The Year of the Tiger that launched with this Lunar New Year is a moment of pride and reflection for Princeton’s vibrant Asian and Asian American community. Throughout the year, we are elevating the voices of faculty, staff, students, alumni and researchers in a series of thoughtful interviews exploring questions of identity, pride, hope, the lived experience of anti-Asian racism and meaningful steps that allies can take.

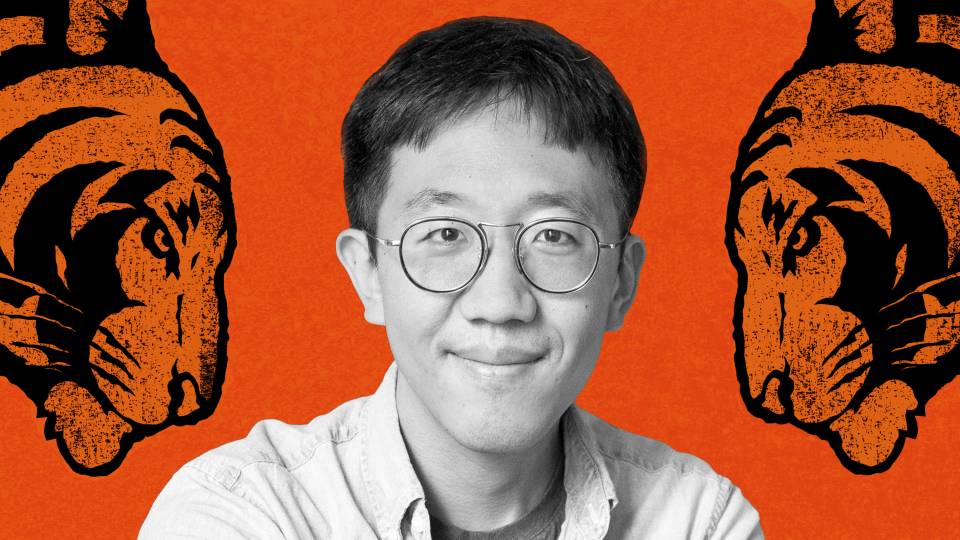

Angel Velasco Shaw

Angel Velasco Shaw, a lecturer in Princeton’s Effron Center for the Study of America, is a visual and media artist, educator and curator living in New York and Manila, with works in many museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Manila, Cinematheque Suisse Schweizer Filmarchiv in Switzerland, Casa Asia in Spain, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

How do you self identify?

That’s a tricky question, especially for someone who grew up in an interracial and interreligious Filipino-Jewish household in the Bronx and Chappaqua, New York, in the 1970s during a time when there were not a lot of interracial and interreligious families around. My mother was a pediatrician working in the service of the urban poor and my stepfather was a music producer. Many of our neighbors were critical of the “atypical” way that we were being raised.

My internalization of feeling like I was not part of the American “norm” caused an unease that haunted me until my early 20s, when I became acutely aware of our difference, a difference that I embraced with dignity despite being bullied for years by my classmates.

Context is really important. Sometimes my response is “Asian American,” “Filipina/x,” “American,” “a human being” or I don’t respond at all. It depends on the situation I am in, who is asking an identity question and the tone of the person that is asking. There are so many variables that influence how a person identifies — one’s upbringing, education, life experiences, self-confidence, involvement in pan-Asian American or ethnic-specific Asian American communities, etcetera. For bi-racial and multi-racial people like my sister, niece and nephew, how they identify is a whole other series of complex negotiations.

Ironically, I feel like I’m a little too old to keep addressing this question. Nonetheless, as tired as I am of the “tyranny-of-appearances,” I will continue to name myself. This deliberate action continues to be a source of empowerment and agency.

What makes you proud to be Asian American?

Our histories in the United States. As Asian/Southeast Asian/Sub-continent and Pacific Islander Americans, we contributed to the building of this nation, fought for this nation in times of war, and continue to work hard for the health of this nation as law-abiding citizens and residents living here.

Knowing about the history of the pan-Asian American movement that began in the late 1960s makes me proud to be an Asian American. It was a time of convergences, when college-age Americans of Asian descent joined in solidarity with those active in the Black Power, civil rights, Latin and Native American, anti-war, gay and lesbian, Third World liberation, and women’s movements. Today’s movements such as Black Lives Matter, Indigenous people’s rights, anti-Asian violence, #MeToo, pro-choice, transgender and climate are part of this continuum.

