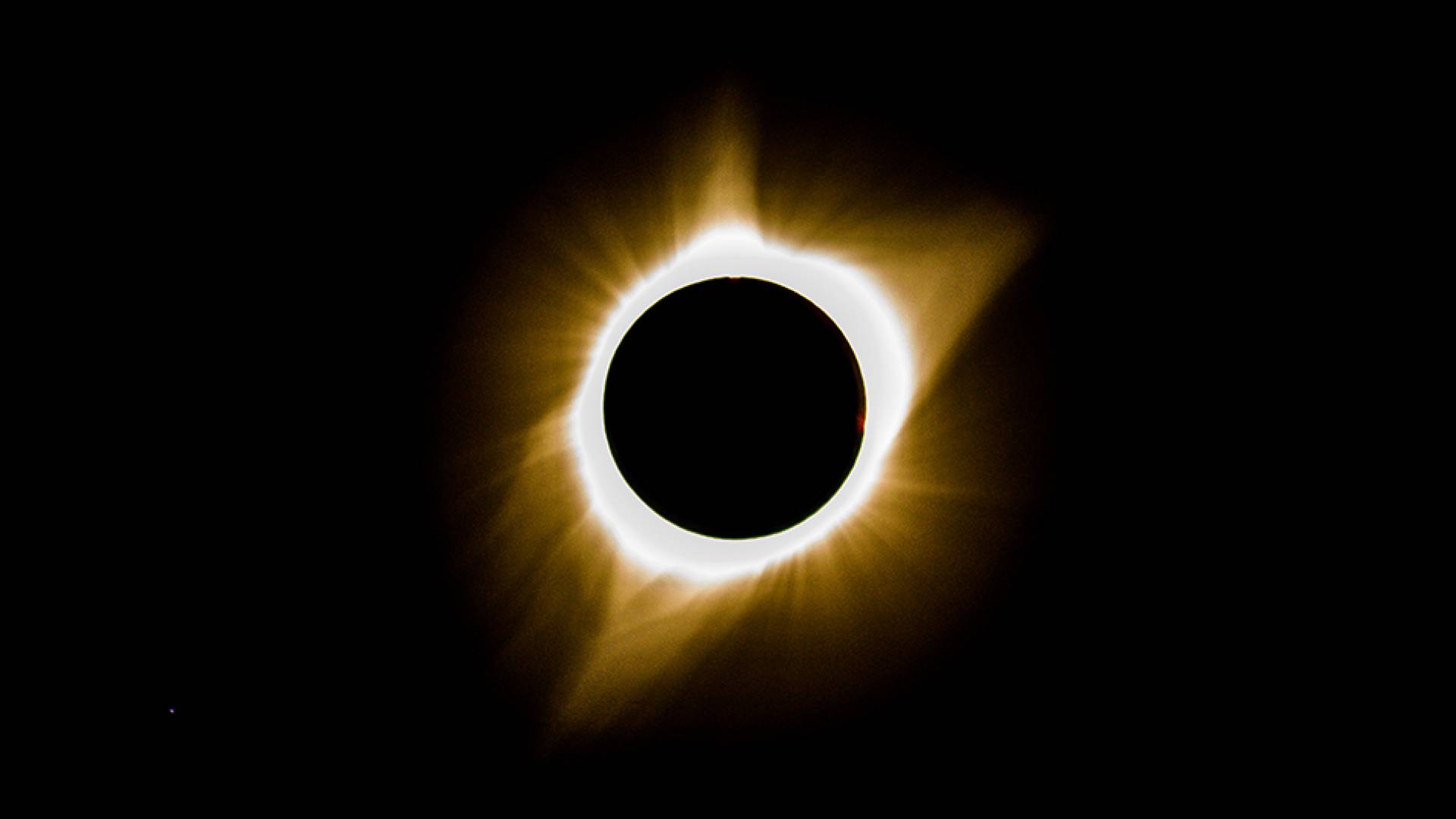

The total phase of the Aug. 21, 2017, total solar eclipse as seen from Casper, Wyoming.

On Monday, April 8, the moon will pass between the Earth and the sun for about four hours. For a few precious minutes, the moon will completely block our view of our favorite star for people in the “path of totality.” Here in New Jersey, just outside that path, the eclipse will begin at 2:09 p.m., reach 90% of totality at 3:24 p.m., and end at 4:35 p.m.

