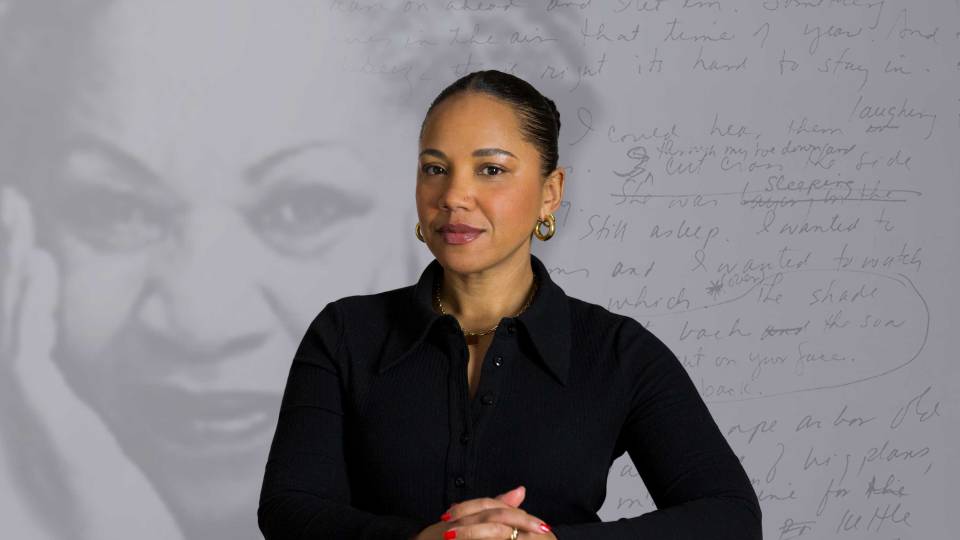

Students in the course “Poetry and War” explored the work of French poet René Char — who continued to write through World War II as a member of the French Resistance — with visits to the Réne Char Papers, held in Princeton University Library’s Special Collections, a spring break trip to France and a public reading of the students’ own translations. Pictured: Sandra Bermann, the Cotsen Professor in the Humanities and professor of comparative literature (far right) works with students in the archive.

When poet René Char joined the French Resistance against Nazi occupation of France in WWII, he led sections of the maquis, rural guerrilla units, in Provence, and orchestrated dangerous parachute landings of arms and munitions — all the while continuing to write poetry. After the war, in 1946, Albert Camus first published Char’s “Feuillets d'Hypnos” ("Leaves of Hypnos"), a “notebook” of 237 prose poems reflecting on the conflict but also on humanity, nature, freedom and hope.

This spring, students in the course “Poetry and War: Translating the Untranslatable” explored Char’s poetry in its historical context and its ongoing "afterlife" in translations around the globe. They explored the Char Papers, held in Princeton University Library’s (PUL) Special Collections. On a spring break trip to France, they met Char’s widow and editor, Marie-Claude Char, who guided them on a literary and historical journey exploring her husband as poet and Resistance leader. Back on campus, their work culminated in a dramatic public reading of the "notebook" in multiple languages, using the students’ own individual translations.

