic. In other words, that Asian women should make themselves small; that we are not born to lead. In freeing myself from this stereotype, I have learned to take command of a room through my voice. I hope that in doing so, I allow future Asian American women to feel comfortable in theirs too.

For me, one of the most important spaces on campus where I have found my voice is in Princeton Athletics. I am a four-year varsity athlete on the women’s soccer team. When I arrived at Princeton in 2019, our team was (and still is) primarily white. In turn, as I looked around the soccer field, I didn’t see anyone who shared my lived experience. Although this felt isolating, it encouraged me to actively work to put racial justice at the center of our team’s values. As a sophomore I founded and chaired our team’s diversity, equity and inclusion committee and facilitated tough discussions through movie viewings and book readings. I also helped form our team’s active partnership with “A Long Talk About the Uncomfortable Truth,” an anti-racism activation experience which we engage with four times a year.

Although I did not play very many minutes throughout my athletic career, I found a leadership role on the team through my voice. Since then, many of our first-years and sophomores have shared with me that feel seen and safe on the team. To me, this is more important than any time spent on the field. Their empowerment is mine. It is also the empowerment of every woman of color who joins our team in years to come.