Discovering my history as a dual citizen of the U.S. and the Philippines made me question what being an American meant. When I graduated from art school in the mid-1980s, I went on this labyrinthine roots-to-routes journey that impacted every aspect of my being.

My sense of transnational pride stems from hearing family war stories like the one about my great-grandfather being exiled in Hong Kong with President Aguinaldo during the Philippine Revolution against Spain, and the one about my paternal grandfather being tortured and imprisoned by the Japanese for being caught with a short-wave radio — and then three years into the war, escaping from a penal colony that was 1,500 kilometers away from Manila. But it was the story about how my father as a 7- to-10-year-old boy took care of his family during those long war years, and about my mother running away from the Japanese when they were retreating at the end of the war, that enabled me to fully understand where my resilience came from. There are so many, many stories — these acts of resistance influenced my body of work focusing on the Philippine-American War, empire-building and decolonization, among other related topics.

Mainstream society, including Asian Americans, use the term “Asian American” without really knowing the genesis of the term. Despite the fact that Asians, actually Filipinos, have been living on North American soil since 1763, we remain perpetual foreigners, other, alien. We continue to have to prove our citizenship, loyalty and Americanness. The Asian American movement is, in fact, what binds us together. We are so, so diverse. Being able to create, teach, learn and live these realities on a daily basis is what makes me proud to be Asian/American.

What can allies and others do to combat anti-Asian racism?

Combatting anti-Asian racism is a long and arduous battle. Physical and verbal violence against Asians have been happening ever since our arrival in this country over 200 years ago.

This is a good place in the interview to share a story about a fairly recent incident that occurred a week after my return to New York after living in the Philippines for eight years. I was walking down Riverside Park on the Upper West Side. And this young white woman looked me straight in the eyes and said, “Get the [expletive] out of here.” I was so stunned that I didn’t quite know what to say. Finally, I asked, “Well, where are you from? Is this necessary?”

I don’t know if this woman could ever be an ally. But I definitely don’t want to rule her out, either. Before this encounter, I’d never been afraid of walking around New York City. I’ve been racially slurred before, but this felt different. It felt like hatred. And that’s painful.

Combatting such behavior requires broadening our communities of allies through more integrated academic courses and workshops for all ages, steady support for Asian American culture and the arts, cultural immersion in diverse communities to engage with each other in non-didactic ways, and grassroots initiatives that embrace difference, not fear it. What I am suggesting is not new, hardly. Generations of Asian Americans, other marginalized peoples — kindred spirits — from all walks of life have been doing this hard work for decades. What I am suggesting is interlinking with a continuum that many people, including Asian Americans, do not even know exists.

Are there examples from what you’re involved in to counter anti-Asian racism that you think would help others?

Over the course of my life, I have come to understand how all of these histories that I’ve touched upon live within me as a storyteller, image maker and educator. Perhaps this is one of the main reasons why, in my own humble way, I have dedicated my life to combatting all forms of prejudices and injustices.

Besides my visual and media art practice, curatorial and multidisciplinary cross-cultural exchange projects that I produce, I try to interact with as many everyday people as much possible as a deracializing gesture. I smile and say hello to total strangers, ask them how their day went, or help them in some small way if they need it. I also worked in the nonprofit cultural sector with organizations whose mandate it is to produce projects that promote Asian American visibility.

I have been teaching Asian American Studies in this country for 22 years. I was first asked to teach an Asian American Studies course at Hunter College in 1993. Simultaneously, I was starting to get recognition for my film and video work. Coming out of a conceptual art school and being a practicing artist, I had no idea what Asian American Studies was. The professor who hired me at Hunter told me “just teach about your life.” I am simplifying things, but my passion for teaching really grew out of these early encounters with largely Asian American youth.

In my classes over the years and now at Princeton, I’ve brought in a variety of guest speakers — some who were part of the early movement when they were the same age as the students are now. I invited these specific artists, filmmakers, writers and educators because I knew their “talk-story” interactions would be inspiring on multiple levels. Countering anti-Asian racism is all about creating openings — spaces in which we use our skill sets, tools, life experiences to build these bridges between and across our histories, cultures and young people. That’s how we can participate in shaping a more just future.