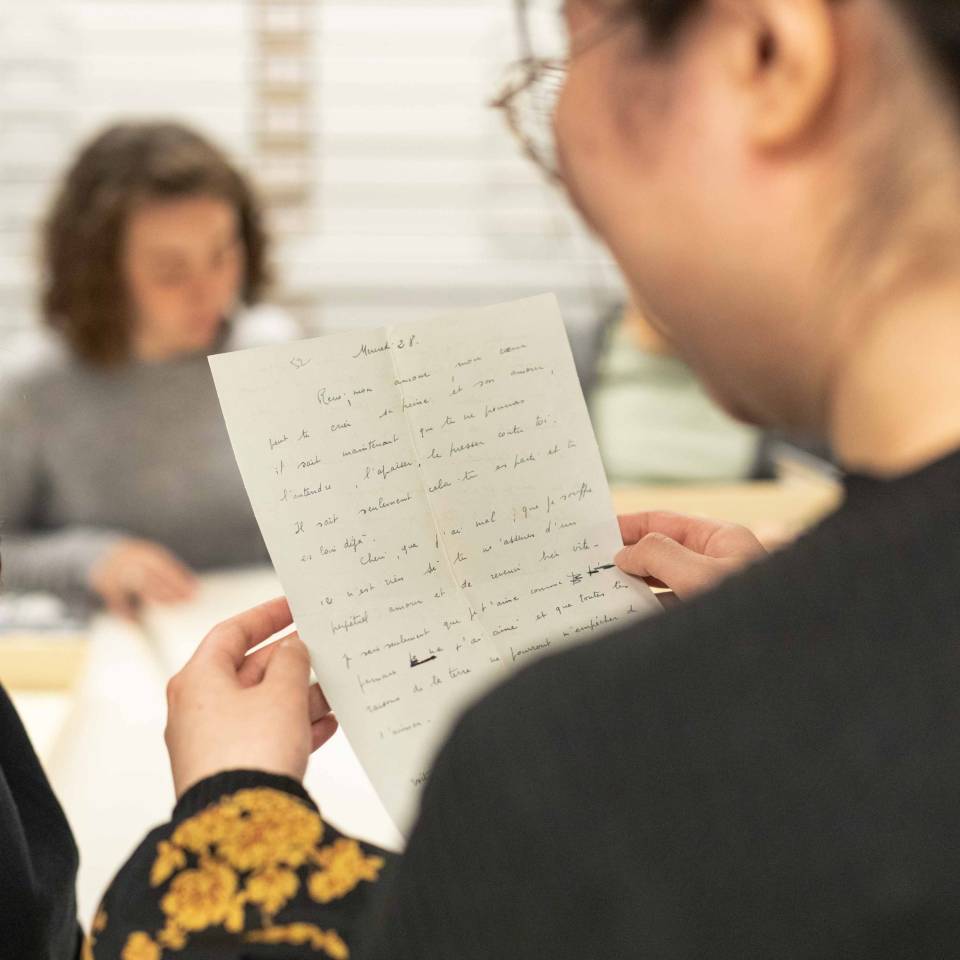

Students engage in archival research with the René Char Papers at Princeton University Library. Pictured (left to right): Pippa LaMacchia '26; Jennifer Garcon, librarian for Modern and Contemporary Special Collections; Sandra Chen '24; and Kate Short '23.

“Char’s poetry is powerful,” said Sandra Bermann, the Cotsen Professor in the Humanities and professor of comparative literature. “It engages deeply with human suffering, but also with the solace offered by dialogue, attentiveness to the people and things around us, and by poetry itself. Though its language is not always easy, changing registers throughout from the practical, to the lyrical, to the philosophical, his texts have been translated into more than 30 languages and have influenced writers and artists around the globe.”

Bermann developed the course to dovetail with a book she is now writing on Char’s war-time poetry. It also connects closely with an international translation project she is leading, the Char Translation Project. Bermann is collaborating on this with Jernej Habjan and Fabrice Langrognet, two former Fung Global Fellows — a PIIRS program that invites five international scholars to Princeton for one academic year to research, write and collaborate around a common topic; Bermann served as faculty director in 2020-21. The course and the Char Translation Project are supported by the Humanities Council Magic Project, which encourages innovation in the humanities and works with faculty to develop experiential learning opportunities for students.

Bermann began reading Char’s work as a graduate student at Columbia; her fascination with his writing deepened after she joined the Princeton faculty and sat in on a course being taught by a visiting professor, Mary Ann Caws, one of Char’s early and best-known translators.

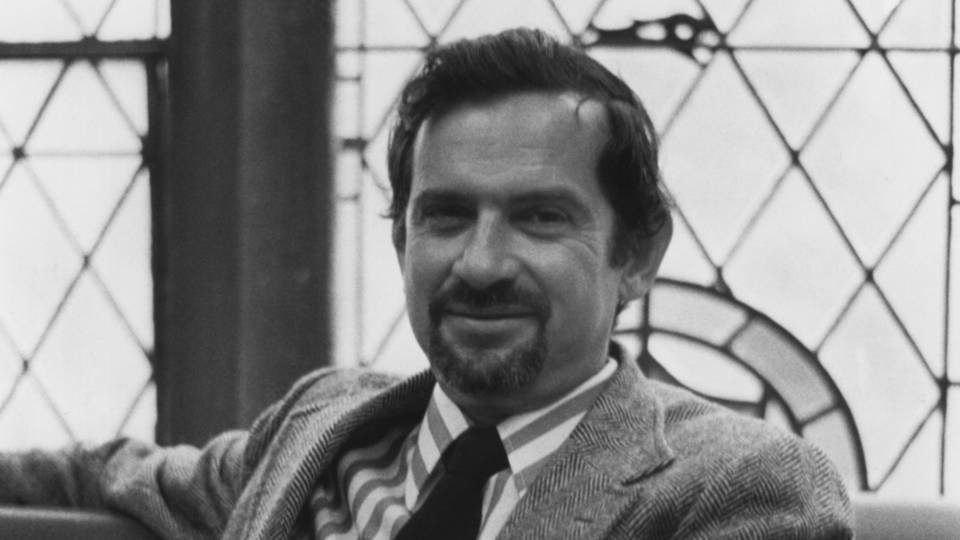

A poet with the code name ‘Capitaine Alexandre’

