Zia Mian has embraced the role of citizen scientist since he began pondering nuclear disarmament issues more than two decades ago. A research scientist with the Program on Science and Global Security in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Mian uses his training as a physicist to inform international policymakers, government officials and the general public about the dangers of nuclear weapons.

"It's the combination of being a serious scientist and taking seriously your responsibility to be active in your community," Mian, who also is a lecturer in the Wilson School, said of his approach. "It's the role of scholars to help people understand an issue as fundamental as what it means for a country to have nuclear weapons and the capacity for mass destruction that these weapons represent."

In addition to conducting research and teaching at Princeton and engaging with policymakers, Mian writes and offers commentary on nuclear issues in the international press and has produced documentaries to help illuminate the subject. Professor of Public and International Affairs Frank von Hippel, former director of the Program on Science and Global Security, said Mian exemplifies the University's informal motto of "Princeton in the nation's service and in the service of all nations."

"Dr. Mian is what I call an 'activist analyst.' He is interested in research not for its own sake but as a means to help make the world a better place," said von Hippel, who is still involved with the program's research.

Mian also directs the program's Project on Peace and Security in South Asia. His research focus on his native country of Pakistan, its nuclear weapons program and arms race with India, has garnered increasing attention.

"These are two countries armed with nuclear weapons, with very large armies and a history of fighting wars with each other," he said.

The potential dangers of Pakistan and India's nuclear programs, including the fear of terrorists obtaining nuclear materials, underscore concerns about problems in the region and their effect on international security. Pakistan's role as an ally in the U.S. war on terrorism has made it especially important.

"After Sept. 11, many issues combined to bring South Asia into the center of world debate in ways it hasn't been in the past, including the U.S. war against al-Qaida and the Taliban, Pakistan's role in nuclear proliferation and the rise of Islamic militancy there, as well as growing U.S. economic and strategic interests in India," Mian said.

South Asia project

Mian came to Princeton in 1997 as a visiting researcher with what was then the Program on Nuclear Policy Alternatives of the Center for Energy and Environmental Studies. The program was established in 1975 to provide the technical basis for policy initiatives in nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation. In 2001, it became part of the Wilson School as the Program on Science and Global Security.

"The researchers here start from the presumption that you want to reduce the risks of nuclear war and the effects of producing nuclear weapons -- that the world would be a better place if nobody had nuclear weapons," Mian said. "We try to promote ideas that will take the process in that direction."

Mian was recruited to join the program, in part, to work for the Project on Peace and Security in South Asia -- established a year before India and Pakistan carried out nuclear tests in 1998. Among other issues, project researchers have analyzed the effects of a limited nuclear war in the region, the consequences of a nuclear weapons accident and ways to limit the India-Pakistan arms race.

Some of the project's most significant research is conducted through a unique program in which physicists from Pakistan and India spend the summer at Princeton exploring nuclear policy questions with Mian and other researchers. During recent summers, the researchers analyzed Pakistan and India's nuclear weapons capabilities, as neither country has disclosed details about its weapons stock.

"This is where the physics comes in. You look at the facilities each country has for making nuclear materials and then try to estimate how many weapons it could make," Mian said. "Some of the information is public, but having the technical expertise helps you know what to look for."

The researchers aimed to raise questions about the Bush administration proposal to lift 30-year-old nuclear trade restrictions on India, which fueled concerns that India could use nuclear material and technologies provided for peaceful purposes to advance its weapons programs, as it did in the 1970s.

The team's analysis concluded, in part, that India could significantly increase its capacity for producing weapons-grade plutonium in the coming years and warned that Pakistan might follow suit. The results have been cited by disarmament and nonproliferation advocates, members of Congress and international leaders. A U.S.-India nuclear cooperation agreement was passed by Congress in October.

M.V. Ramana, an Indian physicist who formerly co-directed the South Asia project with Mian and remains involved with the summer program, said Mian is adept at identifying technical solutions that also have political benefits.

