The Year of the Tiger that launched with this Lunar New Year is a moment of pride and reflection for Princeton’s vibrant Asian and Asian American community. Throughout the year, we are elevating the voices of faculty, staff, students and researchers in a series of thoughtful interviews exploring questions of identity, pride, hope, the lived experience of anti-Asian racism, and meaningful steps that allies can take.

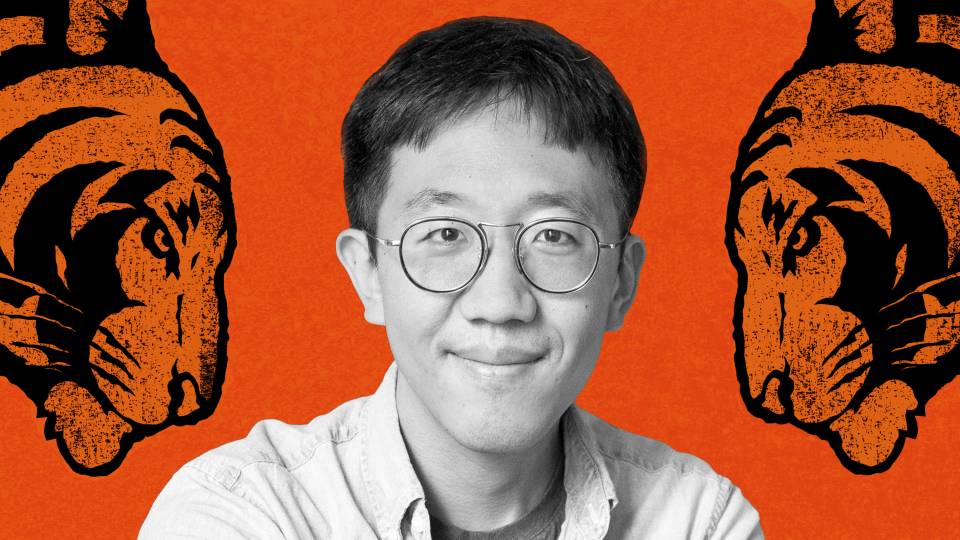

Susan Baek is the creator of the Princeton podcast network "P's in a Pod."

We continue the series with Susan Baek, Class of 2023, who is majoring in the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs and pursuing minors in cognitive science and Asian American studies. Baek, a member of Mathey College, participates in numerous clubs and activities related to her law and public policy interests including Princeton Mock Trial, Princeton Legal Journal, Matriculate, Vote100, American Whig-Cliosophic Society, and Princeton Pre-Law Society. She is also the creator of the Princeton podcast network “P’s in a Pod.”

How do you self-identify?

My answer to this question has changed over the years. Right now, I would say I identify as Asian American. I’m a first-generation and a second-generation Korean American. My mom immigrated to the U.S., shortly before marrying my father. My dad grew up in the United States. I grew up in a home where my mom would cook Korean food three times a day, and my dad showed us Rachel Maddow at night. And so, I was raised with these parallel worlds — and often conflicting worldviews — between my two parents.

That was very informative for my own understanding of the world, and also of myself. Their political ideologies, for sure, came into conflict. It challenged me at a very early age to interrogate motivations behind ideology. For them to come to different conclusions about the world allowed me to question my own teachings at school, my own readings and then my own interpretations of the world around me.

I’ve come to see being Asian American not as something that I was necessarily born into or labeled with at birth. I now see it as a choice of a label, a choice of political action, a choice of identity, a choice of engagement with my identity.

What makes you proud to be an Asian living in America?

What makes me proud to be Asian American is being able to enter spaces with an evolving identity. There’s a history before 1965. But then when the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was enacted, there were waves of immigrants who arrived in the U.S. with different histories that came into conflict with pre-existing histories of the United States. Today, I have Asian peers around me at school who come from different generations of experience, and also from different countries, different mother tongues, different fluid levels of fluency, different stereotypes. And because it’s not a monolith, I’m proud to identify with the term because I know that I bring so many questions to the table. While I might be perceived as one thing, it’s almost impossible to perceive me as what I fully constitute.

There is definitely pride in being able to use my identity to open and broaden spaces on campus that had not existed there previously for the communities to which I belong. When I refounded the Princeton Legal Journal, for instance, I started a guest speaker series to talk about a variety of legal topics. I was often the one inviting the guests, and because I wanted to represent underdiscussed topics, we hosted speakers who are women of color and speakers coming from underrepresented communities talking about the law in ways that many students here probably have not seen.

What can allies and others do to counter anti-Asian American racism?

I’m a big fan of storytelling. But I think there are spaces into which non-Asian individuals don’t have to enter in order for them to be listening. I think it’s allowing people who identify as Asian American to have our own spaces sometimes to discuss our similarities and differences and our pride and joys and our pains without the external gaze. Another thing people can do is to learn the history behind the term Asian American, the debate around the use of the word AAPI or API, Asian American and Pacific Islander, the harms that that term might imply, the diversity in stereotypes that Asian Americans receive — it’s not just the model minority.

I think becoming educated about these terms allows people to engage with the people themselves better and listen better, because when I say I’m an Asian American, I bring to the table a whole horde of anxieties and awarenesses and acres of pride. But if someone listening hears the word Asian American and thinks of the one thing they’ve learned in middle school, then we’re already on different pages about what identity even means.

I would also say for everyone — and this is not just for being an ally — but I think everyone should understand their own history better. I think that everyone has an identity that brings value when it’s connected to other identities. We’re all human, and with being human we all have one identity. Educating ourselves as individuals about the complex history and personal stories behind our identities allows every one of us to be better listeners.

Are there examples from what you’re involved in to counter anti-Asian American racism that empower you?

I’m currently the president of the Princeton Mock Trial program here. It’s an activity that might seem completely unrelated to ethnic, racial or gender identity, but it is very much related to all of the above. There are a lot of times when members of the community feel at risk of harm or offended or unsafe because of someone else’s views or someone else’s actions. It has taken four years of being a part of the club to even begin to understand the best course of action whenever that happens.

A way to bring those issues to the attention of people who might not recognize that they exist is by bringing people together on other things, whether that’s creating bonding activities that have nothing to do with mock trial or having political debates where we hash out our opinions on a very controversial political issue. We started hosting game nights, we also started a big-little program. Then on van rides to tournaments, we started traditions, like there’s one song game that we play that I really love where everyone shares a song and its importance to them.

I really wanted to drill into this program that we’re a community first, and a competitive activity second. We are creating these small spaces where people have to empathize and listen.

I think that builds these webs of understanding and belonging that make it a lot more difficult for people to look down on other people or undermine anyone’s humanity because everyone just gets to get to know each other better. And maybe they don’t like each other, but they recognize the dimensions that everyone has. Racism will always exist. And at its core, it exists because we’re not confronted with the humanity of other people. I think making that happen is a difficult task, but it must be done.