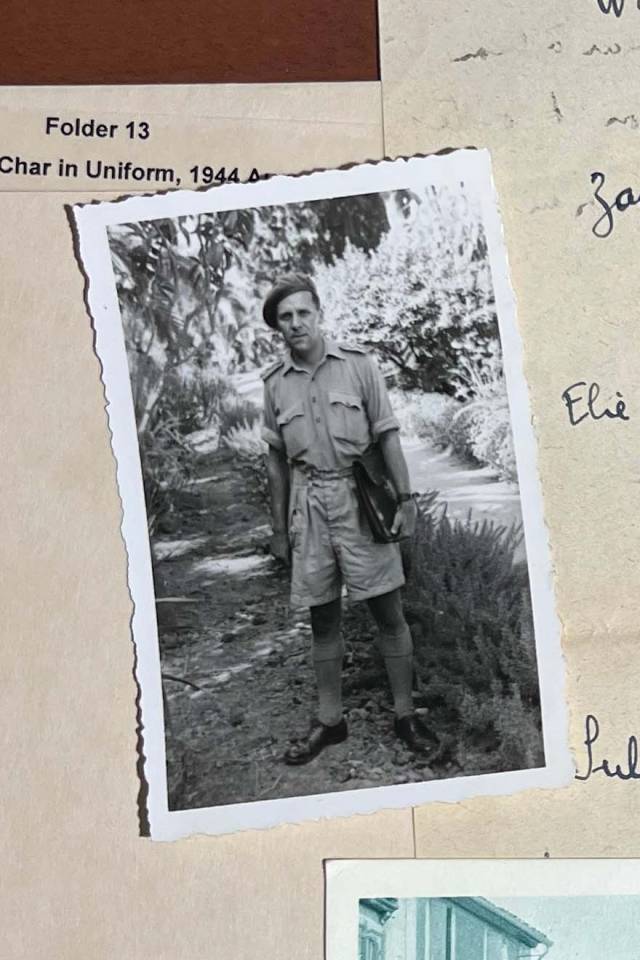

A photo of René Char from the archive.

Char was born in 1907 in Isle sur la Sorgue, a town in Provence, France. By 1930 he was associated with the surrealist movement in Paris but left the group in the mid-1930s and “a new poetic voice began to emerge, one more directly engaged with issues of political as well as poetic freedom,” Bermann said.

Soon after France declared war in 1939, Char was mobilized in Nimes and fought in the battle of Alsace, in the 173rd regiment of heavy artillery. Demobilized in 1940, he returned home, but only briefly; he was soon denounced there as a militant of the extreme left. Thanks to a timely warning, Bermann said, Char escaped with his Jewish wife, migrating to the remote village of Céreste, where he had friends and could settle safely.

By 1941, Char began to connect with Resistants in the area, organizing against Nazi occupation of France. In 1942 he joined the Armée Secrete (AS), acting as head of the section Durance-Sud under the code name of Capitaine Alexandre, a name he kept until the end of the war. By 1943, he was leading partisan groups of the Forces Francaises Combattantes (FFC) in Provence and served as departmental chief of seven regions of the Maquis for parachute landings of arms and munitions in the Basses Alpes. In July 1944, Char was called to Algiers to advise the Allied Headquarters as a liaison officer in preparation for the landing operations in the Mediterranean.

Unlike other French Resistance poets, Char deliberately chose not to publish any of his work between 1941 and the end of the war. “He was skeptical about the political and personal motives of most ‘Resistance poetry’ and decided to wait till the war was over — and won — before publishing his work,” Bermann said.