"His concern about nuclear weapons always comes first," said Ramana, who is a fellow with the Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Environment and Development in Bangalore, India. "The scientific methods he employs are simply tools to chip away at the basic issues."

The South Asia project follows the 30 years of research by von Hippel, a theoretical physicist, and Harold Feiveson, a senior research policy analyst in the Wilson School and Program on Science and Global Security. The two men have worked with Soviet scientists, and now Russian and Chinese scientists, to promote disarmament.

"We are using the model that has been practiced at Princeton for many years by people like Frank and Hal, who use their abilities as scholars and scientists to create a new space to practice cooperation," Mian said.

Through the Program on Science and Global Security, Mian also was involved in establishing the International Panel on Fissile Materials. Founded in 2006, the group of independent nuclear experts from 16 countries aims to advance solutions for securing and reducing stocks of highly enriched uranium and separated plutonium -- the key materials for making nuclear weapons.

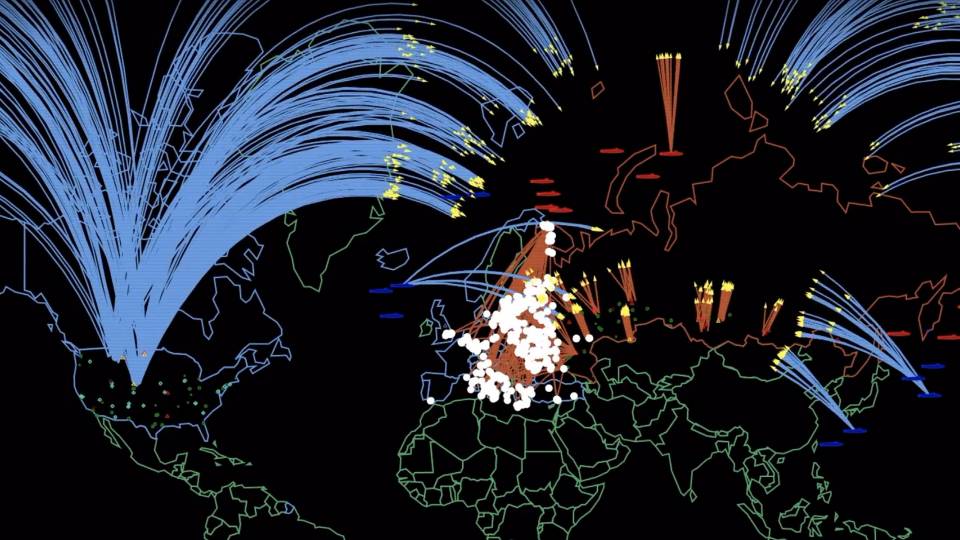

"We have 500 tons of plutonium in the world, and perhaps three times as much highly enriched uranium," Mian said. "That is enough for more than 100,000 nuclear weapons."

The panel recently drafted a treaty to ban the production of highly enriched uranium and plutonium for weapons, and developed ideas for how such a ban might be verified. Mian, von Hippel and Princeton research scholar Alexander Glaser presented the treaty draft to the United Nations in October. Mian said his colleagues on the panel hope the draft will provide the U.N. Conference on Disarmament a template to move forward with its own treaty, for which the process has stalled.

This semester, Mian is teaching the new undergraduate Wilson School course "Special Topics in Public Affairs: Society and Politics in Pakistan," which also is offered as part of the Program in South Asian Studies. Mian's class is presently the only University course devoted to the study of Pakistan. (Photo: Brian Wilson)

Reaching students

Mian also leads courses at Princeton to further students' understanding of nuclear weapons policies and broader issues facing Pakistan and India.

This semester he is teaching the new undergraduate Wilson School course "Special Topics in Public Affairs: Society and Politics in Pakistan," which also is offered as part of the Program in South Asian Studies. Mian's class is presently the only University course devoted to the study of Pakistan.

The course covers Pakistan's history and economy, as well as nuclear weapons, the rise of the Taliban, U.S.-Pakistan relations, environmental issues and the women's movement. Mian and the students are keeping abreast of the country's evolving political situation following the summer resignation of Gen. Pervez Musharraf as president and the election of new president Asif Ali Zardari.