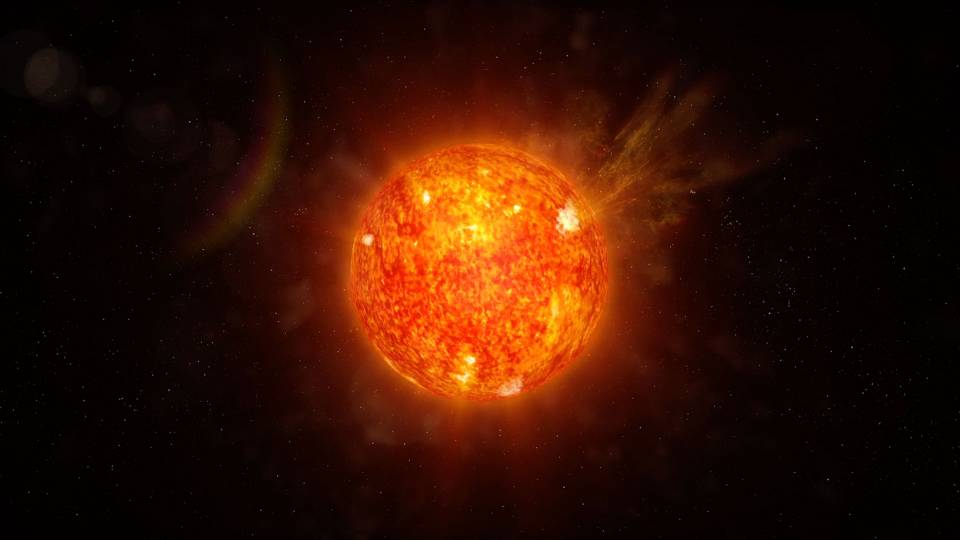

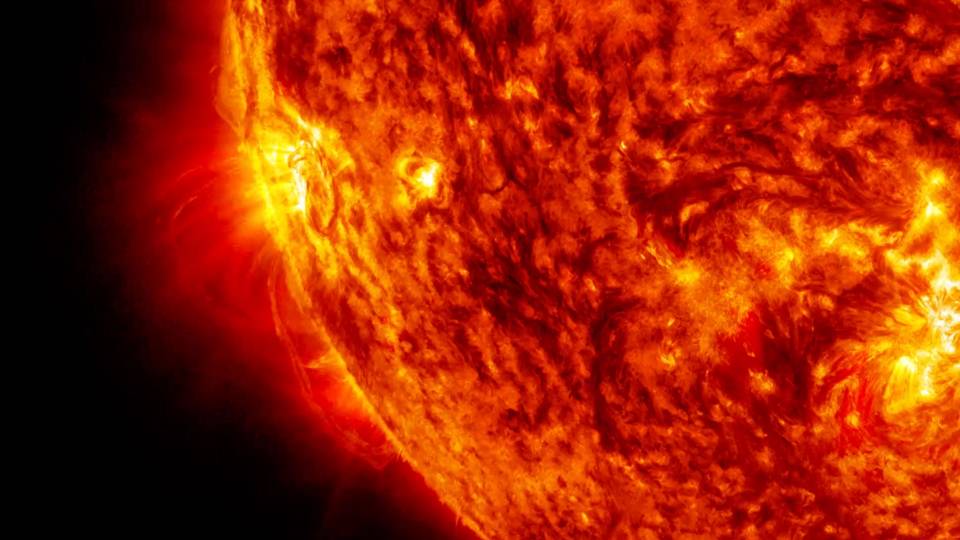

Observers lucky enough — or determined enough — to be in the path of totality will have the rarest view on Earth: the sun’s corona, including plasma tendrils streaming outwards. And because we are near the maximum point of the sun’s 11-year solar activity cycle, the corona should put on quite a show on April 8. The 2017 total eclipse, by contrast, took place near the solar minimum, so eclipse-watchers saw little activity around the sun.

“Because we’re in a period of high solar activity, everyone in the path of totality has a chance to see beautiful loops and streams of plasma coming off of the sun,” said Jo Dunkley, Princeton’s Joseph Henry Professor of Physics and Astrophysical Sciences.

“We often think of the sun as a smooth ball, but if you look at it closely, it’s not like that at all. It’s not solid, it’s a whirling maelstrom of plasma,” she said. “During an eclipse, you get to see the loops and streams of stuff swirling off of the sun.”

Some 30 million Americans live within the path of totality, and more than 200 million live within a few hours’ drive. When equipped with eclipse viewers, they can safely watch the moon’s journey across the sun’s face and see the slowly swirling corona.

A peek from Earth at the ‘solar wind’