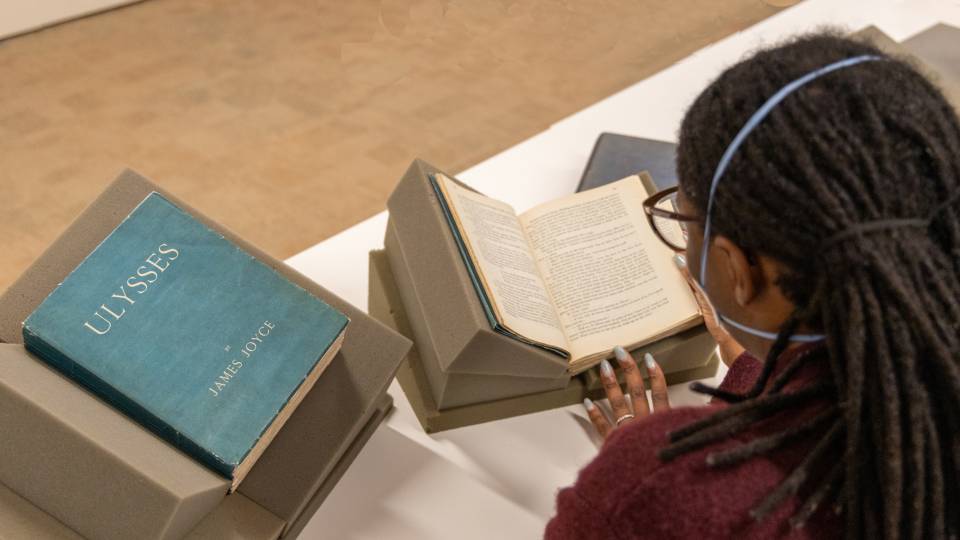

In the archives: Poetry, parachute maps and paper remnants

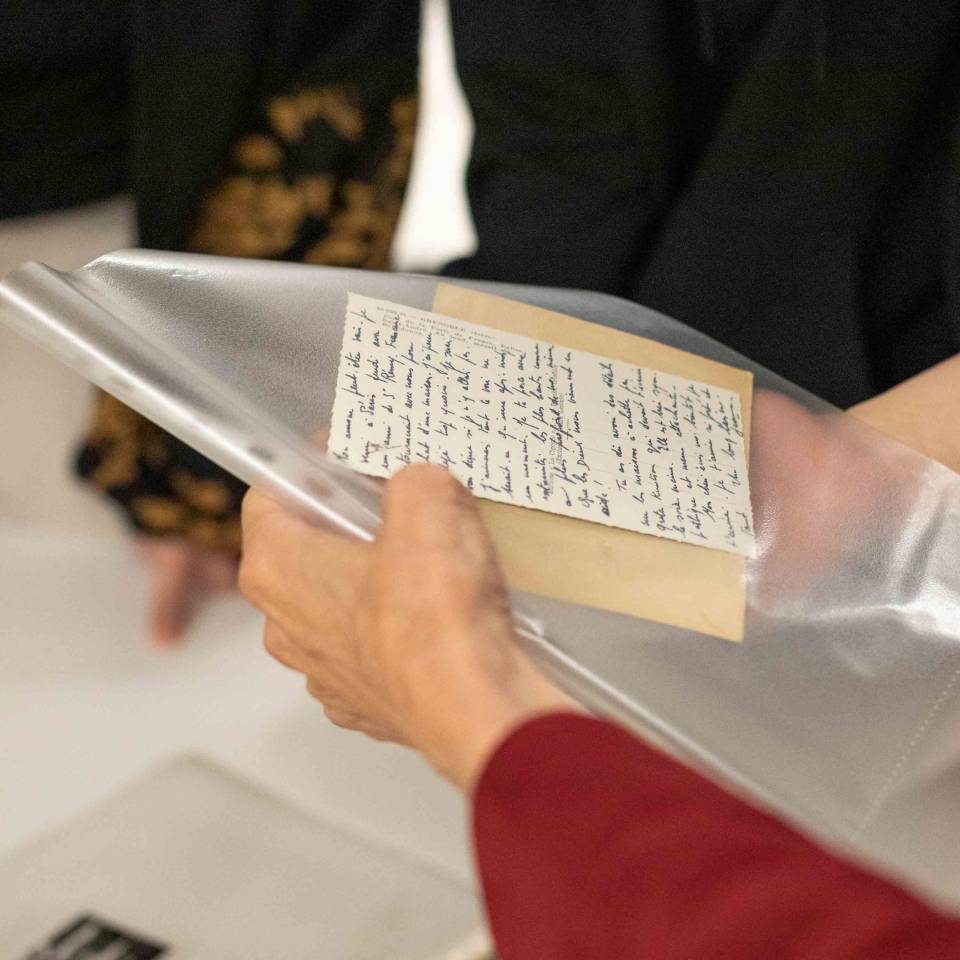

In PUL’s Special Collections, Bermann and her students spent time searching through boxes of the Char Papers. Split into two series — papers related to the Resistance movement, and the correspondence Char had with friends and family — items include maps, letters, handwritten documents, telegrams, postcards from companions in the Resistance often written under their noms de guerre, photos and ephemera from hotels and cafes. The correspondence series includes letters received by Char from other authors, journalists and artists, including Albert Camus and Pablo Picasso.

“You get a sense of the materiality of the times,” said Jennifer Garcon, librarian for Modern and Contemporary Special Collections. “Paper became quite scarce. People were grabbing and using paper wherever they could.”

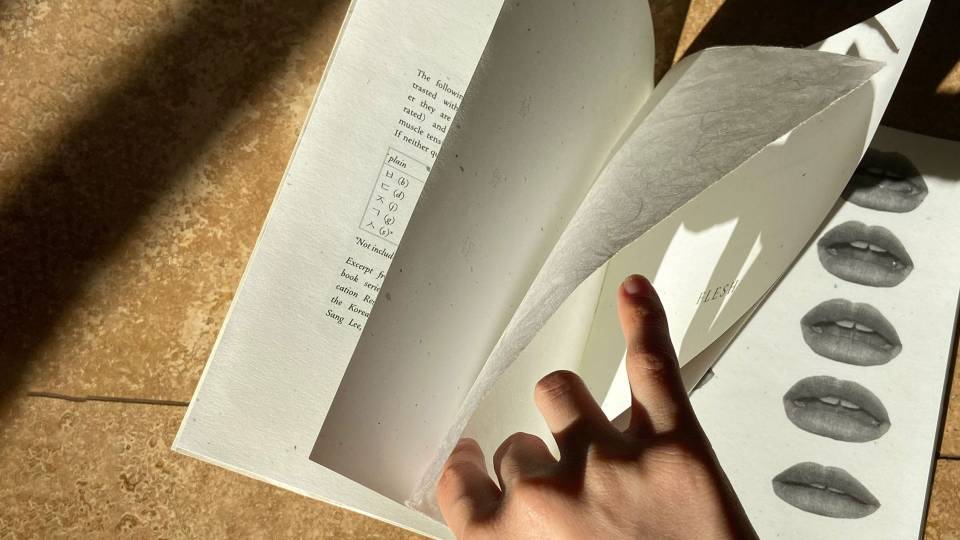

The Réne Char Papers contain maps, letters, handwritten documents, telegrams, postcards from companions in the Resistance, photos and ephemera from hotels and cafes.

Sandra Chen '25 examines an item from the archive. The correspondence series includes letters received by Char from other authors, journalists and artists, including Albert Camus and Pablo Picasso.

As part of the French Resistance, Char commanded the Durance parachute drop zone. Students saw some of the maps documenting the parachute locations in the Basse-Alpes (now called the Alpes de Haute-Provence), coordinates for the parachute and landing grounds, and reports, letters and documents about the parachute teams.