Mian said he hopes students will gain a more nuanced understanding of Pakistan and how societies work in general.

"Pakistan is not just about the Taliban or the war on terror -- it is a country of 160 million people with all kinds of hopes and fears, a complex and dynamic developing society with many significant changes taking place," he said. "The future of Pakistan will be determined by how all of these issues play out."

Senior Jenny Zhang said the class provides historical context to the political and military issues facing Pakistan today.

"Professor Mian has a very strong understanding of history and political events, and is very good at illustrating themes for people who aren't acquainted with India and Pakistan," said Zhang, a politics major. "He also asks scientific questions that are extremely thought-provoking."

In the spring, Mian is scheduled to teach for the second time the freshman seminar "Life in a Nuclear-Armed World." Mian said he is intrigued by how the post-Cold War generation of students views nuclear issues.

Students in last year's seminar analyzed ways the world has been viewed through the lens of the nuclear threat, from films depicting the atomic bomb to an examination of the effects of nuclear weapons programs on the environment, society, democracy and international relations.

Mian recently appeared before the United Nations to present a draft treaty to ban the production of highly enriched uranium and plutonium for nuclear weapons. The treaty was drafted by the International Panel on Fissile Materials, an independent group of nuclear experts affiliated with the Program on Science and Global Security. (Photo: Gudrun Georges)

Activist analyst

Born in a small village in the southern central part of Pakistan, Mian went to school in England. He said he began to think deeply about nuclear issues as an undergraduate at the University of London, from which he graduated in 1982.

"The world was consumed by the tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, and the threat of nuclear war," he said. "Especially studying physics, people would ask you what it meant from a scientific point of view."

At the same time, citizens were grappling with the implications of their countries' nuclear policies.

"I've always tried to balance those two aspects throughout my work: thinking about these issues as a physicist and an ordinary citizen," Mian said.

Mian earned his master's in geophysics and planetary science in 1983 from University of Newcastle Upon Tyne in England and returned to complete his Ph.D. in physics in 1991.

Mian started his career teaching at Quaid-i-Azam University in Islamabad and later worked at the Sustainable Development Policy Institute in Islamabad, an independent environmental think tank. He was a visiting fellow at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies in New Delhi and at the Union of Concerned Scientists in Cambridge, Mass.

As Pakistan and India have built up their nuclear programs, Mian has collaborated with artists and activists as well as scholars to inform the South Asian nuclear debate. Mian and Pervez Hoodbhoy, a physics professor and activist in Islamabad, made two documentaries on peace and security in South Asia that have been shown in international film festivals.

The 2001 documentary "Pakistan and India Under the Nuclear Shadow" was the first Pakistani documentary on the dangers of nuclear weapons.

"In the United States and many other countries, people are familiar with the effects of nuclear weapons through movies, television, novels and even comic books. In countries like Pakistan it's difficult for people to have a picture in their mind about what it means to drop a nuclear bomb because these images are not part of popular culture," Mian said. "We tried to show people through the films what nuclear weapons mean and why it is a mistake to seek nuclear weapons."

The 2004 film "Crossing the Lines: Kashmir, Pakistan, India" focused on the disputed territory of Kashmir and the historical tensions between Pakistan and India.

"The aim of the film was to challenge the national stories common in India, Pakistan and Kashmir and to make a case for living together in plural and diverse democratic societies rather than fighting over borders," Mian said.

Mian said it's heartening that the films continue to be shown and to be well received in both Pakistan and India. But he said there is a lot more work to be done as the arms race in South Asia has shown no sign of slowing.

"Zia continuously and tirelessly uses every available means to educate people about nuclear issues," said his colleague Ramana. "I think the most important point that he repeatedly makes in different ways is that it is not nuclear weapons in South Asia that's the problem, but that nuclear weapons anywhere, whether they are in Islamabad or Moscow or Omaha, are our problem."