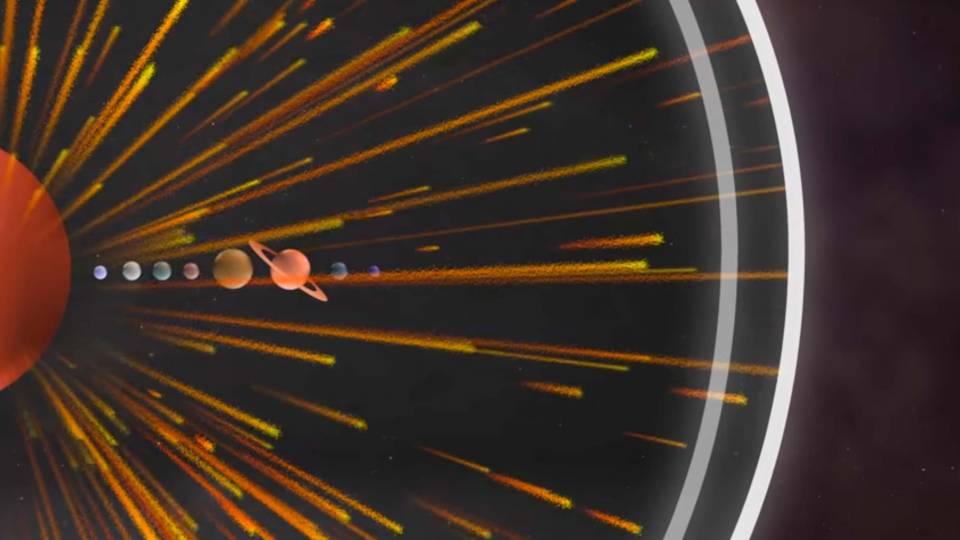

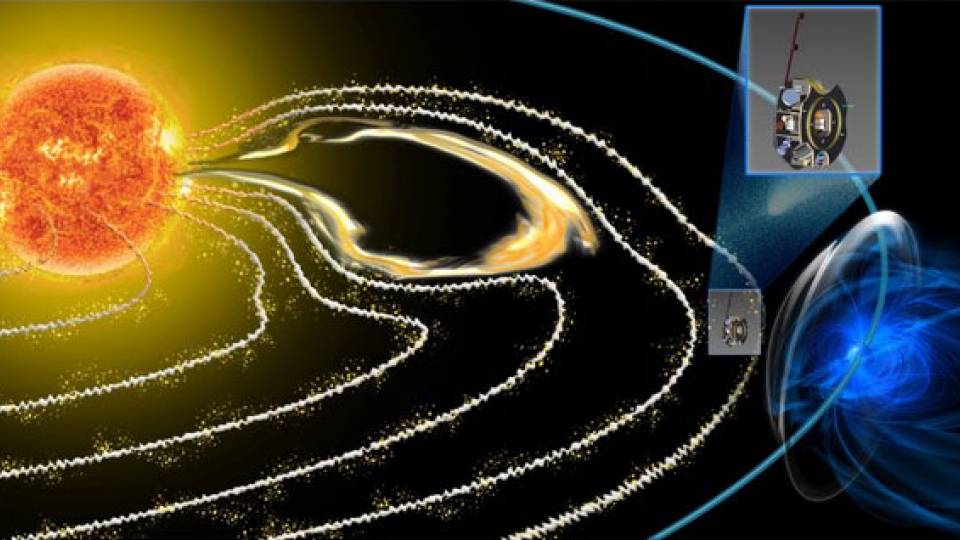

“All the particles and flares and plasma that you can glimpse during an eclipse — those are all part of the ‘solar wind,’ the constant stream of material pouring outward from the sun in all directions,” said Jamey Szalay, a research scholar in astrophysical sciences at Princeton.

“Usually, humans can only see effects of the solar wind if we’re lucky enough to see the Northern or Southern Lights, which are a visible expression of the solar wind interacting with Earth’s magnetic field.”

Szalay is part of Princeton’s space physics group, the branch of astrophysics devoted to studying the sun and everything streaming out from it, also known as the heliosphere.

NASA’s IMAP: a bigger peek in store

The heliosphere envelops the planets, asteroids and the solar system’s other well-known objects, said Jamie Rankin, an associate research scholar and lecturer in astrophysical sciences at Princeton who is another member of the space physics group. “You can think of its outer edge, where all that material streaming out from the sun collides with the interstellar medium, as a galactic shield protecting our solar system from the radiation of interstellar space.”

“The solar wind we see coming off the sun during the solar eclipse in this solar maximum period will impact the entire solar system — all the way out to its boundary with the interstellar medium,” said David McComas, the leader of the space physics group.

McComas is a professor of astrophysical sciences, the vice president for the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, and the principal investigator for IMAP, NASA’s $750 million-dollar Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe mission that is scheduled to launch in about a year to study the heliosphere and its interstellar interaction — one of a fleet of NASA missions studying the effects of solar activity throughout the solar system.

“We’re living in an extraordinary time, learning more about the sun, its corona and the heliosphere than previous generations could have dreamed of,” said McComas. “We have an incredible array of instruments to help us understand our solar neighborhood.”

Watch with the astrophysicists at Palmer Square

In and around the University, Princeton students and community members are collecting viewers and preparing eclipse-watching parties. In Palmer Square, campus groups will provide thousands of eclipse viewers, and experts from Princeton’s Department of Astrophysical Sciences will give talks and answer questions.

Einstein and the path of totality

Observers on campus will see 90% of the sun’s disk hidden by the moon, but that is not enough to glimpse the corona. A few people, like astrophysics graduate student Josef Zimmerman, are traveling to the path of totality.

Zimmerman is hoping to reproduce the experiment performed during a 1919 solar eclipse that confirmed Albert Einstein’s then-four-year-old theory of general relativity.

“Taking a moment to appreciate the awe and beauty of a solar eclipse, seeing the corona with our own eyes, helps us pause from the hectic and stressful schedule of building a complex cutting-edge science mission and reflect on the incredible opportunity we have to be able to study our closest star,” said McComas.