“Within the papers, students discovered ciphers used by Resistance fighters to decode landing sites and times in order to replenish their resources and supplies to continue their fight while also evading discovery,” Garcon said.

Sam Himmelfarb, a member of the Class of 2023 and an English major, was drawn to the correspondence between Char and Artur Międzyrzecki, his Polish translator. “You get a sense of the spirit of friendship and admiration that Char inspired in his collaborators,” he said.

Read more about the Char Papers in a PUL blog post online.

In France: Tracing Char’s life from Paris to Provence

During the week of spring break, Bermann and her class visited Paris and Provence to gain deeper knowledge of Char’s life and poetry.

There they met Marie-Claude Char, who paved the way for a number of special opportunities, visiting libraries, art museums and sites related to Char’s role in the Resistance, including his home in Isle-sur-la-Sorgue and his wartime headquarters in the remote village of Céreste.

During a spring break trip to France, the group stops in front of the “Place René Char” street sign in central Paris. It reads ‘Place René Char (1907-1988): Poète et Résistant” and was dedicated in 2007 at the centenary of Char’s birth. Leading the group are: Sandra Bermann, the Cotsen Professor in the Humanities and professor of comparative literature (fourth from right); Marie-Claude Char (third from right); and Florent Masse, senior lecturer in French (second from right).

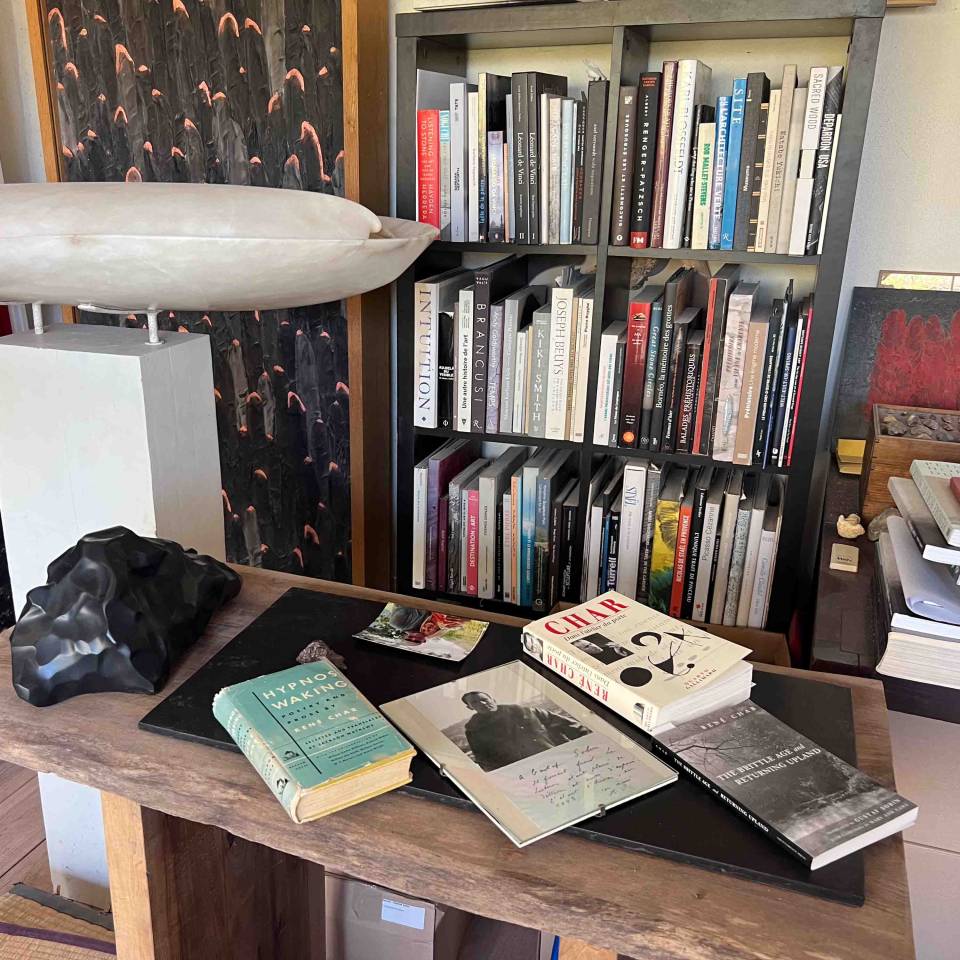

At the home of Gabriel Sobin, a contemporary sculptor inspired by René Char, a table displays translations of Char by his father, Gustaf Sobin; Jackson Matthews; and Mary Ann Caws and Nancy Kline (with an introduction by Sandra Bermann).

On the fireplace mantel in Char's office in his home in Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, photos and memorabilia are displayed, including artwork created by friends and by Char himself.

At the Bibliotheque nationale de France in Paris, Mme. Char arranged for the students to view Char’s poetry manuscripts stunningly “illuminated” by well-known artists of his time such as Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti and Wilfredo Lam. These items, reminiscent of medieval illuminated manuscripts, are not available digitally.

“The texts themselves were beautiful, but the responses that each artist had to Char's poetry were widely varied, some more restrained and others not,” said Paul-Louis Biondi, a rising senior who is majoring in comparative literature.

In addition to Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, the students visited Fontaine de Vaucluse, the nearby town and source of the Sorgue river that frequently appears in Char's poetry (as well as in that of Francesco Petrarca centuries before), and met with a contemporary sculptor deeply influenced by the poet.

“We sought out places and sights that Char writes about in his poems and that we’d read in class,” Bermann said. She and Marie-Claude Char, along with graduate assistant Peter Makhlouf, created a booklet of poems for the students to bring on the trip, so that the poems and places could be easily matched. “Marie-Claude also answered countless questions that we posed throughout this great adventure.”

Traveling with the group were Rebecca Graves-Bayazitoglu, senior associate dean, Office of International Programs, who holds a Ph.D. in French literature and offered her insights and cultural expertise, and Florent Masse, senior lecturer in French, who grew up in Lille, France, and has served as director of the L’Avant-Scène French theater troupe at Princeton for more than a decade. In Avignon in the south of France, home of the Avignon Theater Festival, which Char co-founded in 1947, Masse led the group on a tour, offering historical insights and a lively sense of the Avignon Festival today.

Bringing Char’s translations to life

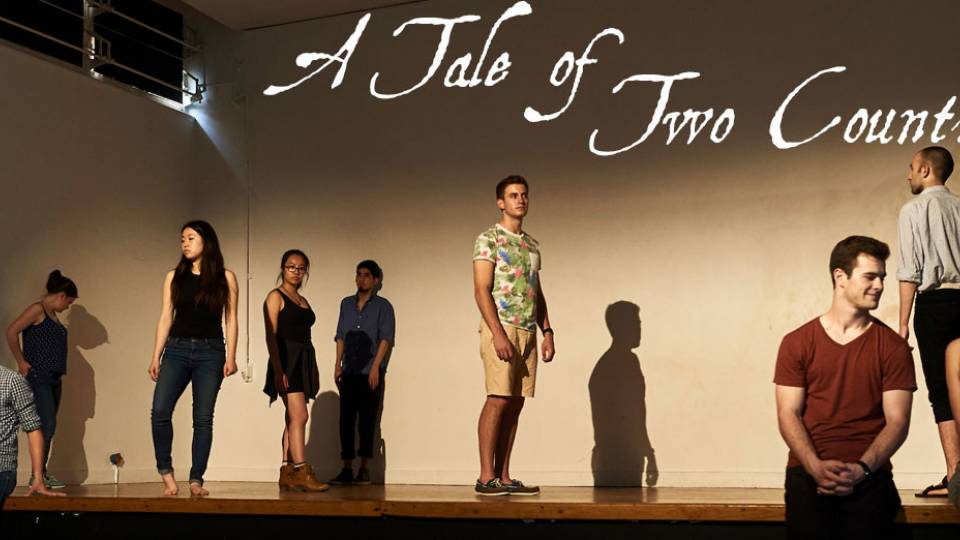

Equipped with the experience of seeing Char’s work at home and abroad, students began preparing for a presentation of excerpts of Char’s “Feuillets d’Hypnos,” translated into a language of their choosing, including Kinyarwanda, Korean, and also a musical composition. They workshopped their translations with Neil Blackadder, professional specialist and translator-in-residence with Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies (PIIRS), and prepared the dramatic event directed by Masse.

Marie-Claude Char came to Princeton May 3-4, helping the students rehearse their translations and reading the French original during the public presentation, held in Chancellor Green Rotunda.

Lana Gaige — a rising senior and comparative literature major who is also pursuing a certificate in humanistic studies and is a member of L’Avant-Scène — translated one of the passages from the collection that connects the reader directly and dramatically to the historical moment. It is a text that offers tactical advice to “LS” (identified with name and alias in a footnote) and signed by “Hypnos.” Placed among the collection’s short prose poems, lyric fragments and aphorisms, the poet’s voice here seems to deliver an actual wartime communication. Below is an excerpt from Gaige’s translation:

Outside the network, no communication. Shut down bragging. Corroborate any intelligence with two sources. Bear in mind fifty percent fictional in most cases. Teach your men to pay attention, to report exactly, to work out the arithmetic of situations. Round up rumors and synthesize.

“The public reading was a moving event, marked by differences in languages and personality — all opening and expanding upon a powerful and complex central text,” Bermann said.

Bermann is already planning for future opportunities to share Char’s work. In addition to her book, she is organizing a conference tentatively scheduled for spring 2024, which will allow scholars and graduate students working on the Char Translation Project to share their initial findings.

“We will be considering the translators’ different political and historical situations as we compare specific poems from the larger collection of ‘Feuillets d’Hypnos’ and experiment with digital analyses,” Bermann said. “We eventually plan to publish this research as an edited book, and the conference will be an important step in shaping that final project.”